Feb. 05, 2021

As obesity has grown to affect 40% of the U.S. population and 60% of patients seeking kidney transplant, body mass index (BMI) — a traditional transplant criterion — has become a barrier. A large proportion of potential kidney transplant recipients currently have BMIs above 40.

While many transplant centers use a BMI cutoff of 35, Mayo Clinic's kidney transplant BMI cutoff is 40. However, Mayo staff encourages bariatric surgery for patients with morbid obesity to improve general health and potential post-transplant outcomes, even if they meet pre-specified BMI goals.

Two physicians at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, Aleksandra Kukla, M.D., a nephrologist, and Tayyab (Ty) S. Diwan, M.D., an abdominal transplant surgeon, have paved the way to transplant for patients with higher BMIs, using bariatric surgery to increase access. Outcomes are strong thus far for patients who have undergone this surgery prior to renal transplant, and mortality has not increased in patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy in the pretransplant setting.

Drs. Diwan and Kukla and colleagues in the Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition's advanced weight management program developed a streamlined program for patients with obesity and renal failure. The program is staffed by a bariatric and transplant surgeon, a nephrologist, an endocrinologist, dietitians, psychologists, and transplant and bariatric nurses. The team strives to identify patients with high BMI early, offering consult on risk and treatment. This alignment of bariatric and transplant disciplines is uncommon among medical centers, says Dr. Kukla.

She explains that Mayo is uniquely suited not only to address renal failure and kidney transplant but also to provide holistic care. Strong transplant, bariatric and endocrine services are opportune for treating bariatric issues in potential kidney transplant recipients. The collaboration among these groups means that in two to three days, patients can complete all examinations and testing rather than making countless visits.

Why obesity has been an issue with kidney transplant

Patients with high BMIs are not typically transplanted in the U.S. because they are part of a high-risk population that experiences increased complications perioperatively.

Comorbidities present in patients with obesity include diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, sleep apnea, increased cancer risk and infection rates, and frailty because obesity limits activity. Dr. Diwan explains that to many physicians, at issue is transplanting organs into unhealthy environments.

Obesity and diabetes also elevate cardiac event risk. Most patients with high BMI have increased visceral fat, predisposing to metabolic derangements that elevate cardiac risk. Patients seen for potential kidney transplant are already at the highest cardiovascular risk, says Dr. Kukla, noting that she sees even young patients who have had cardiac bypass. In addition, cardiac disease is a leading cause of death for patients while on dialysis and also post-transplantation.

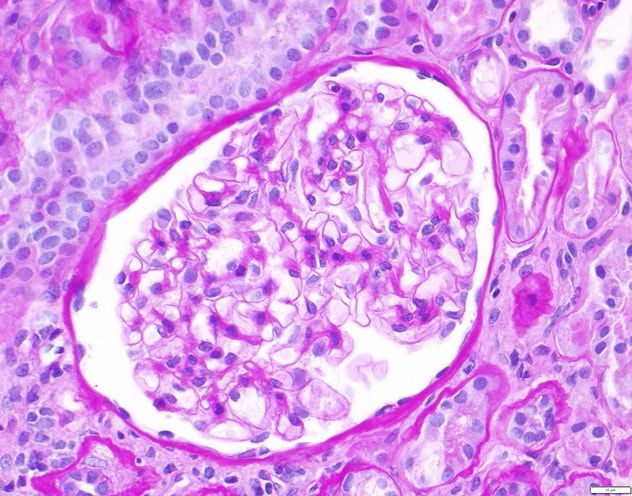

Normal glomerulus at time of transplant

Normal glomerulus at time of transplant

This picture (periodic acid-Schiff stain) shows normal glomerulus at the time of the transplant.

