Overview

Measles is a childhood infection caused by a virus. Once quite common, measles can now almost always be prevented with a vaccine.

Also called rubeola, measles spreads easily and can be serious and even fatal for small children. While death rates have been falling worldwide as more children receive the measles vaccine, the disease still kills more than 200,000 people a year, mostly children.

As a result of high vaccination rates in general, measles hasn't been widespread in the United States in about two decades. Most recent measles cases in the U.S. originated outside the country and occurred in people who were unvaccinated or who didn't know whether or not they had been vaccinated.

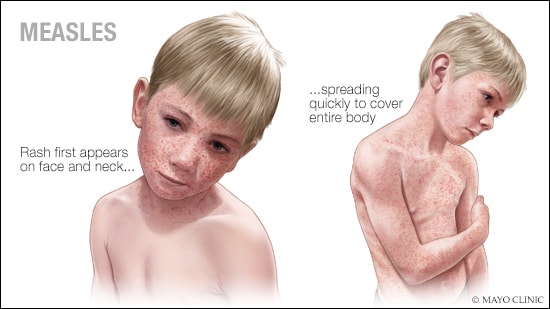

Measles

Measles causes a red, blotchy rash that usually appears first on the face and behind the ears, then spreads downward to the chest and back and finally to the feet.

Symptoms

Measles signs and symptoms appear around 10 to 14 days after exposure to the virus. Signs and symptoms of measles typically include:

- Fever

- Dry cough

- Runny nose

- Sore throat

- Inflamed eyes (conjunctivitis)

- Tiny white spots with bluish-white centers on a red background found inside the mouth on the inner lining of the cheek — also called Koplik's spots

- A skin rash made up of large, flat blotches that often flow into one another

The infection occurs in stages over 2 to 3 weeks.

- Infection and incubation. For the first 10 to 14 days after infection, the measles virus spreads in the body. There are no signs or symptoms of measles during this time.

- Nonspecific signs and symptoms. Measles typically begins with a mild to moderate fever, often with a persistent cough, a runny nose, inflamed eyes (conjunctivitis) and a sore throat. This relatively mild illness may last 2 to 3 days.

Acute illness and rash. The rash is made up of small red spots, some of which are slightly raised. Spots and bumps in tight clusters give the skin a splotchy red appearance. The face breaks out first.

Over the next few days, the rash spreads down the arms, chest and back, then over the thighs, lower legs and feet. At the same time, the fever rises sharply, often as high as 104 to 105.8 F (40 to 41 C).

- Recovery. The measles rash may last about seven days. The rash gradually fades first from the face and last from the thighs and feet. As other symptoms of the illness go away, the cough and darkening or peeling of the skin where the rash was may stay for about 10 days.

When can a person spread the measles virus?

A person with measles can spread the virus to others for about eight days, starting four days before the rash appears and ending when the rash has been present for four days.

When to see a doctor

Call your health care provider if you think you or your child may have been exposed to measles or if you or your child has a rash that looks like measles.

Review your family's vaccination records with your provider, especially before your children start day care, school or college and before international travel outside of the U.S.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Causes

Measles is a highly contagious illness. This means it's very easily spread to others. Measles is caused by a virus found in the nose and throat of an infected child or adult. When someone with measles coughs, sneezes or talks, infectious droplets spray into the air, where other people can breathe them in. The infectious droplets can hang in the air for about an hour.

The infectious droplets may also land on a surface, where they can live and spread for several hours. You can get the measles virus by putting your fingers in your mouth or nose or rubbing your eyes after touching the infected surface.

Measles is highly contagious from about four days before to four days after the rash appears. About 90% of people who haven't had measles or been vaccinated against measles will become infected when exposed to someone with the measles virus.

Risk factors

Risk factors for measles include:

- Being unvaccinated. If you haven't had the measles vaccine, you're much more likely to get measles.

- Traveling internationally. If you travel to countries where measles is more common, you're at higher risk of catching measles.

- Having a vitamin A deficiency. If you don't have enough vitamin A in your diet, you're more likely to have more-severe symptoms and complications of measles.

Complications

Complications of measles may include:

- Diarrhea and vomiting. Diarrhea and vomiting can result in losing too much water from the body (dehydration).

- Ear infection. One of the most common complications of measles is a bacterial ear infection.

- Bronchitis, laryngitis or croup. Measles may lead to irritation and swelling (inflammation) of the airways (croup). It can also lead to inflammation of the inner walls that line the main air passageways of the lungs (bronchitis). Measles can also cause inflammation of the voice box (laryngitis).

