Overview

Myomectomy (my-o-MEK-tuh-me) is a surgical procedure to remove uterine fibroids — also called leiomyomas (lie-o-my-O-muhs). These common noncancerous growths appear in the uterus. Uterine fibroids usually develop during childbearing years, but they can occur at any age.

The surgeon's goal during myomectomy is to take out symptom-causing fibroids and reconstruct the uterus. Unlike a hysterectomy, which removes your entire uterus, a myomectomy removes only the fibroids and leaves your uterus.

Women who undergo myomectomy report improvement in fibroid symptoms, including decreased heavy menstrual bleeding and pelvic pressure.

Why it's done

Your doctor might recommend myomectomy for fibroids causing symptoms that are troublesome or interfere with your normal activities. If you need surgery, reasons to choose a myomectomy instead of a hysterectomy for uterine fibroids include:

- You plan to bear children

- Your doctor suspects uterine fibroids might be interfering with your fertility

- You want to keep your uterus

Risks

Myomectomy has a low complication rate. Still, the procedure poses a unique set of challenges. Risks of myomectomy include:

Excessive blood loss. Many women with uterine leiomyomas already have low blood counts (anemia) due to heavy menstrual bleeding, so they're at a higher risk of problems due to blood loss. Your doctor may suggest ways to build up your blood count before surgery.

During myomectomy, surgeons take extra steps to avoid excessive bleeding. These may include blocking flow from the uterine arteries by using tourniquets and clamps and injecting medications around fibroids to cause blood vessels to clamp down. However, most steps don't reduce the risk of needing a transfusion.

In general, studies suggest that there is less blood loss with hysterectomy than myomectomy for similarly sized uteruses.

- Scar tissue. Incisions into the uterus to remove fibroids can lead to adhesions — bands of scar tissue that may develop after surgery. Laparoscopic myomectomy may result in fewer adhesions than abdominal myomectomy (laparotomy).

- Pregnancy or childbirth complications. A myomectomy can increase certain risks during delivery if you become pregnant. If your surgeon had to make a deep incision in your uterine wall, the doctor who manages your subsequent pregnancy may recommend cesarean delivery (C-section) to avoid rupture of the uterus during labor, a very rare complication of pregnancy. Fibroids themselves are also associated with pregnancy complications.

- Rare chance of hysterectomy. Rarely, the surgeon must remove the uterus if bleeding is uncontrollable or other abnormalities are found in addition to fibroids.

Rare chance of spreading a cancerous tumor. Rarely, a cancerous tumor can be mistaken for a fibroid. Taking out the tumor, especially if it's broken into little pieces (morcellation) to remove through a small incision, can lead to spread of the cancer. The risk of this happening increases after menopause and as women age.

In 2014, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cautioned against using a laparoscopic power morcellator for most women undergoing myomectomy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends you talk to your surgeon about the risks and benefits of morcellation.

Strategies to prevent possible surgical complications

To minimize risks of myomectomy surgery, your doctor may recommend:

- Iron supplements and vitamins. If you have iron deficiency anemia from heavy menstrual periods, your doctor might recommend iron supplements and vitamins to allow you to build up your blood count before surgery.

- Hormonal treatment. Another strategy to correct anemia is hormonal treatment before surgery. Your doctor may prescribe a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist, birth control pills or other hormonal medication to stop or decrease your menstrual flow. When given as therapy, a GnRH agonist blocks the production of estrogen and progesterone, stopping menstruation and allowing you to rebuild hemoglobin and iron stores.

Therapy to shrink fibroids. Some hormonal therapies, such as GnRH agonist therapy, can also shrink your fibroids and uterus enough to allow your surgeon to use a minimally invasive surgical approach — such as a smaller, horizontal incision rather than a vertical incision, or a laparoscopic procedure instead of an open procedure.

Some research suggests that intermittent GnRH agonist therapy, over time, can shrink fibroids and decrease bleeding enough that surgery isn't needed.

