Feb. 27, 2018

Diagnosis and management of small bowel (SB) bleeding remains a challenging problem faced by gastroenterologists, both from a clinical and financial standpoint. The increasing age of the patient population, associated comorbidities, and the use of newer anticoagulants and cardiac support devices, including left ventricular assist devices, have added further complexity to SB bleeding management.

While advances in endoscopic and radiologic testing have enabled gastroenterologists to successfully navigate difficult SB anatomy, detect mucosal lesions and perform therapy, several important issues require consideration. These include:

- Appropriate selection of patients for evaluation

- Optimal selection and timing of tests

- Understanding when a conservative approach might be more cost-effective

In an article published in Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology in 2016, Shabana F. Pasha, M.D., and Jonathan A. Leighton, M.D., gastroenterologists at Mayo Clinic's campus in Arizona, present an overview of small bowel bleeding to guide decision-making in the management of this disorder.

What are causes of SB bleeding?

NSAID-related diaphragm in the distal ileum

NSAID-related diaphragm in the distal ileum

NSAID-related diaphragm in the distal ileum seen on balloon-assisted enteroscopy.

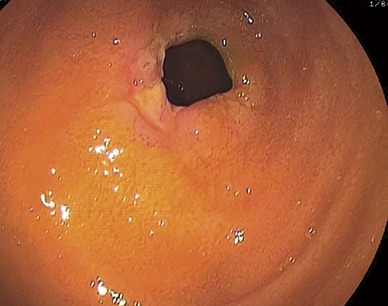

Ulcerated mass lesion in the jejunum

Ulcerated mass lesion in the jejunum

Ulcerated mass lesion in the jejunum seen on balloon-assisted enteroscopy.

Small bowel angioectasia in the proximal small bowel

Small bowel angioectasia in the proximal small bowel

Small bowel angioectasia in the proximal small bowel seen on capsule endoscopy.

The majority of patients with SB bleeding have angioectasias, while other common lesions include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-related enteropathy (NSAID-related diaphragm), Crohn's disease and small bowel tumors.

"It's important to recognize that the prevalence of SB lesions differs according to age and ethnicity of patients," says Dr. Pasha. "Vascular lesions are more common in older patients, especially those with cardiac and renal comorbidities, while younger patients are more likely to have underlying Crohn's disease, Meckel's diverticula and SB tumors. Vascular lesions are also the most common cause of SB bleeding in the United States and Europe, while inflammation and tumors are more common in Asia.

"This knowledge may be helpful for clinicians to select the most appropriate test(s) to optimize diagnostic and therapeutic yield, and adopt a more cost-effective approach to management."

Who needs evaluation?

Typically, SB endoscopy is pursued in patients with persistent or recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding after a negative bidirectional endoscopy, and in those with unexplained iron deficiency anemia regardless of the results of a fecal occult blood test. It should also be considered in select situations of a first episode of bleeding, especially in younger patients, due to a higher likelihood of SB tumors, and in those who present with severe bleeding.

Diagnostic testing

A variety of endoscopic and radiologic tests are available to evaluate the small bowel for bleeding. "Understanding the advantages and limitations of these tests, as well as their diagnostic yield and therapeutic capabilities, can help clinicians determine the most appropriate choice for a given patient," says Dr. Pasha.

Capsule endoscopy

Capsule endoscopy (CE) is superior to other diagnostic tests for detection of clinically significant SB findings, making it the first test of choice in the majority of patients with SB bleeding. It provides detailed imaging of the small bowel mucosa, and superior detection of multiple vascular lesions, inflammation and tumors.

However, the test may miss solitary lesions, including SB tumors. Another risk is CE retention, which occurs in up to 1.5 percent of patients with SB bleeding, and may require endoscopic management or surgery for retrieval. Patients with NSAID enteropathy, Crohn's disease, SB tumors, radiation enteritis and prior SB surgery are at increased risk of retention.

"In patients with concern for capsule retention, a patency capsule can be completed prior to the capsule endoscopy to assess for SB patency," says Stephanie L. Hansel, M.D., M.S., a gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic's campus in Minnesota.

The yield of CE is dependent upon timing of the test relative to the bleeding episode. The highest likelihood of detecting treatable SB lesions is when CE is performed within 72 hours of bleeding. The yield significantly declines two weeks after the bleeding episode.

Multiphase CT scan (angiography and enterography)

Multiphase CT enterography (CTE) has a higher sensitivity than capsule endoscopy for the detection of small bowel tumors. The administration of a large volume of neutral or negative oral contrast allows adequate SB distension and evaluation of mucosal details, while IV contrast allows optimal visualization of the mesenteric vasculature.

CT angiography (CTA) without oral contrast is recommended for urgent imaging in patients with active bleeding, especially those with hemodynamic instability. With its rapid imaging capabilities and higher accuracy, CTA has largely replaced the technetium 99m red blood cell scan. Multiphase CT imaging is contraindicated in patients with decreased renal function and IV contrast allergy.

Therapeutic modalities

Deep enteroscopy (DE):

- The primary role of DE is for treatment of SB lesions detected on diagnostic testing. The available DE techniques — balloon-assisted (double-balloon enteroscopy and single-balloon enteroscopy) and spiral enteroscopy — have a comparable diagnostic and therapeutic yield in SB bleeding.

- DE may also be useful for diagnosis of SB bleeding in select patients after negative noninvasive testing, and in patients with postsurgical altered SB anatomy. Similar to CE, the closer that DE is performed to the bleeding episode, the higher the yield of the test.

- DE should be reserved for patients with a high likelihood of SB lesions, as the procedures are relatively invasive, require anesthesia and additional personnel, and are typically longer in duration than standard endoscopy. Adverse events include cardiopulmonary complications, bleeding, ileus, perforation and, rarely, pancreatitis.

Mesenteric angiography:

- Reserved for therapeutic management of patients with severe GI bleeding, mesenteric angiography allows performance of urgent angiographic embolization, especially in those with hemodynamic instability. Embolization procedures can have high rates of serious adverse events, including bowel infarction, which may increase with repeat embolizations.

Intraoperative endoscopy (IOE):

- IOE is now reserved for management of refractory bleeding and known SB lesions (including tumors and NSAID-related diaphragms), and when endoscopic and radiologic tests are unsuccessful in detecting and treating the underlying source of bleeding.

Patient outcomes

Long-term patient outcomes associated with SB bleeding, especially after endoscopic treatment of vascular lesions, are still unknown. Although the recurrence rate of SB bleeding is high, endoscopic treatment typically reduces transfusion requirements. Pharmacological management with octreotide and somatostatin analogues, and thalidomide, has a limited role in SB bleeding.

"At Mayo Clinic, we have experts in capsule endoscopy, multiphase CT imaging, angiography, balloon-assisted enteroscopy and intraoperative enteroscopy. Our expertise and close collaboration of different specialties, including gastroenterology, radiology, cardiology, surgery and others, allows us to offer a multidisciplinary and individualized approach toward management of our patients with small bowel bleeding," says Dr. Pasha.

For more information

Pasha SF, et al. Detection of suspected small bowel bleeding: Challenges and controversies. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2016;10:1235.