Overview

Mitral valve regurgitation is the most common type of heart valve disease. In this condition, the valve between the left heart chambers doesn't close fully. Blood leaks backward across the valve. If the leakage is severe, not enough blood moves through the heart or to the rest of the body. Mitral valve regurgitation can make you feel very tired or short of breath.

Other names for mitral valve regurgitation are:

- Mitral regurgitation (MR).

- Mitral insufficiency.

- Mitral incompetence.

Treatment of mitral valve regurgitation may include regular health checkups, medicines or surgery. You may not need treatment if the condition is mild.

Severe mitral valve regurgitation often requires a catheter procedure or heart surgery to repair or replace the mitral valve. Without proper treatment, severe mitral valve regurgitation can cause heart rhythm problems or heart failure.

Video: Mitral valve regurgitation

The mitral valve is located between the upper left heart chamber (left atrium) and the lower left heart chamber (left ventricle). A healthy mitral valve keeps your blood moving in the right direction. A leaky valve doesn't close the way it should, allowing some blood to flow backward into the left atrium. If left untreated, a leaky valve could lead to heart failure.

Symptoms

Mitral valve regurgitation is often mild and develops slowly. Some people do not have symptoms for many years.

But sometimes, mitral valve regurgitation develops quickly. When this happens, it's called acute mitral valve regurgitation.

Fatigue is a common but nonspecific symptom of mitral valve regurgitation. Other symptoms of mitral valve regurgitation include:

- Irregular heartbeat, called an arrhythmia.

- Shortness of breath, especially when lying down.

- Feelings of a rapid, pounding or fluttering heartbeat, called palpitations.

- Swollen feet or ankles.

When to see a doctor

If you have symptoms of mitral valve regurgitation, make an appointment for a health checkup.

You may be referred to a doctor trained in heart diseases, called a cardiologist.

Causes

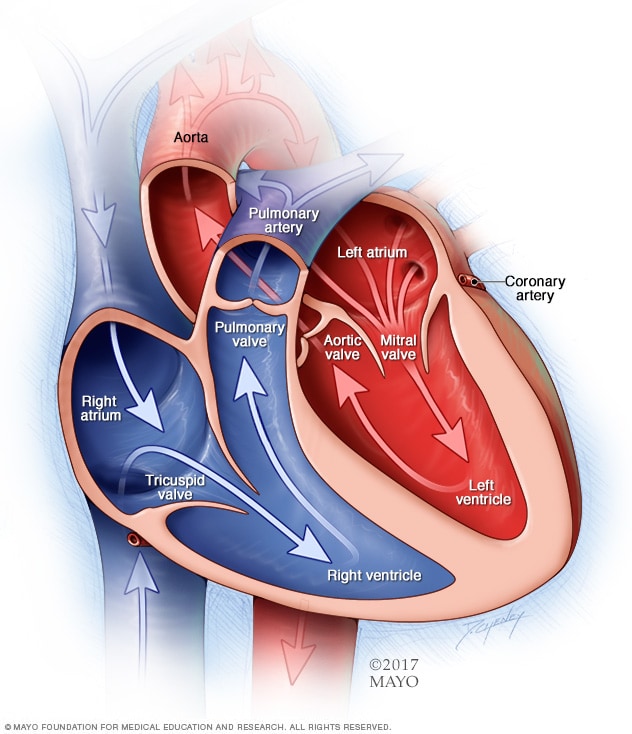

Chambers and valves of the heart

Chambers and valves of the heart

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of the heart. The heart valves help keep blood flowing in the right direction.

To understand the causes of mitral valve disease, it may be helpful to know how the heart works.

The mitral valve is one of four valves in the heart that keep blood flowing in the right direction. Each valve has flaps, also called leaflets, that open and close once during each heartbeat.

In mitral valve regurgitation, the valve flaps don't close tightly. Blood moves backward when the valve is closed. This makes it harder for the heart to work properly.

