Overview

Female urinary system

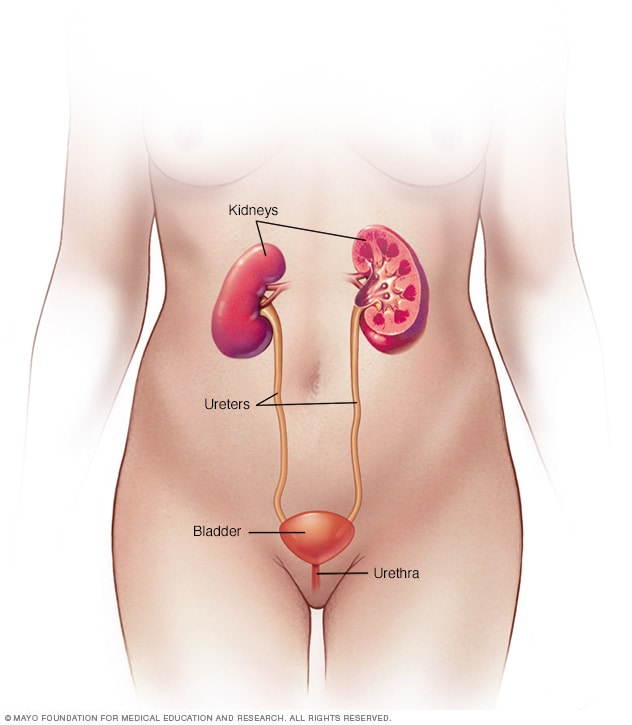

Female urinary system

The urinary system includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. The urinary system removes waste from the body through urine. The kidneys sit toward the back of the upper abdomen. They filter waste and fluid from the blood and make urine. Urine moves from the kidneys to the bladder through narrow tubes called the ureters. The bladder stores urine until it's time to urinate. Urine leaves the body through a small tube called the urethra.

Male urinary system

Male urinary system

The urinary system includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. The urinary system removes waste from the body through urine. The kidneys sit toward the back of the upper abdomen. They filter waste and fluid from the blood and make urine. Urine moves from the kidneys through narrow tubes to the bladder. These tubes are called the ureters. The bladder stores urine until it's time to urinate. Urine leaves the body through a small tube called the urethra.

Vesicoureteral (ves-ih-koe-yoo-REE-tur-ul) reflux means that some urine flows in the wrong direction once it reaches the bladder. It flows back up tubes called ureters that connect the kidneys to the bladder. Typically, urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters down to the bladder. It's not supposed to flow back up.

Most often, vesicoureteral reflux is found in infants and children. Some are born with vesicoureteral reflux due to an issue with the structure of one of the two ureters. Others develop the condition later for reasons such as the bladder not being able to empty fully.

With vesicoureteral reflux, urine can carry germs from the bladder up to the kidneys. That raises the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs). UTIs can happen in any of the organs that make urine and remove it from the body. These infections can cause symptoms such as a strong need to urinate and pain while urinating. Without treatment, UTIs can lead to kidney damage.

Some children who are born with vesicoureteral reflux outgrow it. Others need treatment such as medicine or surgery. The goal of treatment is to prevent kidney damage and more UTIs.

Products & Services

Types

Symptoms

Vesicoureteral reflux symptoms often are due to a urinary tract infection (UTI). A UTI doesn't always cause symptoms, but most people notice some.

These symptoms can include:

- A strong, constant urge to urinate.

- A burning feeling when urinating.

- The need to pass small amounts of urine often.

- Cloudy urine.

- Fever.

- Pain in the side, groin or stomach area.

Babies and some small children with UTIs can't tell adults what their symptoms feel like. But they may have:

- A fever for no clear reason.

- Lack of hunger.

- Fussiness.

As a child gets older, vesicoureteral reflux that doesn't get treated can lead to:

- Bed-wetting.

- Constipation or loss of control over bowel movements.

- High blood pressure.

- Protein in urine.

- Urgent need to urinate or urinating more often than usual.

- Leaking urine by accident, also called urinary incontinence.

Another symptom of vesicoureteral reflux is swelling of one or both kidneys. This swelling is called hydronephrosis. It's caused by the backup of urine into the kidneys. An imaging test called an ultrasound often finds this swelling before a baby is born.

When to see a doctor

Call a healthcare professional right away if your child has any UTI symptoms, such as:

- A strong, persistent urge to urinate.

- A burning sensation when urinating.

- Pain in the stomach area, groin or side.

- Upset stomach or vomiting.

Call your healthcare professional about fever if your child:

- Is younger than 3 months old and has a rectal temperature of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) or higher. A child 2 months old or younger may need emergency care.

- Is 3 months or older and has a fever of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) or higher without other symptoms that lasts more than 24 hours.

- Is also eating poorly, has had major changes in mood, or looks or acts very sick.

Causes

There are two main types of vesicoureteral reflux, and they have different causes.

-

Primary vesicoureteral reflux. Children are born with this more common type of reflux. It's caused by a problem with the valve that usually keeps urine from flowing backward from the bladder. The valve doesn't close well. This lets urine flow back up tubes called ureters that carry urine from the kidneys down to the bladder.

As children grow, the ureters lengthen and straighten. That may help the valve work better and correct the backflow of urine over time. This type of vesicoureteral reflux tends to run in families. So it may be genetic. But the exact cause isn't known.

- Secondary vesicoureteral reflux. This type of reflux most often happens because the bladder doesn't empty properly. There can be many reasons for this. For example, a fold of tissue may block urine from fully leaving the bladder. Or muscles that connect the bladder to another tube called the urethra may become too narrow. Or the nerves that control the bladder's ability to empty may become damaged.

Risk factors

Risk factors for vesicoureteral reflux include:

- Bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD). Children with BBD hold their urine and stool. They also get repeated urinary tract infections. That can contribute to vesicoureteral reflux.

- Race. White children appear to have a higher risk of vesicoureteral reflux than do Black children.

- Sex assigned at birth. In general, girls have a much higher risk of having this condition than boys do. The exception is for vesicoureteral reflux that's present at birth. This is more common in boys.

- Age. Infants and children up to age 2 are more likely to have vesicoureteral reflux than older children are.

- Family history. Primary vesicoureteral reflux tends to run in families. Children whose parents had the condition are at higher risk of it. Siblings of children who have the condition also are at higher risk. So your healthcare professional may recommend screening tests for siblings of a child with primary vesicoureteral reflux.

Complications

Kidney damage is the main health concern, also called complication, that can happen with vesicoureteral reflux. The worse the reflux, the more serious the complications are likely to be.

Complications may include:

- Kidney scarring. Without treatment, UTIs can lead to lasting damage to kidney tissue known as scarring. Extensive scarring may lead to high blood pressure and kidney failure.

- High blood pressure. The kidneys filter waste from the bloodstream. So damage to the kidneys can cause waste to build up. That in turn can raise blood pressure.

- Kidney problems. Scarring can cause an affected kidney to have trouble filtering blood. This may lead to kidney failure, meaning the kidney loses its filtering ability. This life-threatening condition can happen quickly, also known as acute kidney injury. Or it can develop over time, also called chronic kidney disease.

Feb. 05, 2025