June 11, 2024

In the warmer months, families and friends look forward to gathering around a campfire in the backyard, a park or at a campsite. They enjoy chatting, roasting and eating s'mores, sipping a beverage, and sometimes singing songs with a guitar. For these relaxing and bonding moments, Denise B. Klinkner, M.D., M.Ed., pediatric trauma center director at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, offers trauma professionals some key prevention and treatment tips if a child becomes injured by a campfire. She encourages trauma professionals to spread the word in their communities about campfire risks and injury prevention.

حروق

حروق

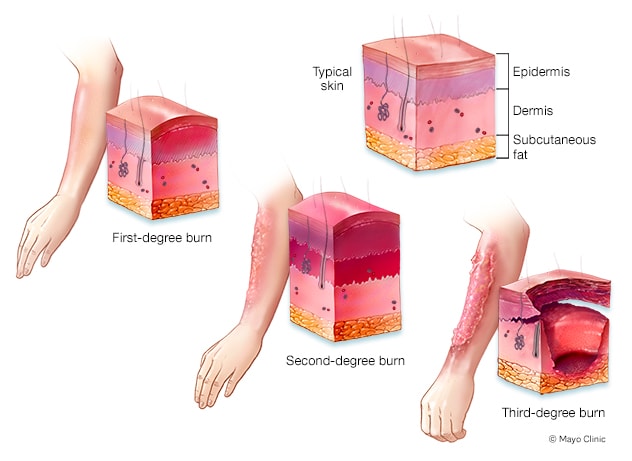

حروق من الدرجة الأولى والثانية والثالثة على الذراع.

Falls into fires are most common, with the palms of the hands most likely to be burned. Campfire burns in children usually are second degree and at times third degree.

Points to consider with lighting a campfire

When lighting a campfire, it is important that those in your community are aware of the risks and enjoy the fire with caution, says Dr. Klinkner.

She notes that common campfire dangers for children include:

- Propane. A firepit with this fuel runs the risk of an explosion.

- Accelerants. If individuals use an accelerant to enhance a fire and the chemical is not well-sealed, Dr. Klinkner says this puts children at risk. If a campfire burns a child and an accelerant is present, the chemical can worsen any burns. This type of burn injury occurs most commonly on children's hands. Caregivers also must be sure these items are sealed to avoid ingestions.

- Grease. This is another substance that intensifies campfires and any burns from them. Typically, grease emanates from food roasting over a campfire, often dripping into the flames as the food cooks.

- Roasting sticks or camp forks. These implements can cause stab wounds or eye injuries.

- Falls. Children can trip and fall around campfires, leading to burn injuries. Toddlers and preschoolers who are still developing their coordination are at higher risk.

For adults, Dr. Klinkner urges vigilance and awareness, especially related to the fire's status and the location of children.

Despite these risks, she does not advocate prohibiting campfires.

"It's almost a part of a life ritual," she says. "But approach it in a diligent manner for a safe environment."

She also says that building or buying a different firepit is not the answer — that risks are similar with all types, providing the owner maintains the firepit. Dr. Klinkner also considers it acceptable to teach a child of a responsible age to build a campfire.

Campfire-related injury treatment

It is crucial to disseminate information to your community about actions to take if a child suffers a campfire burn, says Dr. Klinkner.

If any clothing or body part catches fire, she suggests encouraging community members to use the "stop, drop and roll" fire safety technique to extinguish any flames or smoldering.

If multiple adults are present, she recommends they all help put out the fire, using water or a bucket of sand if the fire is oil- or grease-related.

If a child experiences extensive burns and blisters from a campfire, Dr. Klinkner indicates an adult or responsible young person should apply a clean, dry dressing or plastic wrap around the extremity. This blocks the airflow over the burn, a source of significant pain.

If a child presents at your trauma center with a campfire-related injury, Dr. Klinkner suggests the following steps:

- Assess the trauma ABCs: airway, breathing and circulation.

- Administer pain control as appropriate for the injury.

- Provide supplemental oxygen.

- Resuscitate the child with fluids.

- Determine if the child needs transfer to a burn center.

- Identify appropriate treatment, such as a topical agent or grafting, for the type of burn.

- Maintain tight glycemic control in the child's body. This improves pediatric outcomes for significant burns.

- Verify if the child has an up-to-date tetanus booster. Administer the booster to any children who have not received it in five years.

Mayo Clinic in Minnesota is not a burn center and treats second-degree or splash burns. For more serious burns in children, Mayo Clinic stabilizes the patient and transfers to a burn center. Burn centers use the following transfer criteria, according to the American Burn Association's guidelines listed in UpToDate:

- Partial-thickness burns of greater than 10% of the total body surface area.

- Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum or major joints.

- Third-degree burns in any age group.

- Electrical burns, including lightning injury.

- Chemical burns.

- Inhalation injury.

- Burn injury in patients with preexisting medical disorders that could complicate management, prolong recovery or affect mortality.

- Burns and concomitant trauma — such as fractures — when the burn injury poses the greatest risk of morbidity or mortality. If the trauma poses the greater immediate risk, the patient's condition may be stabilized initially in a trauma center before transfer to a burn center. Physician judgment will be necessary in such situations and should be in concert with the regional medical control plan and triage protocols.

- Children with burns should be transferred to a burn center verified to treat children. In the absence of a regional pediatric burn center, an adult burn center may serve as a second option for the management of pediatric burns.

- Burn injury in patients who will require special social, emotional or rehabilitative intervention.

Dr. Klinkner indicates that medical professionals tend to overestimate the extent of a child's burns. For easy on-the-spot reference, she says the size of the patient's palm is about 1% of body surface area.

Telehealth also can be a useful tool for initial burn assessment and treatment, she says. Dr. Klinkner indicates a discussion with a healthcare professional at Mayo Clinic or a burn center may be helpful, especially with the visuals video provides.

Although patients and families may not be open to discussion about future campfire safety at the time of the injury, Dr. Klinkner believes it is reasonable and appropriate for trauma professionals to gain understanding of how the current injury occurred and determine if it is exceptional or likely to recur.

For more information

Joffe M. Moderate and severe thermal burns in children. UpToDate. 2024.

Refer a patient to Mayo Clinic.