Overview

Epilepsy surgery is a procedure to reduce seizures and improve the quality of life of people who have epilepsy.

Epilepsy surgery is most effective when seizures always occur in a single area in the brain. It's not the first line of treatment. But surgery is considered when at least two antiseizure medicines haven't been successful at managing seizures.

People with epilepsy might need several tests before surgery to find out whether epilepsy surgery is an option and what type of surgery to do.

Products & Services

Why it's done

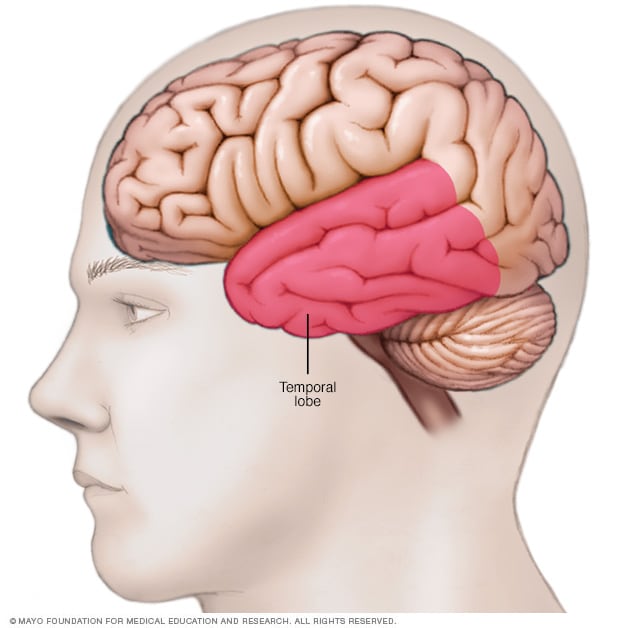

Location of temporal lobe

Location of temporal lobe

The temporal lobe is located along each side of the brain.

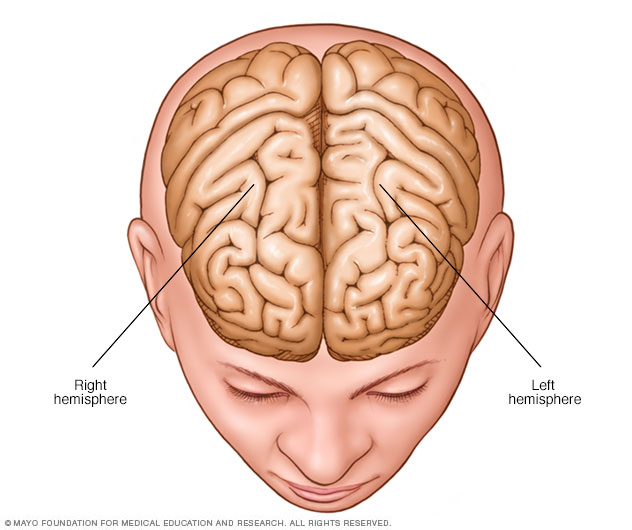

Brain hemispheres

Brain hemispheres

The brain is divided into two halves, called hemispheres.

Epilepsy surgery may be an option when medicines aren't able to manage seizures. This condition is known as medically refractory epilepsy. It also is called drug-resistant epilepsy. The goal of epilepsy surgery is to stop seizures or limit how bad they are.

After surgery, people generally need to remain on antiseizure medicines for at least two years. Over time, they may be able to lower the dose of their medicines or stop them completely.

Managing seizures is important because of the complications and health risks that can result if epilepsy isn't properly treated. Complications can include:

- Physical injuries during a seizure.

- Drowning, if the seizure occurs during a bath or swimming.

- Depression and anxiety.

- Developmental delays in children.

- Worsening memory or other thinking skills.

- Sudden death, a rare complication of epilepsy.

Types of epilepsy surgery

Epileptic seizures result from irregular activity of certain brain cells called neurons. The type of surgery to treat epileptic seizures depends on which area of the brain the seizures begin and the age of the person having the surgery. Types of surgery might include:

- Resective surgery. This surgery is the most common epilepsy surgery. With this surgery, the surgeon cuts out brain tissues in the area of the brain where seizures occur. The area may be the site of a tumor or brain injury. Resective surgery most often occurs on one of the temporal lobes. This area controls visual memory, language comprehension and emotions.

- Laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT). This procedure is less invasive than resective surgery. LITT uses a laser to pinpoint and destroy a small portion of brain tissue. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) helps guide the surgeon's laser.

- Deep brain stimulation. This procedure involves implanting electrodes deep inside the brain. A pacemakerlike device also is placed under the skin in the chest. A wire connects this device to the electrodes in the brain. The electrodes send electrical impulses to disrupt seizure-causing activity. Like LITT, this procedure is guided by MRI.

- Corpus callosotomy. This surgery completely or partially removes part of the brain that connects nerves on the right and left sides of the brain. This area is called the corpus callosum. This procedure is performed most often on children who experience irregular brain activity that spreads from one side of the brain to the other.

- Hemispherectomy. This procedure removes one side of the brain, called a hemisphere, which is part of the folded gray matter of the brain. The gray matter area is called the cerebral cortex. This surgery is usually performed only in children who have seizures that start in different areas within one brain hemisphere. These types of seizures usually result from a condition that is present at birth or in early infancy.

- Functional hemispherectomy. This procedure is mostly performed on children to remove the connecting nerves without removing actual pieces of the brain.

Risks

The risks of epilepsy surgery may vary because different areas of the brain control different functions. The risks depend on the area of the brain and the type of surgery. Your surgical team explains the specific risks of your procedure and the strategies the team uses to reduce the risk of complications. Risks may include:

- Trouble with memory and language, which can affect your ability to communicate with and understand others.

- Visual changes where the fields of vision of your eyes overlap.

- Depression or other mood changes that can affect relationships or social well-being.

- Headache.

- Stroke.

How you prepare

To prepare for epilepsy surgery, you work with a healthcare team at a specialized epilepsy center. The healthcare team does several tests to:

- Learn if you are a candidate for surgery.

- Find the area of the brain that needs treatment.

- Understand in detail how that area of the brain functions.

Some of these tests are performed as outpatient procedures. Others require a hospital stay.

Evaluations to find the source of seizure activity

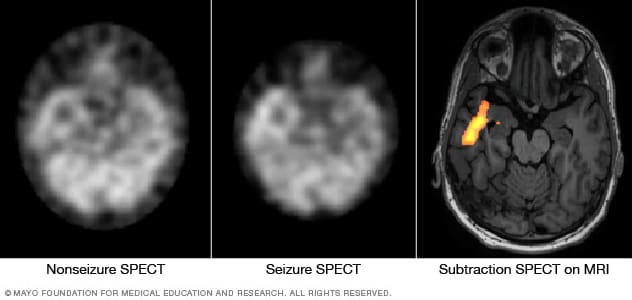

Pinpointing seizure location

Pinpointing seizure location

These SPECT images show the blood flow in the brain of a person when there's no seizure activity (left) and during a seizure (middle). The subtraction SPECT coregistered to MRI (right) helps pinpoint the area of seizure activity by overlapping the SPECT results with brain MRI results.

These procedures are standard tests to identify the source of irregular brain activity.

- Baseline electroencephalogram EEG. In this test, electrodes are placed on the scalp to measure electrical activity produced by the brain when you're not experiencing a seizure. A baseline EEG can suggest which general areas of the brain may be affected by seizures.

- Video EEG. A continuous EEG with video monitoring records the seizures as they occur. Because your antiseizure medicines have to be reduced or stopped for a short time so that seizures will occur, you need to be admitted to the hospital for this test. Evaluating the changes in your EEG along with your body's movements during a seizure helps to pinpoint the area of your brain where your seizures start.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This type of imaging test uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create detailed images that help healthcare professionals identify damaged cells or tumors that can cause seizures.

Your surgical team also may order other tests to find the source of seizures and understand the type of irregular brain activity that is causing them. These tests may include:

- Invasive EEG monitoring. If an EEG test does not show where seizures begin, monitoring may be done with surgically placed electrodes. The surgeon places either grids or strips of electrodes on the surface of the brain or places electrodes deeper inside the brain. EEG monitoring is done while you're unconscious.