In most women, GnRH agonist therapy causes symptoms of menopause, including hot flashes, night sweats and vaginal dryness. However, these discomforts end after you stop taking the medication. Treatment generally occurs over several months before surgery.

Evidence suggests that not all women should take GnRH agonist therapy before myomectomy. GnRH agonist therapy may soften and shrink fibroids so much that their detection becomes more difficult. The cost of the medication and the risk of side effects must be weighed against the benefits.

Another family of drugs called selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), such as ulipristal (ella), may also shrink fibroids and reduce bleeding. Outside the United States, ulipristal is approved for three months of therapy before a myomectomy.

How you prepare

Food and medications

You'll need to fast — stop eating or drinking anything — in the hours before your surgery. Follow your doctor's recommendation on the specific number of hours.

If you're on medications, ask your doctor if you should change your usual medication routine in the days before surgery. Tell your doctor about any over-the-counter medications, vitamins or other dietary supplements you're taking.

Depending on your procedure, you may receive one of the following types of anesthesia:

- General anesthesia. With general anesthesia, you will be fully asleep and a tube will be placed in your throat. General anesthesia is used for laparoscopic myomectomy and usually for abdominal myomectomy; it is sometimes also used for hysteroscopic myomectomy.

- Monitored anesthesia care (MAC). With this type of anesthesia, you typically don't remember anything and feel as if you're fully asleep. You don't have a tube placed in your throat. MAC is often used for hysteroscopic myomectomy, since it's a less invasive procedure and therefore requires less anesthesia.

Sometimes other types of anesthesia, such as a spinal or local, may be used. Ask your doctor about the type of anesthesia you may receive.

Finally, talk to your doctor about pain medication and how it will likely be given.

Other preparations

Whether you stay in the hospital for just part of the day or overnight depends on the type of procedure you have. Abdominal myomectomy (laparotomy) usually requires a hospital stay of one to two days. In most cases, laparoscopic or robotic myomectomy is done outpatient or with only one overnight stay. Hysteroscopic myomectomy is often done with no overnight hospital stay.

Your facility may require that you have someone accompany you on the day of surgery. Make sure you have someone lined up to help with transportation and to be supportive.

What you can expect

Fibroid locations

Fibroid locations

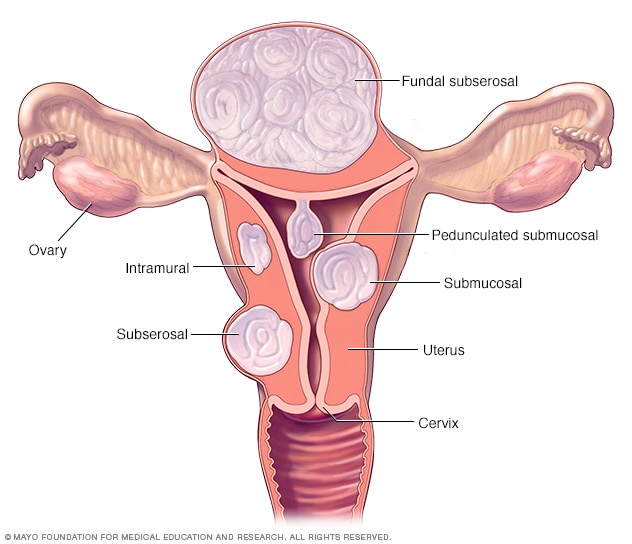

There are three major types of uterine fibroids. Intramural fibroids grow within the muscular uterine wall. Submucosal fibroids bulge into the uterine cavity. Subserosal fibroids project to the outside of the uterus. Some submucosal or subserosal fibroids may be pedunculated. This means they hang from a stalk inside or outside the uterus.

Depending on the size, number and location of your fibroids, your surgeon may choose one of three surgical approaches to myomectomy.

Abdominal myomectomy

In abdominal myomectomy (laparotomy), your surgeon makes an open abdominal incision to access your uterus and remove fibroids. Your surgeon will generally prefer to make a low, horizontal ("bikini line") incision, if possible. Vertical incisions are needed for larger uteruses.

