Overview

Middle ear

Middle ear

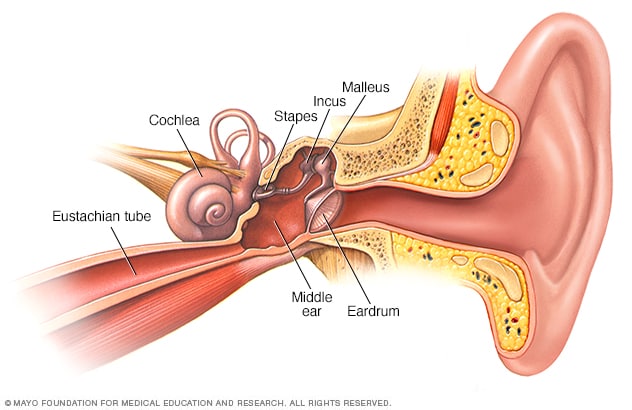

The middle ear includes three small bones. They are the hammer, called the malleus; the anvil, known as the incus; and the stirrup, known as the stapes. The eardrum lies between the middle ear and outer ear. The middle ear connects to the back of the nose and throat by a narrow area called the eustachian tube. The snail-shaped cochlea is part of the inner ear.

Tympanostomy tubes

Tympanostomy tubes

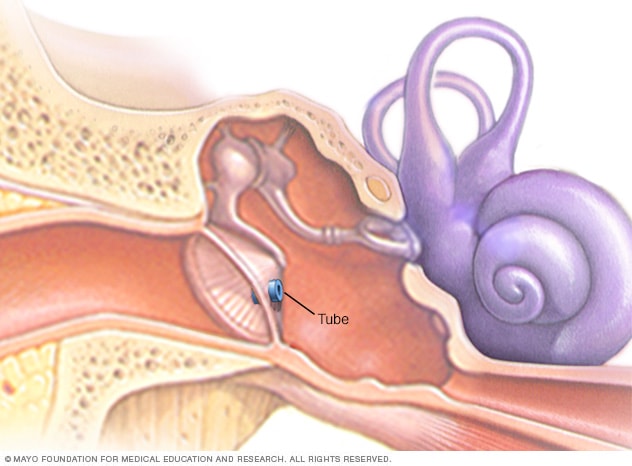

Ear tubes are tiny, hollow tubes usually made of plastic or metal. Surgeons place them into the eardrums during surgery. The tube makes an airway that keeps fluid from building up behind the eardrum. Ear tubes also are called tympanostomy tubes, ventilation tubes, myringotomy tubes or pressure equalization tubes.

Ear tubes are tiny, hollow tubes that surgeons place into the eardrums during surgery. An ear tube allows air into the middle ear. Ear tubes keep fluid from building up behind the eardrums. The tubes usually are made of plastic or metal.

Ear tubes also are called tympanostomy tubes, ventilation tubes, myringotomy tubes or pressure equalization tubes.

Ear tubes might help children who have repeated, long-lasting ear infections, also known as chronic otitis media. Ear tubes also might help children who still have fluid buildup in the ear after an infection clears up. This is called otitis media with effusion.

Most ear tubes are made to fall out in 4 to 18 months. The holes heal on their own. Some tubes are meant to stay in longer. Surgeons might need to remove them in a second surgery. The holes might need to be closed with surgery, as well.

Why it's done

An ear tube is used to treat and prevent the buildup of fluids in the middle ear.

The middle ear

The middle ear is the space behind the eardrum that has three tiny bones that vibrate. An opening in the middle ear leads to a tube that connects the middle ear to the back of the throat, also known as the eustachian tube. This tube has three jobs:

- Keep air pressure even in the middle ear.

- Bring fresh air to the ear.

- Drain fluids from the middle ear.

The eustachian tubes of young children are narrower and more level than adults' eustachian tubes are. So they're harder to drain and more likely to get clogged.

Problems with the middle ear

Conditions treated with ear tubes have:

- Swelling and irritation, also called inflammation.

- Buildup of fluids.

Ear tubes might treat the following conditions:

- Middle ear infection, known as acute otitis media. Bacteria or viruses cause this infection. It causes inflammation and fluids in the middle ear. Ear tubes might help prevent new infections. Children who have three or more infections in six months or four or more infections in a year might be helped from ear tubes.

-

Buildup of fluids without infection, also known as otitis media with effusion. One cause of this is fluid that stays in the ear after an infection. Other causes include problems with the eustachian tubes or another condition that keeps fluid from draining.

