Diagnosis

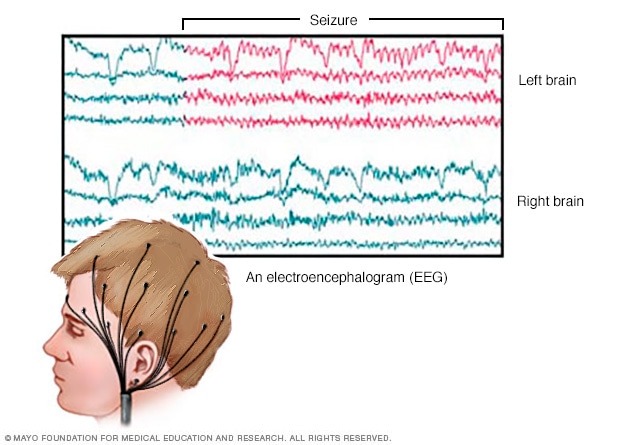

EEG brain activity

EEG brain activity

An EEG records the electrical activity of the brain via electrodes affixed to the scalp. EEG results show changes in brain activity that may be useful in diagnosing brain conditions, especially epilepsy and other conditions that cause seizures.

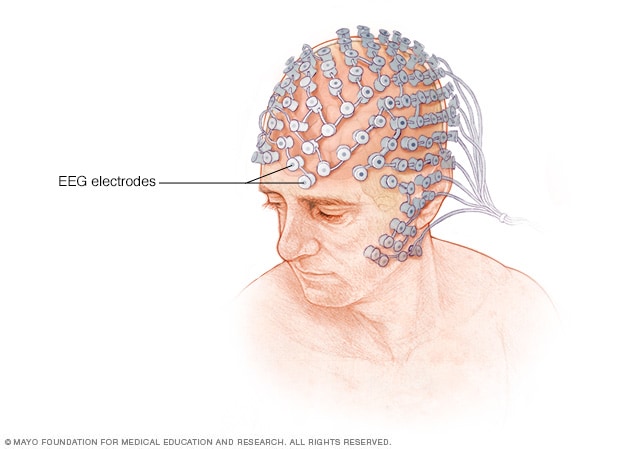

High-density EEG

High-density EEG

During a high-density EEG test, flat metal discs called electrodes are attached to the scalp. In a high-density EEG, shown here, the electrodes are close together. The electrodes are connected to the EEG machine with wires. Some people wear an elastic cap fitted with electrodes instead of having the adhesive applied to their scalps.

CT scanner

CT scanner

A CT scan can see nearly all parts of the body and is used to diagnose disease or injury as well as to plan medical, surgical or radiation treatment.

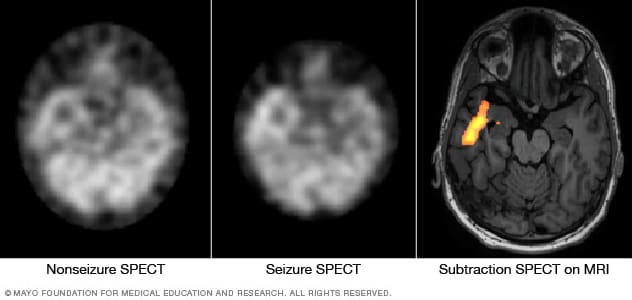

Pinpointing seizure location

Pinpointing seizure location

These SPECT images show the blood flow in the brain of a person when there's no seizure activity (left) and during a seizure (middle). The subtraction SPECT coregistered to MRI (right) helps pinpoint the area of seizure activity by overlapping the SPECT results with brain MRI results.

After a seizure, a health care professional thoroughly reviews your symptoms and medical history. You may need several tests to determine the cause of your seizure and evaluate how likely it is that you'll have another one.

Tests may include:

- A neurological exam. A health care professional may evaluate your behavior, motor abilities and mental function.

- Blood tests. You may need to give a blood sample to check your blood sugar levels and look for signs of infections or genetic conditions. You also may have the levels of salts in your body checked. These salts are known as electrolytes and control the balance of fluids.

- Lumbar puncture, known as a spinal tap. If an infection is suspected as the cause of a seizure, you may need to have a sample of cerebrospinal fluid removed for testing.

An electroencephalogram (EEG). In this test, electrodes attached to your scalp record the electrical activity of your brain. The electrical activity shows up as wavy lines on an EEG recording. The EEG may reveal a pattern that tells whether a seizure is likely to occur again.

EEG testing also may help exclude other conditions that mimic epilepsy. Depending on the details of your seizures, this test may be done at a clinic, overnight at home or over a few nights in the hospital.

Imaging tests may include:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI scan uses powerful magnets and radio waves to create a detailed view of your brain. An MRI may show changes in the brain that could lead to seizures.