Laparoscopic or robotic myomectomy

In laparoscopic or robotic myomectomy, both minimally invasive procedures, your surgeon accesses and removes fibroids through several small abdominal incisions.

Compared with women who have a laparotomy, women who undergo laparoscopy have less blood loss, shorter hospital stays and recovery, and lower rates of complications and adhesion formation after surgery. There are limited comparisons between laparoscopic and robotic myomectomy. Robotic surgery may take longer and be more costly, but otherwise few differences in outcomes are reported.

- Laparoscopic myomectomy. Your surgeon makes a small incision in or near your bellybutton. Then he or she inserts a laparoscope — a narrow tube fitted with a camera — into your abdomen. Your surgeon performs the surgery with instruments inserted through other small incisions in your abdominal wall.

- Robotic myomectomy. Your surgeon inserts instruments through small incisions similar to those in a laparoscopic myomectomy, and then controls movement of the instruments from a separate console. Some surgeons are now performing single-port (one incision) laparoscopic and robotic myomectomies.

Sometimes, the fibroid is cut into pieces (morcellation) and removed through a small incision in the abdominal wall. Other times the fibroid is removed through a bigger incision in your abdomen so that it can be removed without being cut into pieces. Rarely, the fibroid may be removed through an incision in your vagina (colpotomy).

Hysteroscopic myomectomy

To treat smaller fibroids that bulge significantly into your uterus (submucosal fibroids), your surgeon may suggest a hysteroscopic myomectomy. Your surgeon accesses and removes the fibroids using instruments inserted through your vagina and cervix into your uterus.

A hysteroscopic myomectomy generally follows this process:

- Your surgeon inserts a small, lighted instrument through your vagina and cervix and into your uterus. He or she will most commonly use either a wire loop resectoscope to cut (resect) tissue using electricity or a hysteroscopic morcellator to manually cut the fibroid with a blade.

- A clear liquid, usually a sterile salt solution, is inserted into your uterus to expand your uterine cavity and allow examination of the uterine walls.

- Your surgeon shaves pieces from the fibroid using the resectoscope or the hysteroscopic morcellator, taking out the pieces from the uterus until the fibroid is completely removed. Sometimes large fibroids can't be fully removed in one surgery, and a second surgery is needed.

After the procedure

At discharge from the hospital, your doctor prescribes oral pain medication, tells you how to care for yourself, and discusses restrictions on your diet and activities. You can expect some vaginal spotting or staining for a few days up to six weeks, depending on the type of procedure you've had.

Results

Outcomes from myomectomy may include:

- Symptom relief. After myomectomy surgery, most women experience relief of bothersome signs and symptoms, such as excessive menstrual bleeding and pelvic pain and pressure.

- Fertility improvement. Women who undergo laparoscopic myomectomy, with or without robotic assistance, have good pregnancy outcomes within about a year of surgery. After a myomectomy, suggested waiting time is three to six months before attempting conception to allow your uterus time to heal.

Fibroids that your doctor doesn't detect during surgery or fibroids that are not completely removed could eventually grow and cause symptoms. New fibroids, which may or may not require treatment, can also develop. Women who had only one fibroid have a lower risk of developing new fibroids — often termed the recurrence rate — than do women who had multiple fibroids. Women who become pregnant after surgery also have a lower risk of developing new fibroids than women who don't become pregnant.

Women who have new or recurring fibroids may have additional, nonsurgical treatments available to them in the future. These include:

- Uterine artery embolization (UAE). Microscopic particles are injected into one or both uterine arteries, limiting blood supply.

- Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RVTA). Radiofrequency energy is used to wear away (ablate) fibroids using friction or heat — for instance, guided by an ultrasound probe.

- MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS). A heat source is used ablate fibroids, guided by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Some women with new or recurring fibroids may choose a hysterectomy if they have completed childbearing.