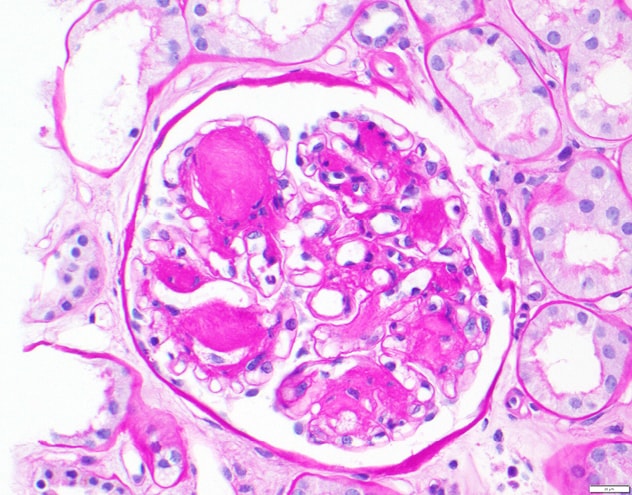

Nodular glomerulosclerosis (diabetic) five years posttransplant

Nodular glomerulosclerosis (diabetic) five years posttransplant

This picture (periodic acid-Schiff stain) represents what may happen to the kidney in a patient who is obese, and has diabetes, five years posttransplant. After five years, about 50% of patients with diabetes and obesity developed recurrent diabetic kidney disease in the renal allograft. Once this change develops, kidney survival is decreased and patients are at high risk of death.

Moreover, both obesity and diabetes affect kidney allograft outcomes. Patients developing renal failure due to diabetes, especially those with high BMI, are at risk of diabetic kidney disease recurrence in the allograft. In a study published in the November 2020 issue of Clinical Transplantation, Mayo Clinic researchers demonstrated a high incidence of moderate to severe mesangial expansion, a histologic hallmark of diabetic kidney disease, at five years post-transplant, which was associated with worse patient and kidney allograft survival.

Weight loss in the dialysis setting can be difficult due to associated fatigue, creating a negative cycle of minimal activity leading to more weight gain.

A nontraditional, inclusive approach

Undaunted by BMI restrictions, Drs. Diwan and Kukla feel passionately that the medical profession needs to help patients with obesity who need kidney transplant, prompting questions of how physicians can best care for them.

"In a perfect world, there should be no BMI cutoff," says Dr. Diwan. "If someone's BMI is 60, bring them over."

The traditional approach doesn't include helping patients with factors that make them transplant ineligible. Physicians typically instruct patients with obesity and diabetes to lose weight and return when this is accomplished.

Usually, patients unable to lose sufficient weight for transplant eligibility continue dialysis and die from their disease. According to the United States Renal Data System 2018 Annual Data Report, for patients starting dialysis in 2011, adjusted five-year survival from day 1 was 52% for those on peritoneal dialysis and 42% for those on hemodialysis. Dr. Kukla indicates that patients with diabetes would fare even worse. Most patients with diabetes aren't even able to make it to dialysis due to high cardiovascular mortality.

"Patients do better with transplant even without losing weight," says Dr. Diwan. "But there's a difference between better and ideal."

Dr. Kukla agrees that if a patient is healthy enough, transplant is always the best option. Bariatric surgery intervenes for patients with obesity, decreasing weight and comorbidities so they become transplant eligible.

In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2007, investigators compared standard weight loss via diet and exercise alone with bariatric surgery for patients with obesity. They found bariatric surgery to be most effective, improving health status and increasing life years.

Renal transplantation plus weight loss from bariatric surgery greatly improves patients' quality of life, says Dr. Diwan, as new mobility expands their range of experiences.

Timing of bariatric surgery and transplant, referrals

Drs. Diwan and Kukla advocate bariatric surgery first, then kidney transplant for patients with obesity. "Though you can perform bariatric surgery after transplantation or simultaneous to kidney transplant, often patients get declined because their BMIs are above 40 and they never get in the door," says Dr. Diwan. "So our thought is to do this on the front end."

Bariatric surgery addresses the common comorbidities previously mentioned, curing sleep apnea, treating type II diabetes and other chronic conditions and thereby decreasing transplant risk and promoting better kidney function post-surgery. If bariatric surgery allows a transplanted kidney to last an additional five years, it also impacts re-transplant need.

From a nephrologist's viewpoint, earlier intervention for patients with obesity in the pre-dialysis setting is better, explains Dr. Kukla. Bariatric surgery facilitates kidney stabilization; some patients may not need kidney transplant for years — perhaps ever. She says many patients with diabetes have heart attacks and die far before they ever receive a transplant; thus, she encourages prompt referral.

Dr. Diwan agrees that referring patients with obesity early in the kidney disease course can present opportunities to address weight loss and help patients become transplant eligible. "We really want to be able to take care of everybody who needs a kidney transplant," says Dr. Diwan.

For more information

Kukla A, at al. Mesangial expansion at 5 years predicts death and death-censored graft loss after renal transplantation. Clinical Transplantation. In press.

The United States Renal Data System Annual Data Report 2018.

Sjöström L, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007; 357:741.