- Computerized tomography (CT). A CT scan uses X-rays to obtain cross-sectional images of your brain. CT scans can reveal changes in your brain that might cause a seizure. Those changes may include tumors, bleeding and cysts.

- Positron emission tomography (PET). A PET scan uses a small amount of low-dose radioactive material that's injected into a vein. The material helps reveal active areas of the brain and detect changes.

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). A SPECT test uses a small amount of low-dose radioactive material that's injected into a vein. The test creates a detailed 3D map of the blood flow in your brain that happens during a seizure.

A health care professional also may conduct a type of SPECT test called subtraction ictal SPECT coregistered to MRI (SISCOM). The test may provide even more-detailed results. This test is usually done in a hospital with overnight EEG recording.

An MRI is a very useful tool for helping your doctors see images of the inside of your body, including tissue that can't be seen on a conventional x-ray.

Before your exam, it's very important to fill out the safety screening form carefully. MRI is safe and painless. But metal in the scanner can cause serious safety problems or reduce the quality of the images.

Your health care team needs to know about any metal in your body, even a small shard of metal from an accident. Fillings, bridges, and other dental work typically do not pose a problem. But other metal that has been put into your body might prevent you from having an MRI. That includes some pacemakers, clips for treating aneurysms, and other devices with metal in them.

A nurse may review your health history before your exam. You may be given medications or contrast dye or have blood drawn. Be sure to tell the nurse if you're pregnant, have an allergy to contrast dye, or have kidney or liver problems. You may not wear clothing with snaps or zippers in the scanner. You will be asked to wear a gown. Do not wear any jewelry or bring anything metal into the scanner, including a hearing aid.

An MRI machine uses a powerful magnet to make images of your body. Unlike a CT scan, it does not use x-rays or other radiation. You will be given earplugs. The scanner makes a loud noise when it's operating.

A device called a coil may be put on or around the area to be scanned to help capture the images. You will also be given a squeeze ball to hold. You can use this to signal the technologist any time you need something. The MRI is controlled from a nearby room. You will be closely observed throughout the procedure.

A series of scans are taken with a brief pause between each. You may hear different noises as different scans are taken. It's normal for the noise to be very loud. You need to remain still when the scan is being taken.

People are typically in the scanner from 30 to 50 minutes, depending on the images to be taken. A complex examination can take longer. If you are concerned about being in the scanner for this length of time, talk to your physician and the technologist. They can help you with some tips for staying comfortable.

If you need to be removed from the scanner, this can be done very quickly. The ends of the scanner are always open.

After your exam, the images will be reviewed by your radiologist. He or she will send a report to the health care provider who ordered the test. Ask your health care provider any questions you have about your MRI.

More Information

Treatment

Vagus nerve stimulation

Vagus nerve stimulation

In vagus nerve stimulation, an implanted pulse generator and lead wire stimulate the vagus nerve, which leads to stabilization of irregular electrical activity in the brain.

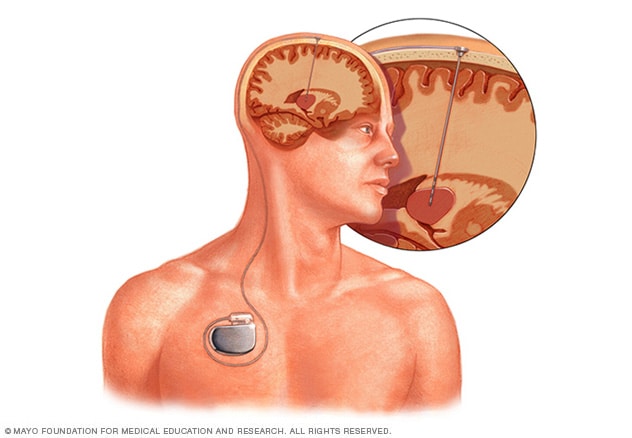

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation involves implanting an electrode deep within the brain. The amount of stimulation delivered by the electrode is controlled by a pacemaker-like device placed under the skin in the chest. A wire that travels under the skin connects the device to the electrode.

Not everyone who has one seizure will have another one. Because a seizure can be an isolated incident, you may not need to start treatment unless you've had more than one.

The optimal goal in seizure treatment is to find the best possible therapy to stop seizures, with the fewest side effects.

Medications

Treatment of seizures often involves the use of anti-seizure medicines. There are many different options for anti-seizure medicines. Most people with epilepsy will stop having seizures after trying just one or two medicines.

The goal of medicine is to find what works best for you and causes the fewest side effects. Sometimes a health care professional might recommend more than one medicine.

Finding the right medicine and dosage can be complex. You may need to try several different medicines. Common side effects may include weight changes, dizziness, fatigue and mood changes. Very rarely, more-serious side effects can cause damage to the liver or bone marrow.

