May 08, 2024

Gut microbiome derangement, also known as dysbiosis, is common in the ICU, potentially leading to a heightened risk of nosocomial infections, organ failure, septic shock and mortality. A recent study published in BMC Medicine assessed the safety, feasibility and impact of kefir administration on the gut microbiome of adults who are critically ill in the ICU setting.

With the frequency of gut microbiome derangement, many standard therapeutic interventions are pursued such as antibiotics, gastric acid suppression agents, opioids, antipsychotics, certain parenteral and enteral nutritional preparations, laxatives, and corticosteroids. These interventions may not only deplete the commensal gut flora but also pave the way for pathogenic bacteria to thrive.

Enhancing the gut microbiome has been proposed as a strategic approach to mitigate potential adverse outcomes. "While prior research on select probiotic supplements has not successfully shown to improve gut microbial diversity, fermented foods offer a promising alternative," says Lioudmila V. Karnatovskaia, M.D., an author of this study and a pulmonologist and critical care specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. "In this open-label phase 1 safety and feasibility study, we examined the safety and feasibility of kefir as an initial step towards utilizing fermented foods to mitigate gut dysbiosis in critically ill patients."

Between July 2022 and February 2023, the health records of 722 patients in the ICU were reviewed. Of those, 54 patients with intact gastrointestinal tracts were enrolled in the study. These patients had an average age of 64.6 years and a mean body mass index of 34.9, with a predominance of white ethnicity (98%). Of the 54 patients, 87% of them received multiple antibiotic treatments (with anaerobic coverage in 78%) during their ICU stay. Kefir was administered in escalating doses, starting with 60 mL and followed by 120 mL after 12 hours, then 240 mL daily. To evaluate kefir's safety, gastrointestinal symptoms were monitored.

Feasibility was determined by whether the patients received a minimum of 75% of their assigned kefir doses. To assess changes in the gut microbiome composition following kefir administration, researchers collected two stool samples from 13 patients: one within 72 hours of admission to the ICU (T1) and another at least 72 hours after the first stool sample (T2).

After receiving kefir, none of the 54 patients in the study exhibited symptoms of kefir-related bacteremia. Despite challenges such as taste preferences leading to the introduction of flavored kefir, the study found kefir administration to be feasible and safe, with no severe adverse effects linked to its consumption. The primary safety concern was diarrhea in two patients, which could not be conclusively attributed to kefir due to concurrent laxative use and the commonality of diarrhea in the ICU setting.

Out of the 393 kefir doses prescribed for all patients in the study, 359 (91%) were successfully administered. Initial stool samples were collected from 29 (54%) patients and a follow-up sample from 13 (24%) patients. Analysis of the 26 paired samples revealed no increase in gut microbial α-diversity between the two timepoints. Stool samples collected before and after kefir administration showed significant changes in the gut microbiome of patients who were critically ill. Despite administering antibiotics, which likely influenced these changes, analysis revealed a decrease in microbial diversity.

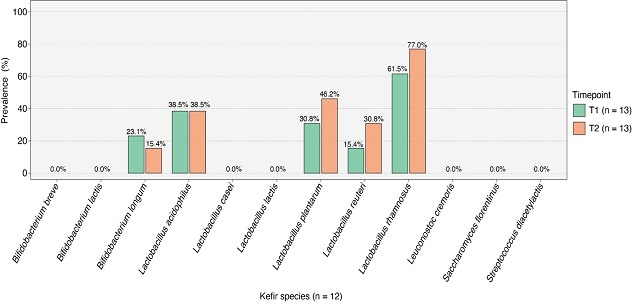

Prevalencia de especies microbianas

Prevalencia de especies microbianas

Se observa una presencia variable de especies microbianas específicas asociadas al kéfir en los intestinos de los pacientes. Gráfico reimpreso de BMC Medicine.

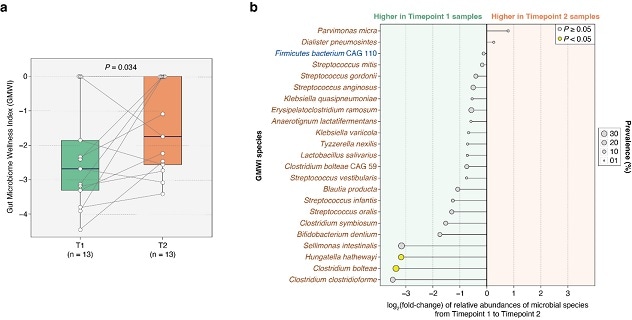

Índice de bienestar del microbioma intestinal

Índice de bienestar del microbioma intestinal

Este gráfico muestra que la administración de kéfir puede mejorar la salud intestinal de pacientes gravemente enfermos. Gráfico reimpreso de la revista BMC Medicine.

However, specific microbial species associated with kefir showed varying presence in the patients' guts, indicating potential engraftment.

There was a significant improvement in the Gut Microbiome Wellness Index (GMWI) score by the second timepoint (P = 0.034, one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). This finding supports the hypothesis that kefir administration can improve gut health in patients who are critically ill. The chart represents the fold-change in relative abundances of GMWI species between T1 and T2, with the names of health-prevalent species depicted in blue (n = 1) and those of health-scarce species depicted in brown (n = 22).

Providing kefir to patients who are critically ill appears to be safe and feasible. "Our findings warrant a larger evaluation of kefir's safety, tolerability and impact on gut microbiome dysbiosis in patients admitted to the ICU. An observed improvement in the GMWI suggests potential health benefits," says Dr. Karnatovskaia. "Future work would refine kefir dosing, enhance sample collection and incorporate control groups to more effectively evaluate kefir's benefits on gut health and patient outcomes in the ICU."

For more information

Gupta VK, et al. Safety, feasibility, and impact on the gut microbiome of kefir administration in critically ill adults. BMC Medicine. 2024;22:80.

Refer a patient to Mayo Clinic.