Dec. 31, 2020

Dennis W. Dickson, M.D., and Pamela J. McLean, Ph.D., discuss Lewy body dementia and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiative aimed at better understanding the disease. Dr. Dickson directs the Brain Bank for Neurodegenerative Disorders at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida. Dr. McLean directs the Neurobiology of Parkinson's Disease Laboratory at Mayo Clinic's campus in Florida. Together they co-direct a team of international investigators in the multiyear, multimillion-dollar NIH initiative.

What challenges does Lewy body dementia pose for patients and clinicians?

Lewy body dementia is a progressive, incurable disease that causes severe physical and cognitive decline. Although it's the second most common dementia after Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body dementia is underdiagnosed and can be definitively identified only postmortem. Death occurs on average about eight years after the start of clinical manifestations.

脑内 α-突触核蛋白聚集体(路易体)

脑内 α-突触核蛋白聚集体(路易体)

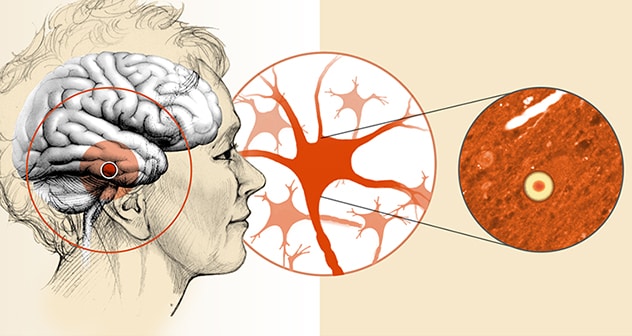

路易体痴呆症的特征是在脑部的几个区域检测到神经细胞内蛋白质聚集体。

Those manifestations vary widely among patients. In addition to cognitive problems, they include motor problems such as parkinsonism, sleep disorders — especially dream-enactment behavior — and problems with autonomic control. Postmortem brain analysis finds aggregates of alpha-synuclein known as Lewy bodies within neurons, as well as variable deposits of beta-amyloid protein, a key feature of Alzheimer's disease.

Thus, Lewy body dementia has components of both Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease, and a great deal of overlap with the symptoms and pathologies of other dementias. It is important to make the correct diagnosis because patients who experience delusions and hallucinations might be prescribed first-generation antipsychotic medications, which can worsen Lewy body dementia symptoms and even be life-threatening.

What does the NIH hope to accomplish through the Lewy body dementia initiative?

The goal is to learn more about the proteins involved in Lewy body dementia so we can characterize disease progression and identify potential therapeutic targets. We don't yet understand what individual roles alpha-synuclein and beta-amyloid might play in Lewy body dementia or if there are synergistic interactions between those two proteins.

This initiative is a multidisciplinary project that follows the NIH's Center Without Walls model, in which several institutions collaborate to achieve a single high-priority goal. We expect to generate a great deal of data, which will be shared with academic institutions and pharmaceutical companies interested in drug discovery. No single institution has all the answers, especially in a disease as complex as Lewy body dementia.

What specific efforts are planned?

We will start by analyzing Lewy body dementia tissue samples in the brain bank on Mayo Clinic's campus in Florida. The brain bank contains more than 8,000 specimens, including nearly 1,000 brains donated by people with Lewy body dementia. Through those analyses we hope to confirm and characterize the pathology of Lewy body dementia, and choose samples from the most severely affected individuals to discover the molecular underpinnings of the disorder.

We will then distribute the samples to our Mayo colleagues and the collaborating institutions for further analysis. Those centers will gather genetic and genomic information and look for changes in proteomics, lipids and RNA. Since all the samples originate from a single laboratory, we're able to cut down on the variability that poses a problem when samples come from different locations. The goal is to obtain complementary information on all the major macromolecules in the brain.

In addition to alpha-synuclein and beta-amyloid, tau is found in some Lewy body dementia donor brains. Those individuals unfortunately had both Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body dementia. We hope our studies can address whether these dementias are discrete disorders or a single entity that exists on a disease spectrum.

How will the effects of Lewy bodies on brain mechanisms be explored?

The effects of alpha-synuclein and beta-amyloid species from the donor brains will be tested on patient-derived neurons grown in petri dishes in Mayo's Neurobiology of Parkinson's Disease and Translational Cell Biology of Parkinson's Disease laboratories. We want to decipher the cellular dysfunction these protein species promote and determine which species are most toxic. Understanding what these proteins are doing to the cells will give us new targets for therapeutics.

What other Mayo Clinic researchers and institutions are involved in the NIH initiative?

Our Mayo Clinic colleagues include Guojun Bu, Ph.D., Owen A. Ross, Ph.D., and Wolfdieter Springer, Ph.D., at the Florida campus, and John D. Fryer, Ph.D., at the Arizona campus. The participating institutions are University College London, Columbia University, University of Arizona, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital and University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

What other efforts are underway at Mayo Clinic to learn more about Lewy body dementia?

Dr. Dickson's team has additional projects, supported by the Harry T. Mangurian Jr. Foundation, focusing on the interface between normal aging and Lewy body dementia. With funding from an NIH U01 grant, Mayo Clinic neuroradiologist Kejal Kantarci, M.D., and colleagues are working to apply advanced imaging technology to detect the progression of Lewy body dementia and to discover biomarkers for the disease. Bradley F. Boeve, M.D., leads Mayo's Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence, as well as conducts research on sleep disorders in Lewy body dementia, including experimental therapeutic trials.

Mayo Clinic has a long history of Lewy body dementia research and clinical studies, in addition to providing clinical care and support for people with the disease.

For more information

Neurobiology of Parkinson's Disease Laboratory. Mayo Clinic.