- Pneumonia. Measles can commonly cause an infection in the lungs (pneumonia). People with weakened immune systems can develop an especially dangerous type of pneumonia that sometimes can lead to death.

- Encephalitis. About 1 in 1,000 people with measles can develop a complication called encephalitis. Encephalitis is irritation and swelling (inflammation) of the brain. The condition can be especially dangerous for people with weakened immune systems. Encephalitis may occur right after measles, or it might not occur until months later. Encephalitis can cause permanent brain damage.

- Pregnancy problems. If you're pregnant, you need to take special care to avoid measles because the disease can cause premature birth, low birth weight and fetal death.

Prevention

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that children and adults receive the measles vaccine to prevent measles.

Measles vaccine in children

The measles vaccine is usually given as a combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. This vaccine may also include the chickenpox (varicella) vaccine — measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine. Health care providers recommend that children receive the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine between 12 and 15 months of age, and again between 4 and 6 years of age — before entering school.

The MMR vaccine's two doses are 97% effective in preventing measles and protecting against it for life. In the small number of people who get measles after being vaccinated, the symptoms are generally mild.

Keep in mind:

- If you'll be traveling internationally outside the U.S. when your child is 6 to 11 months old, talk with your child's health care provider about getting the measles vaccine earlier.

- If your child or teenager didn't get the two doses of the vaccine at the recommended times, your child may need two doses of the vaccine four weeks apart.

Babies born to women who have received the vaccine or who are already immune because they had measles are usually protected from measles for about 6 months after birth. If a child requires protection from measles before 12 months of age — for example, for foreign travel — the vaccine can be given as early as 6 months of age. But children who are vaccinated early still need to be vaccinated at the recommended ages later.

Providing a child with the MMR vaccine as a combination of recommended vaccines can prevent a child's delay in protection against infection from measles, mumps and rubella — and with fewer shots. The combination vaccine is as safe and effective as the vaccines given separately. Side effects are generally mild and may include a sore arm where the shot was given and fever.

Measles vaccine in adults

You may need the measles vaccine if you're an adult who does not have proof of immunity and:

- Has an increased risk of measles, such as attending college, traveling internationally outside the U.S. or working in a hospital environment.

- Was born in 1957 or later. If you've already had measles, your body has built up its immune system to fight the infection, and you can't get measles again. Most people born or living in the U.S. before 1957 are immune to measles, simply because they've already had it.

Proof of immunity — protection from getting measles infection — includes:

- Written documentation of appropriate measles vaccinations

- Lab tests that show evidence of immunity

- Lab tests that show you've had measles in the past

If you're not sure if you need the measles vaccine, talk to your health care provider.

Preventing measles during an outbreak or known infection

If someone in your household has measles, take these precautions to protect family and friends without immunity:

Isolate. Because measles is highly contagious from about four days before to four days after the rash appears, people with measles should stay home and not return to activities where they interact with other people during this period.

People who aren't vaccinated — siblings, for example — should also stay away from the infected person.

- Vaccinate. Be sure that anyone who's at risk of getting measles who hasn't been fully vaccinated receives the measles vaccine as soon as possible. This includes infants older than 6 months and anyone born in 1957 or later who doesn't have proof of immunity.

Preventing new infections

Getting vaccinated with the measles vaccine is important for:

Promoting and preserving widespread immunity. Since the introduction of the measles vaccine, measles has virtually been eliminated in the U.S., even though not everyone has been vaccinated. This effect is called herd immunity.

But herd immunity may now be weakening a bit, likely due to a drop in vaccination rates. The incidence of measles in the U.S. recently increased significantly.

Preventing a resurgence of measles. Steady vaccination rates are important because soon after vaccination rates decline, measles begins to come back.

Here's one example. In 1998, a now-discredited study was published incorrectly linking autism to the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. In the United Kingdom, where the study originated, the rate of vaccination dropped to an all-time low of about 80% of all children in 2003 to 2004. In 2008, there were nearly 1,400 lab-confirmed cases of measles in England and Wales.

No proven link between the MMR vaccine and autism

After the MMR study in 1998, some drops in vaccine numbers were found in the UK and elsewhere, and some people believed there was a possible link. Since then, widespread concerns have been raised about a possible link between the MMR vaccine and autism. However, extensive reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics, the National Academy of Medicine, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conclude that there is no scientifically proven link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

These organizations note that autism is often identified in toddlers between the ages of 18 and 30 months, which is about the time children are given their first MMR vaccine. But this coincidence in timing shouldn't be mistaken for a cause-and-effect relationship.