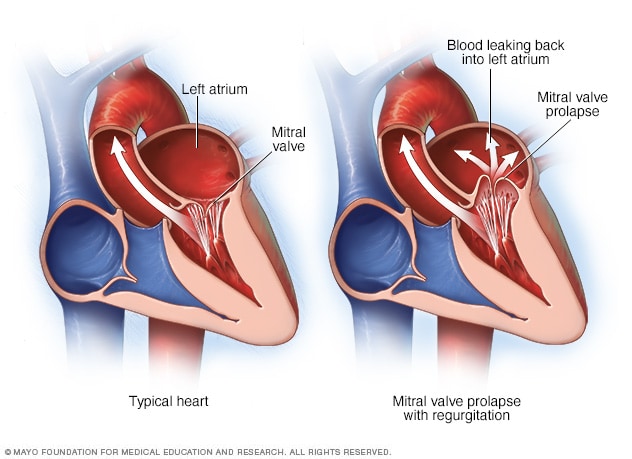

Mitral valve prolapse and regurgitation

Mitral valve prolapse and regurgitation

The mitral valve separates the two chambers of the left side of the heart. In mitral valve prolapse, the valve flaps bulge into the upper left chamber during each heartbeat. Mitral valve prolapse can cause blood to leak backward, a condition called mitral valve regurgitation.

If mitral valve regurgitation is due to problems with the mitral valve, the condition is called primary mitral valve regurgitation.

If a problem or disease affecting other areas of the heart cause a leaky mitral valve, the condition is called functional or secondary mitral regurgitation.

Possible causes of mitral valve regurgitation include:

- Mitral valve prolapse. In this condition, the mitral valve's flaps bulge back into the left upper heart chamber when the heart squeezes. This common heart problem can prevent the mitral valve from closing tightly and cause blood to flow backward.

- Rheumatic fever. Rheumatic fever is a complication of untreated strep throat. Rheumatic fever can damage the mitral valve, leading to mitral valve regurgitation early or later in life. If rheumatic fever causes mitral valve disease, the condition is called rheumatic mitral valve disease. Rheumatic fever is rare in the United States.

- Heart attack. A heart attack can damage the area of the heart muscle that supports the mitral valve. If there is a lot of heart attack damage, sudden and severe mitral valve regurgitation can occur. A leaky mitral valve caused by a heart attack is called ischemic mitral regurgitation.

- Heart problem present at birth, also called a congenital heart defect. Some people are born with heart structure problems, including damaged heart valves.

- Thickening of the heart muscle, called cardiomyopathy. Cardiomyopathy makes it harder for the heart to pump blood to the rest of the body. The condition can affect how the mitral valve works, causing regurgitation. Types of cardiomyopathy linked to mitral valve regurgitation include dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

- Damaged tissue cords. Over time, the pieces of tissue that hold the flaps of the mitral valve to the heart wall may stretch or tear. This is especially likely in people with mitral valve prolapse. A tear can cause blood to suddenly leak through the mitral valve. It may require mitral valve repair surgery. A chest injury also can cause rupture of the cords.

- Inflammation of the inner lining of the heart's chambers and valves, called endocarditis. This condition is usually caused by an infection. Germs get into the bloodstream and attach to damaged areas in the heart.

- Radiation therapy. Rarely, radiation therapy for cancer that is focused on the chest area can lead to mitral valve regurgitation.

Risk factors

Several things can increase the risk of mitral valve regurgitation, including:

- Certain infections that affect the heart.

- Heart attack.

- Heart problems present at birth, called congenital heart defects.

- History of other heart valve diseases, including mitral valve prolapse and mitral valve stenosis.

- Older age.

- Radiation to the chest.

Complications

Mitral valve regurgitation complications often depend on the severity of disease. Mild mitral valve regurgitation usually does not cause any problems.

As mitral valve regurgitation gets worse, the heart must work harder to pump blood to the body. The strain on the heart can cause the left lower chamber to widen. The heart muscle may become weak.

Potential complications of severe mitral valve regurgitation include:

- An irregular and often rapid heartbeat, called atrial fibrillation. Mitral valve regurgitation may trigger this common heart rhythm disorder. Atrial fibrillation has been linked to an increased risk of blood clots and stroke.

- High blood pressure in the lungs, called pulmonary hypertension. Long-term untreated or improperly treated mitral regurgitation can increase pressure in the blood vessels in the lungs. As pressure rises, fluid builds up in the lungs.

- Congestive heart failure. In severe mitral valve regurgitation, the heart has to work harder to pump enough blood to the body. The extra effort causes the left lower heart chamber to get bigger. Untreated, the heart muscle becomes weak. This can cause heart failure.

Sept. 19, 2023