Overview

Uterine fibroids are common growths of the uterus. They often appear during the years you're usually able to get pregnant and give birth. Uterine fibroids are not cancer, and they almost never turn into cancer. They aren't linked with a higher risk of other types of cancer in the uterus either. They're also called leiomyomas (lie-o-my-O-muhs) or myomas.

Fibroids vary in number and size. You can have a single fibroid or more than one. Some of these growths are too small to see with the eyes. Others can grow to the size of a grapefruit or larger. A fibroid that gets very big can distort the inside and the outside of the uterus. In extreme cases, some fibroids grow large enough to fill the pelvis or stomach area. They can make a person look pregnant.

Many people have uterine fibroids sometime during their lives. But you might not know you have them, because they often cause no symptoms. Your health care professional may just happen to find fibroids during a pelvic exam or pregnancy ultrasound.

Products & Services

Symptoms

Fibroid locations

Fibroid locations

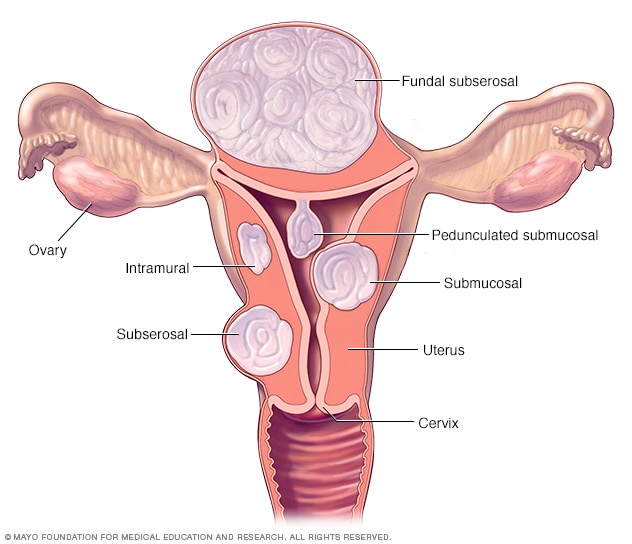

There are three major types of uterine fibroids. Intramural fibroids grow within the muscular uterine wall. Submucosal fibroids bulge into the uterine cavity. Subserosal fibroids project to the outside of the uterus. Some submucosal or subserosal fibroids may be pedunculated. This means they hang from a stalk inside or outside the uterus.

Many people who have uterine fibroids don't have any symptoms. In those who do, symptoms can be influenced by the location, size and number of fibroids.

The most common symptoms of uterine fibroids include:

- Heavy menstrual bleeding or painful periods.

- Longer or more frequent periods.

- Pelvic pressure or pain.

- Frequent urination or trouble urinating.

- Growing stomach area.

- Constipation.

- Pain in the stomach area or lower back, or pain during sex.

Rarely, a fibroid can cause sudden, serious pain when it outgrows its blood supply and starts to die.

Often, fibroids are grouped by their location. Intramural fibroids grow within the muscular wall of the uterus. Submucosal fibroids bulge into the uterine cavity. Subserosal fibroids form on the outside of the uterus.

When to see a doctor

See your doctor if you have:

- Pelvic pain that doesn't go away.

- Heavy or painful periods that limit what you can do.

- Spotting or bleeding between periods.

- Trouble emptying your bladder.

- Ongoing tiredness and weakness, which can be symptoms of anemia, meaning a low level of red blood cells.

Get medical care right away if you have severe bleeding from the vagina or sharp pelvic pain that comes on fast.

Causes

The exact cause of uterine fibroids isn't clear. But these factors may play roles:

- Gene changes. Many fibroids contain changes in genes that differ from those in typical uterine muscle cells.

-

Hormones. Two hormones called estrogen and progesterone cause the tissue the lines the inside of the uterus to thicken during each menstrual cycle to prepare for pregnancy. These hormones also seem to help fibroids grow.

Fibroids contain more cells that estrogen and progesterone bind to than do typical uterine muscle cells. Fibroids tend to shrink after menopause due to a drop in hormone levels.

- Other growth factors. Substances that help the body maintain tissues, such as insulin-like growth factor, may affect fibroid growth.

- Extracellular matrix (ECM). This material makes cells stick together, like mortar between bricks. ECM is increased in fibroids and makes them fibrous. ECM also stores growth factors and causes biologic changes in the cells themselves.

Doctors believe that uterine fibroids may develop from a stem cell in the smooth muscular tissue of the uterus. A single cell divides over and over. In time it turns into a firm, rubbery mass distinct from nearby tissue.

The growth patterns of uterine fibroids vary. They may grow slowly or fast. Or they might stay the same size. Some fibroids go through growth spurts, and some shrink on their own.

Fibroids that form during pregnancy can shrink or go away after pregnancy, as the uterus goes back to its usual size.

Risk factors

There are few known risk factors for uterine fibroids, other than being a person of reproductive age. These include:

- Race. All people of reproductive age who were born female could develop fibroids. But Black people are more likely to have fibroids than are people of other racial groups. Black people have fibroids at younger ages than do white people. They're also likely to have more or larger fibroids, along with worse symptoms, than do white people.

- Family history. If your mother or sister had fibroids, you're at higher risk of getting them.

- Other factors. Starting your period before the age of 10; obesity; being low on vitamin D; having a diet higher in red meat and lower in green vegetables, fruit and dairy; and drinking alcohol, including beer, seem to raise your risk of getting fibroids.

Complications

Uterine fibroids often aren't dangerous. But they can cause pain, and they may lead to complications. These include a drop in red blood cells called anemia. That condition can cause fatigue from heavy blood loss. If you bleed heavily during your period, your doctor may tell you to take an iron supplement to prevent or help manage anemia. Sometimes, a person with anemia needs to receive blood from a donor, called a transfusion, due to blood loss.

Pregnancy and fibroids

Often, fibroids don't interfere with getting pregnant. But some fibroids — especially the submucosal kind — could cause infertility or pregnancy loss.

Fibroids also may raise the risk of certain pregnancy complications. These include:

- Placental abruption, when the organ that brings oxygen and nutrients to the baby, called the placenta, separates from the inner wall of the uterus.

- Fetal growth restriction, when an unborn baby doesn't grow as well as expected.

- Preterm delivery, when a baby is born too early, before the 37th week of pregnancy.

Prevention

Researchers continue to study the causes of fibroid tumors. More research is needed on how to prevent them, though. It might not be possible to prevent uterine fibroids. But only a small percentage of these tumors need treatment.

You might be able to lower your fibroid risk with healthy lifestyle changes. Try to stay at a healthy weight. Get regular exercise. And eat a balanced diet with plenty of fruits and vegetables.

Some research suggests that birth control pills or long-acting progestin-only contraceptives may lower the risk of fibroids. But using birth control pills before the age of 16 may be linked with a higher risk.

Sept. 15, 2023