Fluid buildup can cause hearing loss and balance problems. Ear tubes might help with hearing problems that cause a delay in speaking or other learning delays. These delays can cause problems in school.

- Ongoing middle ear infection, also known as chronic middle ear infection. This infection, which is caused by bacteria, doesn't get better with antibiotics. An ear tube can drain the ear and make a way for antibiotic drops to be put right into the middle ear.

- Ongoing inflammation of the middle ear, also known as chronic suppurative otitis media. This inflammation causes a tear in the eardrum and continuing drainage from the ear. An infection, a blocked eustachian tube or injury to the ear can cause the tear. An ear tube can help the ear drain after surgery to fix the eardrum. The tube also makes a way for ear drops to be put right into the middle ear.

Risks

Putting in an ear tube carries a low risk of serious problems. Possible risks include:

- Bleeding and infection.

- Ongoing fluid drainage.

- Blocked tubes from blood or mucus.

- Eardrum scarring or weakening.

- Tubes falling out too soon or staying in too long.

- The eardrum not closing after the tube falls out or is taken out.

Anesthesia

Children who have surgery for ear tube placement usually need medicine that puts them to sleep, also known as general anesthesia. The risks of the medicine are low in healthy children. But possible problems include:

- Upset stomach or throwing up after the surgery.

- Trouble breathing.

- Allergic reaction.

- Irregular heartbeats.

How you prepare

Ask your health care team how to get your child ready for surgery to place ear tubes.

Tell your health care team:

- All medicines your child takes.

- Your child's history or family history of bad reactions to anesthesia.

- Known allergy or other bad reactions to other medicines, such as medicines to fight infections, known as antibiotics.

Questions to ask a member of your health care team:

- When does my child need to start fasting?

- What medicines can my child take before surgery?

- When should we arrive at the hospital?

- Where do we need to check in?

- What is the expected recovery time?

Tips for helping a child prepare include the following:

- Start talking about the hospital visit a few days before the appointment.

- Tell the child that ear tubes can help make ears feel better or make it easier to hear.

- Tell the child about the special medicine putting the child to sleep during the surgery.

- Let the child pick out a favorite comfort toy, such as a blanket or stuffed animal, to take to the hospital.

- Let the child know you'll stay at the hospital while the tubes are being placed.

What you can expect

A surgeon trained in ear, nose and throat conditions places ear tubes during surgery.

Before the procedure

The surgeon usually uses medicine that puts children to sleep for the surgery, also known as general anesthesia.

During the procedure

The procedure usually takes about 15 minutes. The surgeon:

- Makes a tiny hole in the eardrum with a small scalpel or laser.

- Pulls, also called suctions, out fluids from the middle ear.

- Places the tube in the opening in the eardrum.

The team doing the surgery uses tools to watch the child's heart rate, blood pressure and blood oxygen during the surgery.

After the procedure

After surgery, children are moved to a recovery room. The health care team watches for any problems. Children who have no problems usually go home in a few hours.

Children might be sleepy and cranky for the rest of the day. They also might feel like throwing up. Most often, children can go back to their regular activities within 24 hours of the surgery.

Follow-up care

Ask your child's health care provider about follow-up care after ear tubes are in. If there are no problems, care usually includes the following:

- A follow-up appointment in 2 to 4 weeks. Your child's ear, nose and throat care provider makes sure the tubes are in place and working as they should. Your child will have other follow-up appointments with the ear, nose and throat care provider or your child's primary care provider every 4 to 6 months.

- Drops to prevent infection, also known as antibiotics. Children who get these drops need to use all the medicine as directed. That's true even if there's no fluid coming from the ear or other symptoms of infection.

- Hearing test, also known as an audiogram. For children who had hearing loss before getting ear tubes, a health care provider might order a test to check hearing afterward.

- Earplugs. Most children don't need to wear earplugs while swimming or bathing unless a health care provider says to do so.

When to contact your doctor

Reasons to see your child's ear, nose and throat specialist outside of scheduled follow-up appointments include:

- Yellow, brown or bloody discharge from the ear that lasts for more than a week.

- Ongoing pain, hearing problems or balance problems.

Results

Ear tubes often:

- Lower the risk of ear infections.

- Make hearing better.

- Make speech better.

- Help with behavior and sleep problems related to ear infections.

Even with ear tubes, children can get some ear infections.