- Video EEG with invasive electrodes. Surgically placed electrodes also may be needed for a video EEG procedure. After the surgery, the video and EEG data are captured during a hospital stay while you're awake but not taking antiseizure medicines.

- Positron emission tomography (PET). This specialized imaging device measures brain function when you're seizure-free. The images alone or combined with MRI data can help identify the source of your seizures.

- Single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT). This procedure measures blood flow in the brain during a seizure. Typically, blood flow is higher in the part of the brain where seizures occur. You are admitted to the hospital to have this test.

Evaluations to understand brain function

Depending on the surgical site, your healthcare team may recommend tests to determine the precise areas of the brain that control language, sensory functions, motor skills or other critical functions. This information helps your surgeon protect these functions as well as possible when removing or changing an area of your brain.

The tests may include:

- Functional MRI. This test identifies regions of brain activity when you're doing a particular task, such as listening or reading. This helps the surgeon know the exact areas in your brain that control specific functions.

- Wada test. With this test, an injected medicine puts one side of your brain to sleep for a short time. This happens with one side of your brain at a time. You then take a test that checks your language and memory abilities. This test can help show which side of your brain controls your language usage. While functional MRI mostly has replaced this test, the Wada test may be used if imaging isn't an option.

- Brain mapping. Small electrodes are surgically placed on the surface of the brain. When you're alert after the surgery, you perform tasks that are matched with measurements of your brain's electrical activity.

- Magnetoencephalography (MEG). This test analyzes the magnetic fields produced by the electrical currents in the brain. MEG is used with data from other sources to find seizure sites.

Neuropsychological tests

These types of tests also are recommended to measure verbal and nonverbal learning skills and memory function. These tests may help your healthcare team to better understand the area of the brain affected by seizures. The tests also provide a baseline for measuring brain function after surgery.

What you can expect

Before the procedure

To avoid infection, your hair is clipped short or shaved over the section of your skull that is removed during the procedure. A small, flexible tube is placed within a vein to deliver IV fluids, anesthetics or other medicines during the surgery.

During the procedure

Your heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen levels are monitored throughout the surgery. An EEG monitor also may record your brain waves to better locate the part of your brain where your seizures start.

Epilepsy surgery is usually performed during general anesthesia, and you'll be in a sleeplike state during the procedure. Rarely, your surgeon may awaken you during part of the procedure to help determine which parts of your brain control language and movement. If this happens, medicine is used to control pain.

The surgeon may create a small window in the skull, depending on the type of surgery. After surgery, the window of bone is replaced and fastened to the remaining skull for healing.

After the procedure

After the procedure, you are in a recovery area and monitored carefully as you awaken from anesthesia. You may need to spend the first night after surgery in an intensive care unit. The total hospital stay for most epilepsy surgeries is usually about three or four days.

When you awaken, your head may be swollen and painful. Most people need to take pain medicine for at least the first few days. An ice pack on your head also may help. Most postoperative swelling and pain resolve within several weeks.

Most people are not able to return to work or school for about 1 to 3 months. Rest and relaxation are needed for the first few weeks after epilepsy surgery and then physical activity can be increased.

Rehabilitation may help people who are at risk of having trouble with brain function after surgery.

Results

The outcomes of epilepsy surgery vary depending on the type of surgery. The expected outcome is seizure management with medicine.

The most common procedure — resection of tissue in the temporal lobe — results in seizure-free outcomes for about two-thirds of people. Studies suggest that if a person takes antiseizure medicine and does not have a seizure in the first year after temporal lobe surgery, the likelihood of being seizure-free at two years is 87% to 90%. If there are no seizures in two years, the likelihood of being seizure-free is 95% at five years and 82% at 10 years.

If you remain seizure-free for at least one year, your healthcare professional may consider reducing your antiseizure medicine over time. Eventually you may stop taking the medicine. Most people who have a seizure after going off their antiseizure medicine are able to manage their seizures again by restarting the medicine.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Nov. 14, 2024