March 18, 2025

The computational method used by U.S. hospitals to measure perinatal care adjusts for maternal health factors when considering nulliparous, term, singleton and vertex cesarean delivery (NTSV-CD) rates. However, The Joint Commission's perinatal care ratings for these hospitals do not account for maternal or fetal health factors.

"Most OB-GYNs will mention the lack of risk adjustment when looking at OB quality of care assessed by The Joint Commission," says Leslie Carranza, M.D., an obstetrician at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who is her department's quality chair. "C-section rates are huge in OB rankings."

She indicates the maternity outcomes measurements The Joint Commission uses are simplistic and were developed in the early 2000s. Dr. Carranza says that today, figures are risk adjusted for all other public quality measures.

"We can build more sophisticated models for quality outcomes for our OB patients," she says.

The Joint Commission owns The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, which published this study's findings.

"The editors saw value in this paper and were complimentary," says Dr. Carranza. "We were pleasantly surprised."

Mayo Clinic's study and its findings

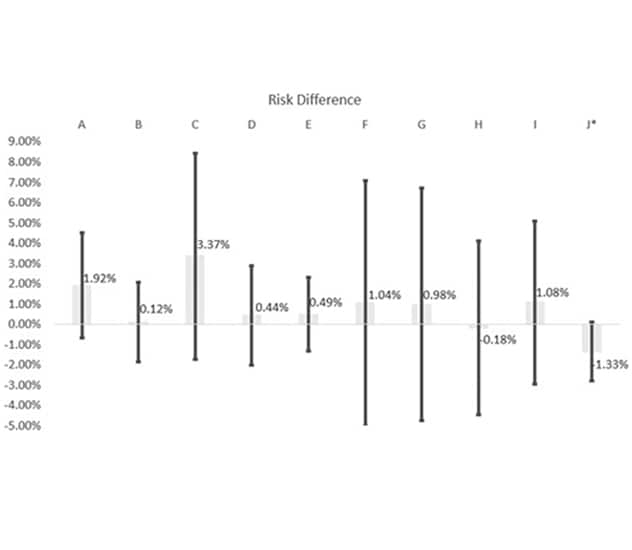

同一医疗系统中 10 家医院的医院特定风险差异,对比经风险调整与未经调整的 NTSV-CD 率。

同一医疗系统中 10 家医院的医院特定风险差异,对比经风险调整与未经调整的 NTSV-CD 率。

本图显示了我们医疗系统中 10 家医院(医院 A 至 J)的医院特定风险差异(95% 置信区间 [CI]),将经风险调整的初产妇足月单胎头位剖宫产率(NTSV-CD)与未经调整的 NTSV-CD 率进行比较。带标签的灰色条柱表示风险差异的幅度(例如,医院 C 为 3.37%,表示经风险调整的剖宫产率是 30.18%,未经调整的剖宫产率是 26.81%),黑线则显示 95% CI。

*医院 J 的 p < 0.10 具有边缘显著性;其他所有医院均为 p > 0.10。

Dr. Carranza and colleagues had concerns about these conflicting computational methods and their effects on hospital quality ratings. Therefore, they undertook a study to test risk adjustment by adding maternal risk factors when determining hospital-level NTSV-CD rates at 10 hospitals in one health system.

This study determined that risk adjustment for age, diabetes and hypertensive disorders — prior to or during pregnancy — and obesity is achievable. Not only that, Dr. Carranza and colleagues found this adjustment significantly affected hospitals' NTSV-CD rates and, therefore, would meaningfully change The Joint Commission's ratings for hospitals assigned a borderline perinatal care rating.

"In our study, when we took these four factors into account, three hospitals' rankings changed," says Dr. Carranza, noting all these considerations relate to the patient, rather than the fetus. "We witnessed that two high-performing hospitals lost their perinatal care high performance, and one low-performing hospital became high-performing."

Because of The Joint Commission's nonadjusted C-section rates for perinatal care quality measurement, Dr. Carranza's key concern for pregnant patients is that they will shortchange themselves by selecting a hospital for delivery based on nonadjusted quality measures. For hospitals, one of her major concerns is that their quality scores based on no adjustment can completely misalign with the rest of a hospital's care ratings.

