Overview

Small bowel prolapse (enterocele)

Small bowel prolapse (enterocele)

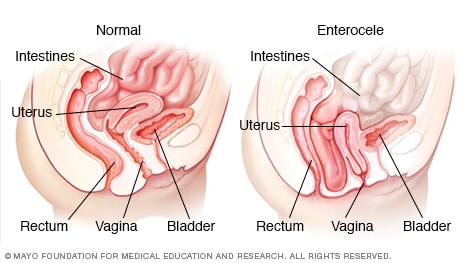

Small bowel prolapse (enterocele) occurs when muscles and tissues that hold the intestines (small bowel) in place inside the pelvic cavity weaken, causing the small bowel to descend and bulge into the vagina.

Small bowel prolapse, also called enterocele (EN-tur-o-seel), occurs when the small intestine (small bowel) descends into the lower pelvic cavity and pushes at the top part of the vagina, creating a bulge. The word "prolapse" means to slip or fall out of place.

Childbirth, aging and other processes that put pressure on your pelvic floor may weaken the muscles and ligaments that support pelvic organs, making small bowel prolapse more likely to occur.

To manage small bowel prolapse, self-care measures and other nonsurgical options are often effective. In severe cases, you may need surgery to fix the prolapse.

Symptoms

Mild small bowel prolapse may produce no signs or symptoms. However, if you have significant prolapse, you might experience:

- A pulling sensation in your pelvis that eases when you lie down

- A feeling of pelvic fullness, pressure or pain

- Low back pain that eases when you lie down

- A soft bulge of tissue in your vagina

- Vaginal discomfort and painful intercourse (dyspareunia)

Many women with small bowel prolapse also experience prolapse of other pelvic organs, such as the bladder, uterus or rectum.

When to see a doctor

See your doctor if you develop signs or symptoms of prolapse that bother you.

Causes

Increased pressure on the pelvic floor is the main reason for any form of pelvic organ prolapse. Conditions and activities that can cause or contribute to small bowel prolapse or other types of prolapse include:

- Pregnancy and childbirth

- Chronic constipation or straining with bowel movements

- Chronic cough or bronchitis

- Repeated heavy lifting

- Being overweight or obese

Pregnancy and childbirth

Pregnancy and childbirth are the most common causes of pelvic organ prolapse. The muscles, ligaments and fascia that hold and support your vagina stretch and weaken during pregnancy, labor and delivery.

Not everyone who has had a baby develops pelvic organ prolapse. Some women have very strong supporting muscles, ligaments and fascia in the pelvis and never have a problem. It's also possible for a woman who's never had a baby to develop pelvic organ prolapse.

Risk factors

Factors that increase your risk of developing small bowel prolapse include:

- Pregnancy and childbirth. Vaginal delivery of one or more children contributes to the weakening of your pelvic floor support structures, increasing your risk of prolapse. The more pregnancies you have, the greater your risk of developing any type of pelvic organ prolapse. Women who have only cesarean deliveries are less likely to develop prolapse.

- Age. Small bowel prolapse and other types of pelvic organ prolapse occur more often with increasing age. As you get older, you tend to lose muscle mass and muscle strength — in your pelvic muscles as well as other muscles.

- Pelvic surgery. Removal of your uterus (hysterectomy) or surgical procedures to treat incontinence may increase your risk of developing small bowel prolapse.

- Increased abdominal pressure. Being overweight increases pressure inside your abdomen, which increases your risk of developing small bowel prolapse. Other factors that increase pressure include ongoing (chronic) cough and straining during bowel movements.

- Smoking. Smoking is associated with developing prolapse because smokers frequently cough, increasing abdominal pressure.

- Race. For unknown reasons, Hispanic and white women are at higher risk of developing pelvic organ prolapse.

- Connective tissue disorders. You may be genetically prone to prolapse due to weaker connective tissues in your pelvic area, making you naturally more susceptible to small bowel prolapse and other types of pelvic organ prolapse.

Prevention

You may be able to lower your chances of small bowel prolapse with these strategies:

- Maintain a healthy weight. If you're overweight, losing some weight can decrease the pressure inside your abdomen.

- Prevent constipation. Eat high-fiber foods, drink plenty of fluids and exercise regularly to help prevent having to strain during bowel movements.

- Treat a chronic cough. Constant coughing increases abdominal pressure. See your doctor to ask about treatment if you have an ongoing (chronic) cough.

- Quit smoking. Smoking contributes to chronic coughing.

- Avoid heavy lifting. Lifting heavy objects increases abdominal pressure.

Feb. 10, 2023