May 19, 2023

Pectus excavatum is a condition in which the breastbone is sunken into the chest. It is quite common — affecting 1 in 1,000 people. While the sunken breastbone is often noticeable in infancy, the severity of pectus excavatum typically worsens during growth spurts, particularly during adolescence.

Once diagnosed, children with this condition should have an initial evaluation around the age of 10 to 12. Symptoms may include the appearance of the pectus, shortness of breath and exercise intolerance. If the pectus is severe, patients might experience rapid heartbeat or palpitations, wheezing, and chest pain. Due to the potential complications that can arise, early and consistent monitoring is important. Pediatric surgeons at Mayo Clinic Children's Center have the necessary resources and testing capabilities to ensure each child is properly monitored for heart and lung complications and assessed for surgical intervention as needed.

"The best time to do the surgery is ages 12 to 14," says D. Dean Potter Jr., M.D., chair of Pediatric Surgery at Mayo Clinic's campus in Minnesota. "Younger children generally don't yet have the maturity to go through this procedure. By the time children are skeletally mature, their chest walls are a little more rigid. While that's not necessarily a problem for successful surgery, it may make the procedure more painful."

To minimize radiation exposure, Mayo Clinic Children's Center uses X-rays rather than CT scans to obtain the chest-cage measurements needed to plan surgery. Pulmonary function tests are done to exclude asthma or other pulmonary conditions as a cause of symptoms. Echocardiography may be performed to assess heart function. Additional monitoring and care is provided for children whose pectus excavatum is associated with a connective tissue disorder, such as Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Enhanced pain management for pectus excavatum surgery

Pectus excavatum surgery

Pectus excavatum surgery

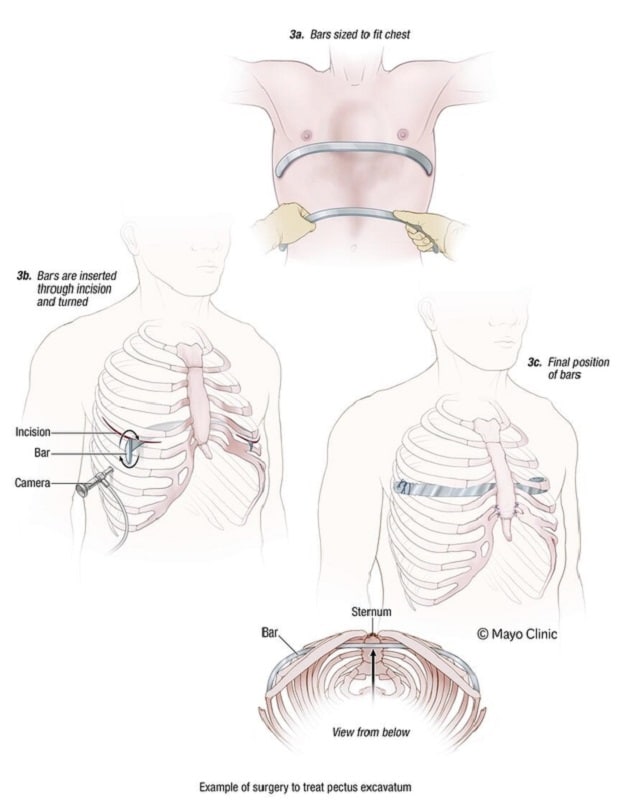

This is an example of a surgical procedure to treat pectus excavatum.

The two most common surgical procedures to repair pectus excavatum are known by the names of the surgeons who first developed them:

- Nuss procedure. This minimally invasive procedure uses small incisions placed on each side of the chest. Long-handled tools and a narrow fiber-optic camera are inserted through the incisions. A curved metal bar is threaded under the depressed breastbone, to raise it into a more typical position. In some cases, more than one bar is used. The bars are removed after two or three years.

- Ravitch technique. This older procedure involves a much larger incision down the center of the chest. The surgeon removes the affected cartilage attaching the ribs to the lower breastbone and then fixes the breastbone into a more normal position with surgical hardware, such as a metal strut or mesh supports. These supports are removed after 12 months.

Mayo Clinic Children's Center uses a multidisciplinary approach to manage pain after pectus excavatum surgery, typically leading to decreased use of pain medications, improved pain scores and shorter hospital stays. The approach, developed by Mayo Clinic pediatric surgeons and anesthesiologists, involves several options including a cryotherapy procedure that temporarily numbs the nerves on both sides of the chest and the insertion of paravertebral catheters that pump a local anesthetic to the intercostal nerves for about a week after surgery.

Patients generally can resume all activities three months after surgery. If they have had cryotherapy for postoperative pain control, sensation typically returns within four months.

"Since we started a multimodal pain management strategy in 2010, the use of opioids has gone down by more than half while pain scores have dropped significantly, which means children are having less pain. With this strategy, children are getting out of bed sooner and drinking and eating much earlier than before," says Dawit T. Haile, M.D., chair of Pediatric Anesthesiology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. "One option is the use of paravertebral catheters, in which we use ultrasound to insert nerve catheters to block nerves innervating the chest wall while the patient is asleep. This avoids the pain and anxiety of placing the catheters while the patient is awake, such as when an epidural is placed."

According to Dr. Potter, this enhanced pain management has helped reduce the average length of hospital stay to 2 to 3 days. "Pain medication can be infused in the hospital and for 2 to 3 days after patients leave. The catheters are removed at home. It's as easy as removing a dressing," he says.

Pre-op

Pre-op

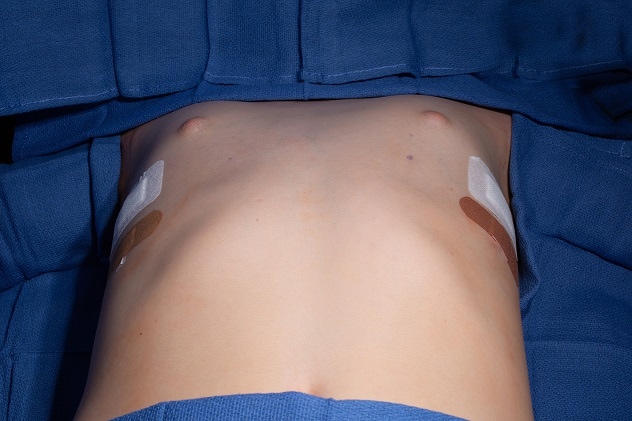

This photo shows the chest of a child before pectus excavatum surgery.

Post-op

Post-op

This photo shows the chest of the same child after pectus excavatum surgery.

"Another option to reduce postoperative pain is cryotherapy, which speeds up our patients' overall recovery," says Denise B. Klinkner, M.D., M.Ed., a pediatric surgeon at Mayo Clinic in Rochester. "Cryotherapy temporarily numbs the nerves on both sides of the chest, often until the pain from surgery has subsided. Because of this innovative approach, we have further reduced the typical hospital stay to one night, and the majority of our patients leave the hospital with a reduced need for opioid pain medication."

Hundreds of minimally invasive pectus surgeries have been done at Mayo Clinic Children's Center since it became one of the first centers in the United States to offer the procedure. Dr. Potter notes that patients and their parents consistently report high satisfaction with the outcomes.

"We see kids who couldn't run a mile and all of a sudden become runners after recovering from surgery," Dr. Potter says. "Other children who were a bit embarrassed by their appearance come out of their shells and get involved in activities. These kids are much happier."

For more information

Refer a patient to Mayo Clinic.