June 12, 2018

A 33-year-old woman presented to an outside facility with increasing shortness of breath, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and increasing lower limb edema — findings suggestive of biventricular heart failure. Further questioning revealed a two- to three-month history of unintentional weight loss, heat intolerance, diarrhea, abdominal pain and palpitations.

The symptoms started about six months after her most recent delivery of a healthy child. Her past medical history was significant for obesity, mild asthma requiring occasional albuterol use and third trimester gestational hypertension during her recent pregnancy (managed without pharmacotherapy).

On presentation, the patient showed signs of tachycardia (118 beats per minute) and tachypnea (22 breaths per minute) and had lower extremity pitting edema. Laboratory testing was significant for hyperthyroidism:

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) < 0.1 mIU/L (normal, 0.49 to 4.67 mIU/L)

- Free thyroxine (FT4) 2.6 ng/dL (normal, 0.7 to 1.8 ng/dL)

The serum brain natriuretic peptide was markedly increased at 2,819 pg/mL (normal < 100 pg/mL). Chest X-ray demonstrated cardiomegaly. The patient was diuresed and started on beta-adrenergic blockade and 10 mg of methimazole three times a day. An echocardiogram demonstrated a severely dilated left ventricle and an ejection fraction of 10 to 15 percent.

Cardiovascular surgery operating room at Mayo Clinic

Cardiovascular surgery operating room at Mayo Clinic

This image from a cardiovascular surgery operating room is representative of the significant amount of equipment and coordinated care required during insertion, adjustment or both of ECMO or to support patients with ECMO who require an operation.

Despite treatment, shortness of breath and hypotension necessitated intra-aortic balloon pump placement and intubation, and she was transferred to Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. On arrival, she was sedated, intubated and hypotensive on inotropic support. A repeat echocardiogram revealed an ejection fraction of 9 percent. Due to severe cardiogenic shock, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) cannulation was initiated.

Endocrinology was consulted. Mild exophthalmos was noted without dermopathy or acropachy. The patient's presentation with decompensated heart failure, preceding gastrointestinal complaints, and tachycardia was highly suggestive of thyroid storm (Burch and Wartofsky Point Scale 40).

Aggressive therapy was started with 200 mg of propylthiouracil administered every four hours, 100 mg of hydrocortisone administered every eight hours and a saturated solution of potassium iodine administered two hours after propylthiouracil. Repeat biochemical testing revealed a TSH of < 0.01 mIU/L (normal, 0.4 to 4.0 mIU/L), FT4 of 3.4 ng/dL (normal, 0.9 to 1.7 ng/dL) and a total tri-iodothyronine of 308 ng/dL (normal, 80 to 200 ng/dL).

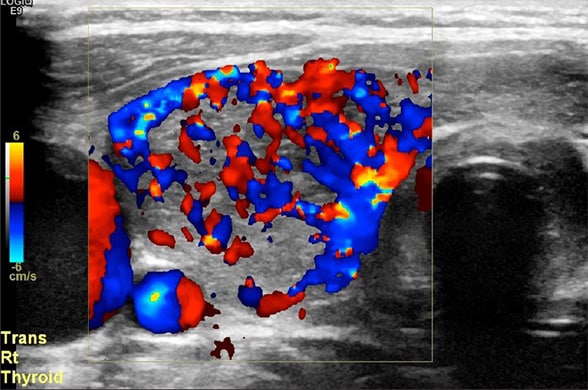

Right midthyroid lobe demonstrating increasing vascularity

Right midthyroid lobe demonstrating increasing vascularity

Doppler ultrasound of right midthyroid lobe demonstrating increasing vascularity.

While thyroid receptor antibodies were pending, a bedside ultrasound revealed a hypervascular thyroid gland. The patient's clinical picture was most consistent with cardiogenic shock in the setting of thyroid storm of autoimmune origin, and possible postpartum cardiomyopathy.

Despite treatment, five days later the patient was still clinically and biochemically hyperthyroid with serum TSH of 0.02 mIU/L and FT4 of 5.4 ng/dL by equilibrium dialysis (employed because of her significantly altered protein status). Given the critical nature of the patient's condition and the need for rapid normalization of her thyroid status, total thyroidectomy was recommended.

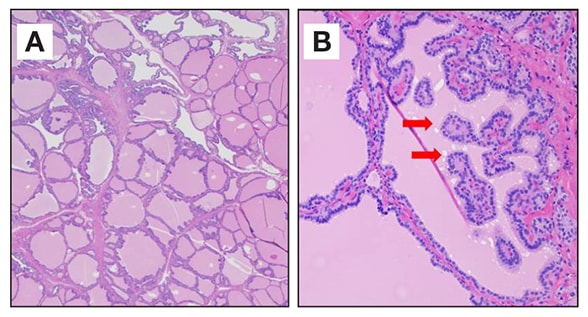

Microscopic magnification of thyroid tissue

Microscopic magnification of thyroid tissue

Low (A) and high (B) microscopic magnification of thyroid tissue demonstrating epithelial hypertrophy and invagination forming papillary projections and scalloping of colloid (red arrows) consistent with Graves' disease.

Plasmapheresis was initiated to optimize preoperative thyroid levels. Endocrine and cardiovascular surgeons collaborated to perform a total thyroidectomy during which anticoagulation, necessary for ECMO, was held. Pathology revealed diffuse follicular hyperplasia consistent with Graves' disease. As expected, the patient also had an elevated thyroid receptor antibody concentration of 20 IU/L (normal, 0 to 1.75 IU/L).

Postoperatively, anticoagulation was restarted without complication.

Following total thyroidectomy, the patient improved and was able to be weaned off vasopressor support and she was extubated. Thyroid replacement therapy was initiated. Unfortunately, her cardiac function remained suboptimal (ejection fraction of 15 percent), and therefore a left ventricular assist device was placed to bridge to cardiac transplantation.

As highlighted in an article in the journal Thyroid in 2012, thyroid storm is a life-threatening condition and early recognition is essential — mortality remains high (11 percent) despite improvements in management. The diagnosis should be considered in an individual with severe symptoms of multiorgan dysfunction and biochemical thyrotoxicosis. Several scoring systems have been devised to assist recognition and early implementation of aggressive treatment. The authors note that a high level of suspicion is important.

In this case, despite aggressive nonsurgical management of hyperthyroidism, additional cardiovascular support was required. ECMO can be used in such cases, and a growing body of literature supports its use in thyroid storm-induced cardiogenic shock refractory to usual treatment — as highlighted in an article in the journal Thyroid in 2011.

Total thyroidectomy for thyroid storm on ECMO, however, has not been reported, but occurred without complication in this case. Close collaboration between endocrinology, endocrine surgery and cardiovascular surgery is vital. Reports suggest that rapid cardiac function recovery with the normalization of thyroid hormone occur following thyroidectomy. In the current case, cardiac function improved, but left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapy was eventually required to bridge to cardiac transplantation, suggesting an additional underlying cardiomyopathy. The patient was able to be discharged home with an LVAD, awaiting heart transplantation.

Key points

- Early recognition and appropriate treatment of thyroid storm — which may include thyroidectomy — is essential to improve outcome.

- Thyroidectomy should be pursued when medical therapy fails to control the thyrotoxicosis.

- ECMO should be considered as a means of cardiac support in patients who are unresponsive to conventional therapy until thyroid hormone normalization can be achieved.

For more information

Akamizu T, et al. Diagnostic criteria, clinical features, and incidence of thyroid storm based on nationwide surveys. Thyroid. 2012;22:661.

Hsu LM, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation rescues thyrotoxicosis-related circulatory collapse. Thyroid. 2011;21:439.