A health care professional considers your condition, how often you have seizures, your age and other factors when choosing which medicine to prescribe. The care professional also will review any other medicines you may be taking to ensure that the anti-seizure medicines won't interact with them.

Dietary therapy

Following a ketogenic diet can improve seizure control. A ketogenic diet is high in fat and very low in carbohydrates. But it can be challenging to follow because there's a limited range of foods allowed.

Variations on a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet also may be helpful but less effective. They include low glycemic index and Atkins diets. These modified diets are still being studied.

Surgery

If treatment with at least two anti-seizure medicines isn't effective, surgery may be an option. The goal of surgery is to stop seizures from happening. Surgery works best for people who have seizures that always begin in the same place in the brain. There are several types of surgery, including:

- Lobectomy. Surgeons locate and remove the area of your brain where seizures begin.

- Thermal ablation, also called laser interstitial thermal therapy. This less invasive procedure focuses highly concentrated energy at a specific target in the brain where seizures begin. This destroys the brain cells that cause seizures.

- Multiple subpial transection. This type of surgery involves making several cuts in areas of the brain to prevent seizures. It's usually done when the area of the brain where seizures start can't be safely removed.

- Corpus callosotomy. This surgery cuts the network of connections between the neurons of the right and left halves of the brain. This is used to treat seizures that start in one half of the brain and travel to the other half. However, even after surgery, seizures may still occur on the side of the brain where they started.

- Hemispherotomy. This surgery completely disconnects one side of the brain from the rest of the brain and body. This type of surgery is only used when medicines aren't effective in managing seizures and when seizures affect only half the brain. Many daily functional abilities may be lost after this surgery. But children can often recover those abilities with rehabilitation.

Electrical stimulation

If the area of the brain where seizures start is unable to be removed or disconnected, devices that provide electrical stimulation may help. They can reduce seizures along with continued anti-seizure medicine use. Stimulation devices that may offer seizure relief include:

- Vagus nerve stimulation. A device implanted underneath the skin of the chest stimulates the vagus nerve in the neck, sending signals to the brain that inhibit seizures.

- Responsive neurostimulation. A device is implanted on the surface of the brain or within brain tissue. The device can detect seizure activity and deliver electrical stimulation to stop the seizure.

- Deep brain stimulation. Surgeons implant thin wires called electrodes within certain areas of the brain to produce electrical impulses. The impulses regulate the brain activity that causes seizures. The electrodes attach to a pacemaker-like device placed under the skin of the chest. This controls the amount of stimulation produced.

Pregnancy and seizures

Women who've had seizures typically are able to have healthy pregnancies. But birth defects related to certain medicines can sometimes occur.

In particular, valproic acid — a medicine for generalized seizures — has been associated with cognitive deficits and neural tube defects, such as spina bifida, in babies. The American Academy of Neurology recommends that women don't use valproic acid during pregnancy because of risks to their babies.

Discuss these risks with your health care team. Creating a plan with your health care team before you become pregnant is particularly important. In addition to the risk of birth defects, pregnancy can alter your medicine levels.

In some cases, it may be appropriate to change the dose of seizure medicine before or during pregnancy. The goal is to be on the lowest dose of the safest seizure medicine that is effective for seizure control.

Taking folic acid before pregnancy may help prevent some complications related to taking anti-seizure medicines while pregnant. Folic acid is found in standard prenatal vitamins. It's recommended that all people of childbearing age take folic acid while on anti-seizure medicines.

Birth control and anti-seizure medicines

Some anti-seizure medicines can alter the effectiveness of birth control. Ask your health care professional if your medicine may interact with your birth control. Other forms of birth control may need to be considered.

You see, an epileptic seizure is an abnormal electrical disturbance of the brain. The device is implanted under the skin, and four electrodes are attached to the outer layers of your brain. The device monitors brain waves, and when it senses abnormal electrical activity it fires electrical stimulation and stops the seizures.

Potential future treatments

Researchers are studying other potential therapies to treat seizures. They include therapies to stimulate the vagus nerve, other cranial nerves or the brain without surgery.

One area of research showing promise is MRI-guided focused ultrasound. The therapy involves pointing ultrasound beams, which are sound waves, to an area of the brain that's causing the seizures. The beam creates acoustic energy to destroy brain tissue in a targeted way without surgery. This type of therapy can reach deeper brain structures. It also can focus on a target without damaging the nearby tissue.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Here are some steps you can take to help with seizure control:

- Take medicine correctly. Don't adjust the dosage before talking to your health care professional. If you feel that your medicine should be changed, talk about it with your care professional.

- Get enough sleep. Lack of sleep can trigger seizures. Be sure to get adequate rest every night.

- Wear a medical alert bracelet. This will help emergency personnel know how to treat you correctly if you have another seizure.