"There's a shocking disparity between women's maternity outcomes and other health quality outcomes," she says.

Mayo Clinic in Minnesota's OB practice and C-section

Hospitals have little control over their pregnant patient populations, the composition of which can impact perinatal care ratings without adjustment, says Dr. Carranza. For instance, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, only about 30% of the pregnant patients are considered NTSV, which influences overall quality ratings.

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, not only serves local pregnant patients but also is a referral center for patients at higher risk during pregnancy. These patients often have more serious or complex pregnancy conditions leading to higher complication rates, says Dr. Carranza. She also notes that some patients who live across the country choose to fly to Minnesota to deliver at Mayo Clinic.

Dr. Carranza indicates that her department has worked diligently to reduce C-section rates, stating: "Vaginal delivery is always best for the patient and the baby if we can do that safely."

As a C-section is a surgical procedure, she also notes that it presents risks such as bleeding, structural damage and infant breathing problems, though the latter typically is transient.

A question of safety plus obstetrician and patient autonomy

Dr. Carranza contends that failing to account for a patient's health factors when deciding between a vaginal or C-section delivery is unsafe. It also removes the obstetricians' right to determine the delivery method they feel is best for the patient, she notes.

"This is not fair criteria for perinatal care quality," she says. "Not using risk-adjusted quality measures does not give credit to obstetricians' decision-making. Sometimes a C-section is not a medical failure when labor is contraindicated."

She notes that often when an OB opts for a C-section in consult with the patient, the decision relates to an obstructed labor or evidence of fetal labor intolerance. Dr. Carranza says that, for example, placenta previa is an absolute vaginal birth contraindication, as the patient and baby have significant mortality risks.

"With placenta previa, attempting a vaginal delivery can lead to a devastating outcome," says Dr. Carranza.

She notes it was not until 2024 that The Joint Commission recognized this condition as a vaginal delivery contraindication.

According to Dr. Carranza, decision-making about the best delivery method is not always straightforward and can require significant training and experience.

"It's not as simple as a vaginal birth is appropriate for first-time parents where the baby is in the right position in the pelvis," she says. "It's a more nuanced decision, especially in high-risk pregnancies."

"What we think is right is not the ultimate determinant of how delivery should proceed: It's how patients and their families want to have their babies."

Dr. Carranza also believes patients should determine their preferred delivery methods.

"We respect bodily autonomy and how patients want to birth their children," she says. "If we believe in the principle of patient autonomy and the patient wants a primary C-section, we must honor that. We can't refuse a C-section request, just like a patient's request for minimal interventions during labor. What we think is right is not the ultimate determinant of how delivery should proceed: It's how patients and their families want to have their babies."

The typical C-section rate for babies she delivers is 18% to 33%, a rate significantly impacted by patient pregnancy complexity levels.

Risk adjustment, however, leads to appropriate accountability for quality perinatal care, according to Dr. Carranza.

"Without risk adjustment, accountability is in the wrong things," she says. "An example is a small hospital with low-risk patients which has a higher-than-expected C-section rate. Another example is a large hospital with sicker patients where vaginal birth is not an option without compromising the patient and the baby."

Future areas for improvement in perinatal care assessment

Dr. Carranza also advocates for race and ethnicity adjustments for perinatal patient care assessment.

Hospitals do not always treat diverse groups of patients well during their perinatal care, says Dr. Carranza.

"So, a movement toward equity and respect is a needed one," Dr. Carranza says. "Patients in these populations need to have their wishes for their deliveries respected."

Dr. Carranza also suggests that future perinatal care quality ratings should adjust for race and ethnicity. Data on experiences during prenatal care, labor and postpartum care from diverse groups of patients should be publicly available to the patients and their families, she says.

Fetal health also could be a key future component in determining perinatal care quality and a likely next step in creating a more comprehensive risk-adjusted quality measure, says Dr. Carranza.

For more information

Pollock PD, et al. A simple risk adjustment for hospital-level nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rates and Its implications for public reporting. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2024;50:500.

Refer a patient to Mayo Clinic.