June 12, 2018

One of the adverse effects related to opioid use is opioid-induced bowel dysfunction (OIBD). OIBD is characterized by a broad range of disordered gastric, small bowel and colonic motility. The most commonly reported symptom associated with OIBD is constipation. Upper gastrointestinal signs and symptoms associated with OIBD include nausea, vomiting, reflux and dyspepsia, while lower gastrointestinal symptoms include bloating, abdominal cramps and spasm.

Previous research has established that activation of any of the three peripheral opioid receptors can affect motility, blood flow, secretion and absorption within the GI tract. These changes then alter gastric, small bowel and colon function. The effect of opioids on esophageal motility is less clear. This condition, known as opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction (OIED), is the subject of multiple studies conducted by Mayo Clinic researchers.

In a study published in The American Journal of Gastroenterology in 2015, Mayo Clinic researchers and colleagues sought to shed light on how opioids affect esophageal function.

Methods

This retrospective study identified 121 chronic opioid users who underwent esophageal pressure topography (EPT) testing. Researchers divided the 121 study subjects into two groups and examined the impact of opioid use on esophageal motility using the Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders version 3.0. One group of 66 individuals was taking opioids at the time of the EPT, and the second group of 55 individuals discontinued opioid medication use at least 24 hours before the EPT.

Results

Esophagogastric junction (EGJ) outflow obstruction was significantly more prevalent in subjects using opioids during testing compared with those who discontinued their use 24 hours before testing (27 percent versus 7 percent, P = 0.004).

Achalasia type III (characterized outflow obstruction along with spastic contractions) was significantly more prevalent in subjects using opioids during testing compared with those who discontinued their use 24 hours before testing (11 percent versus 0 percent, P = 0.01).

Distal esophageal spasm (DES) and Jackhammer esophagus (JE, a form of hypercontractile peristalsis) were more common in patients evaluated on opiates, but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

"Our findings confirmed that opioid use is associated with esophageal dysfunction, explains Michael D. Crowell, Ph.D., one of the article's co-authors. Dr. Crowell is a researcher at Mayo Clinic's campus in Arizona who focuses on the evaluation and treatment of gut motility disorders. "Opioid use within 24 hours of manometry was associated with increased esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction and other spastic esophageal abnormalities."

The research team members say that they don't believe that selection bias played a role, as they observed manometric differences between the two groups even though similar proportions of subjects from each group presented with dysphagia. "Our data suggest that manometric patterns typical of type III achalasia and esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction should be interpreted with caution in patients currently taking opioids," said Dr. Crowell.

The research team acknowledged that the exact mechanism of opioid-induced esophageal dysmotility remains unclear. "One theory is that opiates may interfere with inhibition of contractions by preferentially acting on nitric oxide-releasing neurons rather than cholinergic neurons, causing unopposed excitatory input, therefore leading to impaired relaxation and spastic contractions," said Dr. Crowell.

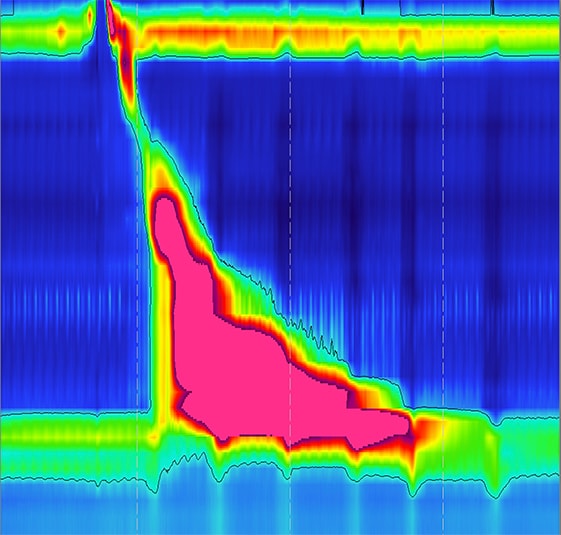

High-resolution manometry showing achalasia type III in an opiate user

High-resolution manometry showing achalasia type III in an opiate user

High-resolution manometry showing achalasia type III in an opiate user. This subtype of achalasia is characterized by impaired EGJ relaxation and spastic, high-amplitude contractions in the esophageal body.

Researchers based at Mayo Clinic's campus in Arizona conducted an additional study in 2018 that examined whether opioid type and dosing have a measurable impact on OIED in patients undergoing high-resolution manometry (HRM). In that study, OIED was defined by the presence of DES, EGJ outflow obstruction, type III achalasia or JE on HRM, using the Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders version 3.0.

Methods

The team conducted a retrospective review of 274 chronic opioid users who completed HRM between 2012 and 2017. This analysis included 225 patients taking oxycodone, hydrocodone or tramadol, and 49 patients taking other opioids in numbers too small for meaningful analysis. Researchers extracted demographic and manometric data from an esophageal motility database. They then calculated a total 24-hour opioid dosing of respective opioid type and converted it to a morphine-equivalent dose for analysis.

Results

- OIED was significantly more prevalent among subjects using oxycodone or hydrocodone, compared with those using tramadol (31 percent versus 28 percent versus 12 percent, P = 0.0162).

- OIED was more prevalent among subjects using oxycodone alone, compared with subjects using oxycodone with acetaminophen (43 percent versus 21 percent, P = 0.0482).

- There was no difference in OIED for subjects taking hydrocodone alone versus hydrocodone with acetaminophen.

- Subjects with OIED were taking a significantly higher mean 24-hour dose of opioids than those without OIED (95 mg versus 50 mg, P = 0.0293).

Conclusions

"Our results suggest that OIED is more prevalent in patients taking oxycodone or hydrocodone when compared with those taking tramadol," says Marcelo F. Vela, M.D. Dr. Vela, the study's lead author, is a gastroenterologist specializing in GERD and esophageal motility disorders, and the director of the Esophageal Interest Group at Mayo Clinic's campus in Arizona.

"We also observed that concomitant use of acetaminophen reduced the likelihood of OIED in patients taking oxycodone, but not in those taking hydrocodone. And there appears to be a dose effect, meaning that stronger doses of opioids are associated with a higher likelihood of OIED. These results suggest that reducing opioid dose or prescribing tramadol, instead of hydrocodone or oxycodone, may help reduce OIED in opioid users," says Dr. Vela.

Two additional studies conducted by Mayo researchers and published in 2010 and 2016 also yielded interesting findings that focused on opioid use and esophageal motility. The 2010 article showed a range of manometric abnormalities induced by opiates in patients with dysphagia. The results published in 2016 demonstrated that chronic opiate use was common among patients diagnosed with type III achalasia and may therefore be causative.

"These findings suggest the existence of a physiologic mechanism for opiate-induced type III achalasia and a need for further studies to clarify the association between opiate use and achalasia," says Karthik Ravi, M.D., lead author of the 2016 article about achalasia and a gastroenterologist specializing in esophageal disorders at Mayo Clinic's campus in Minnesota.

For more information

Ratuapli SK, et al. Opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction (OIED) in patients on chronic opioids. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;110:979.

Opiate-induced oesophageal dysmotility. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2010;31:601.

Ravi K, et al. Achalasia and chronic opiate use: Innocent bystanders or associated conditions? Diseases of the Esophagus. 2016;29:15.