- Be active. Exercising and being active may help keep you physically healthy and reduce depression. Make sure to drink enough water and rest if you get tired during exercise.

- Make healthy life choices. Managing stress, limiting alcohol and not smoking all factor into a healthy lifestyle.

Personal safety

Seizures don't usually result in serious injury, but if you have recurrent seizures, injury is a possibility. These steps can help you avoid injury during a seizure:

- Take care near water. Don't swim alone or ride in a boat without someone nearby.

- Wear a helmet for protection during activities such as bike riding or sports participation.

- Take showers instead of baths unless someone is near you.

- Modify your furnishings. Pad sharp corners, buy furniture with rounded edges and choose chairs that have arms to keep you from falling off of them. Consider carpet with thick padding to protect you if you do fall.

- Display seizure first-aid tips in a place where people can easily see them. Include any important phone numbers.

- Consider a seizure detection device. The Food and Drug Administration has cleared a watch-like prescription device that can detect tonic-clonic seizures (Embrace2). The device alerts loved ones or caregivers so that they can check on you and ensure your safety. Talk with your health care professional to decide if using this type of device might be appropriate for you.

Seizure first aid

It's helpful to know what to do if you witness someone having a seizure. If you're at risk of having seizures in the future, pass this information along to family, friends and co-workers so that they know what to do if you have a seizure.

To help someone during a seizure, take these steps:

- Carefully roll the person onto one side.

- Place something soft under the person's head.

- Loosen tight neckwear.

- Don't put your fingers or other objects in the person's mouth.

- Don't try to restrain someone having a seizure.

- Clear away dangerous objects if the person is moving.

- Stay with the person until medical help arrives.

- Observe the person closely so that you can provide details on what happened.

- Time the seizure.

- Stay calm.

Coping and support

Stress due to living with a seizure disorder can affect your mental health. It's important to talk with your health care provider about your feelings and seek ways you can find help.

At home

Your family members can provide much-needed support. Tell them what you know about your seizures. Let them know they can ask you questions, and be open to conversations about their worries. Help them understand your condition by sharing educational materials or other resources that your health care professional has given you.

At work

Meet with your supervisor and talk about your seizures and how they affect you. Discuss what you need from your supervisor or co-workers if a seizure happens while at work. Consider talking with your co-workers about seizures. This will help widen your support system and bring about acceptance and understanding.

You're not alone

Remember, you don't have to go it alone. Reach out to family and friends. Ask your health care professional about local support groups or join an online support community. Don't be afraid to ask for help. Having a strong support system is important to living with any medical condition.

Preparing for your appointment

Sometimes seizures need immediate medical attention, and there's not always time to prepare for an appointment.

Other times, your first appointment to evaluate a seizure may be with your health care professional. Or you may be referred to a specialist. You might see a specialist trained in brain and nervous system conditions, known as a neurologist. Or you might be referred to a neurologist trained in epilepsy, known as an epileptologist.

To prepare for your appointment, consider what you can do to get ready. Also understand what to expect.

What you can do

- Record information about the seizure. Include the time, location, symptoms you experienced and how long it lasted, if you know these details. Seek input from anyone who may have seen the seizure, such as a family member, friend or co-worker. They might provide information you may not know.

- Be aware of any pre-appointment restrictions. At the time you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance to be ready for any medical tests or exams.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins or supplements that you're taking, including dosages.

- Take a family member or friend along to help you remember all the information provided during an appointment. Because you may not be aware of everything that happens when you're having a seizure, someone who was a witness can provide helpful information.

- Write down questions to ask. Preparing a list of questions will help you make the most of your time during your visit.

For seizures, some basic questions to ask your health care professional include:

- What do you think caused my seizure?

- Do I need to have any tests done?

- What treatment approach do you recommend?

- What are the alternatives to the primary approach that you're suggesting?

- How likely is it that I might have another seizure?

- How can I make sure that I don't hurt myself if I have another seizure?

- I have these other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there any restrictions that I need to follow?

- Should I see a specialist? What will that cost, and will my insurance cover it?

- Is there a generic alternative to the medicine you're prescribing?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take home with me? What websites do you recommend?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared, don't hesitate to ask any other questions you may have during your appointment and anytime that you don't understand something.

What to expect from your doctor

A health care professional is likely to ask you a number of questions:

- Can you describe your seizure episode?

- Where were you and what happened right before it started?

- Was anyone there to witness what happened?

- What do you remember feeling just before the seizure? What about right after the seizure?

- What symptoms did you experience?

- How long did the seizure last?

- Have you ever had a seizure or other neurological issue in the past?

- Do you have any family members who have been diagnosed with a seizures or epilepsy?

- Have you recently traveled outside the country?

Sept. 02, 2023