Dec. 21, 2019

Mayo Clinic combines the latest technology with a holistic approach for the optimal management of epilepsy. Sophisticated imaging and surgical techniques, and a multidisciplinary focus encompassing psychosocial problems associated with epilepsy, are the cornerstones of this patient-centered care.

"Epilepsy is more than just having seizures. There are significant comorbidities associated with it, particularly depression and anxiety. We understand that, and truly consider the whole picture for each patient," says Joseph I. Sirven, M.D., a neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Phoenix/Scottsdale, Arizona.

Psychiatrists and neuropsychologists are involved in the diagnostic process and the consideration of treatment options. "Patients need a lot of support to get through these diagnostic procedures and through surgery, if that's done. In our pre-surgical conference, we always discuss the psychosocial situation for the patient and the family, and what the best options might be for this patient," says Richard S. Zimmerman, M.D., a neurosurgeon at Mayo Clinic's campus in Arizona.

The technology available at all Mayo Clinic campuses for managing epilepsy includes:

- High-density electroencephalography (EEG)

- Subtraction ictal single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) coregistered to MRI (SISCOM)

- Stereo electroencephalography (stereo EEG)

- Surgery performed in the MRI suite

- Laser interstitial thermal therapy for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy

- Neuromodulation, including responsive neurostimulation

Having that range of technology allows Mayo Clinic to meet the complex needs of patients.

"These technologies all test the brain in different ways — structure, electrical activity, blood flow and metabolism. It's best not to rely on one of these tests alone," says Amy Z. Crepeau, M.D., a neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Arizona. "We can use a number of these imaging options together to determine where seizures originate when someone has uncontrolled epilepsy."

Pinpointing seizure origin sites

High-density EEG uses as many as 256 electrodes to noninvasively capture seizure activity. "The abnormal surges in brain activity during a seizure — and often, even when a seizure is not happening — are small and can be difficult to pick up. High-density EEG can record smaller changes involving smaller areas of the brain. That gives us additional information that a routine EEG might miss," Dr. Crepeau says.

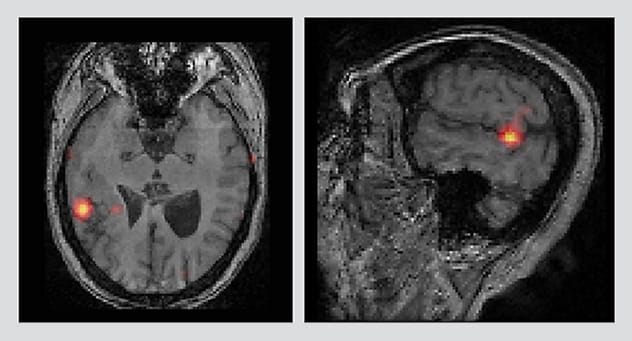

Las imágenes de la SISCOM muestran el inicio de las convulsiones

Las imágenes de la SISCOM muestran el inicio de las convulsiones

La sustracción axial y sagital de la tomografía computarizada por emisión de fotón único ictal corregistrada con imágenes por resonancia magnética (SISCOM) muestra la ubicación del inicio de las convulsiones.

SISCOM developed by Mayo Clinic and used clinically since 2003, is an additional tool for localizing seizure origins. SISCOM provides precise measurement of blood flow during a seizure. Testing is performed in the epilepsy monitoring unit. When a seizure starts, a specially trained nurse immediately injects a tracer, and the patient is given a SPECT scan.

A second SPECT scan is performed when the patient isn't having a seizure — typically, about 24 hours after the first scan. Radiologists perform a subtraction analysis that highlights how blood flow differs during a seizure versus at rest. These images are then superimposed on the patient's MRI to allow the epilepsy neurologist and the neurosurgeon to identify where seizures originate.

Ubicación de los electrodos implantados de estereoelectroencefalograma

Ubicación de los electrodos implantados de estereoelectroencefalograma

Una reconstrucción tridimensional del cerebro muestra la ubicación de los electrodos implantados de estereoelectroencefalografía (estereoelectroencefalograma). Cada punto azul representa un contacto de electrodo. Los puntos rojos muestran la activación de los contactos de los electrodos cuando comienza una convulsión.

If noninvasive tests don't provide sufficient information, stereo EEG might be used. This procedure combines MRI and intraoperative neural navigation to map seizures originating in deeper brain areas.

"We may have some idea of where the seizure originates, based on what the seizure does to the patient — for example, hand jerks," Dr. Zimmerman says. "Computers that link the patient's anatomy in real time to his or her MRI allow us to place as many as 20 very narrow electrodes into specific areas of the brain to localize seizure origin. Craniotomy isn't required. We can cover large areas of the brain by inserting wires into extremely small holes."

After the electrodes are placed, seizures are recorded over several days to determine where they start. "Although it is always preferable to get all of the information we need without any invasive testing, sometimes noninvasive tests are just not enough. Stereo EEG is a minimally invasive option," Dr. Crepeau says.

Once seizure origin sites are identified, Mayo Clinic has a range of treatment options. Treatment can be performed in the MRI suite, providing continuous monitoring of the brain throughout the procedure.

MRI-guided laser interstitial thermal therapy might be used to ablate seizure origin locations. The minimally invasive procedure provides real-time feedback on the tissue being ablated. "That allows us to maximize the removal of seizure-generating tissue while avoiding damage to eloquent tissue," Dr. Zimmerman says.

Neuromodulation, using an implanted device that stimulates the brain to stop seizures, can be an option for patients who aren't suitable candidates for surgical resection or laser ablation. Constant stimulation can be provided in a specific brain area; alternatively, deep brain stimulation provides constant, nonspecific stimulation.

Mayo Clinic also uses responsive neurostimulation devices, which continuously monitor brain activity and discharge stimulation as needed to stop a seizure when it occurs. As a lead participant in the approval process for responsive neurostimulation devices, Mayo Clinic has extensive experience with this treatment.

"These devices provide long-term recording of the patient's brain activity. That allows us to change the level of stimulation or even to change a patient's medication based on data, as opposed to relying on the patient's memory of seizures," Dr. Zimmerman says.

Chronic subthreshold stimulation of the cortex, which acts earlier than conventional neurostimulation devices to prevent seizure onset, is another treatment pioneered at Mayo. The levels of electrical stimulation used in subthreshold cortical stimulation are low enough to stop seizure initiation without causing loss of function in that part of the brain.

Research is underway at Mayo Clinic to improve the protocols for neuromodulation devices. Mayo Clinic researchers are also working to find new EEG biomarkers for better anatomical location of seizure origins.

"Research is a key aspect of our approach to clinical practice," Dr. Sirven says. "All of our efforts focus on improving outcomes, both surgical and psychosocial, in these very complex patients."