Diagnosis

Get answers to the most frequently asked questions about prostate cancer from Mayo Clinic urologist Mitchell Humphreys, M.D.

Hello. I'm Dr. Humphreys, a urologist at Mayo Clinic, and I'm here to answer some of the important questions you may have about prostate cancer.

How do you know how fast my cancer is growing?

If you have low to intermediate risk prostate cancer, there are genomic tests that can better inform on the risk of developing a more aggressive cancer. These tests look at the DNA of your actual cancer cells to compare them to other men, to come up with an individual risk profile for you and your cancer. None of it is 100%, but it does provide the best evidence based on your specific prostate cancer.

Is prostate cancer sexually transmitted?

No, there's no risk to your partner from prostate cancer. There's no risk with sexual activity. Prostate cancer is internal and does not spread through contact.

Is prostate cancer hereditary?

Some prostate cancers are hereditary. If you have prostate cancer, all of your first-degree relatives -- parent, sibling, or child -- are at an elevated risk for developing prostate cancer. If you are diagnosed when you're young in your 40s and develop prostate cancer, you may want to consider a genetic consultation to see if there are any known genetic risk factors that you and your family may have.

What can I do to prevent or slow prostate cancer?

There's no one thing. A healthy lifestyle with 30 minutes of exercise a day has shown to be protective. Also, diet is important by limiting red meat and eating fresh fruits and vegetables, low in sugars and carbohydrates. I would advise following a heart-healthy diet as research has shown that it is healthy for the prostate as well.

Is there a risk of cancer spreading if I have a biopsy of my prostate?

No, prostate cancer doesn't spread that way. And there have been millions of biopsies throughout the world and never a single incident of it being spread that way has ever been reported.

When should I stop screening for prostate cancer?

Not all prostate cancer is lethal and not all prostate cancer requires treatment. As a general rule of thumb, if your life expectancy is 10 years or less, you probably will not have to worry about prostate cancer affecting you in your lifetime. However, you should discuss this with your care team to determine how it specifically relates to you.

How can I be the best partner to my medical team?

The best thing you can do is be open and honest. Your medical team is here to be a resource to you, to support you and to help you in any way they can. Never hesitate to ask your medical team any questions or concerns that you have being informed makes all the difference. Thank you for your time and we wish you well.

Prostate cancer diagnosis often starts with an exam and a blood test. A healthcare professional might do these tests as part of prostate cancer screening. Or you might have these tests if you have prostate cancer symptoms. If these first tests detect something concerning, imaging tests can make pictures of the prostate to look for signs of cancer. To be sure whether you have prostate cancer or not, a sample of prostate cells might be removed for testing.

Prostate cancer screening

Prostate cancer screening tests look for prostate cancer in people who don't have any symptoms of the disease. Tests typically include a prostate-specific antigen blood test and a digital rectal exam.

Most experts recommend talking with your healthcare professional about prostate cancer screening around age 50. Together you can decide whether screening is right for you. You might consider starting the discussions sooner if you're a Black person, have a family history of prostate cancer or have other risk factors.

Digital rectal exam

Digital rectal exam

Digital rectal exam

Digital rectal exam

During a digital rectal exam, a healthcare professional inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum. The health professional feels the prostate gland for anything concerning in the texture, shape or size of the gland.

A digital rectal exam lets a healthcare professional examine the prostate. It's sometimes done as part of prostate cancer screening. It might be recommended if your symptoms lead your health professional to think you might have a prostate condition.

During a digital rectal exam, a healthcare professional inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum. The prostate is right by the rectum. The health professional feels the prostate for anything concerning in the texture, shape or size of the gland.

Prostate-specific antigen test

A prostate-specific antigen test is a blood test that measures the amount of prostate-specific antigen in the blood. Prostate-specific antigen, also called PSA, is a substance that prostate cells make. Some PSA circulates in the blood. A PSA test detects the PSA in a blood sample.

Having a high level of PSA in your blood can be a sign of prostate cancer. But many other things also can cause a high PSA level, including prostate infection and prostate enlargement. If a PSA test detects an increased level of PSA in your blood, the test is usually repeated. Your healthcare professional might recommend doing the test again in a few weeks to see if the level goes down. If the level stays high, you might need an imaging test or a biopsy procedure to look for signs of cancer.

A PSA test is often used for prostate cancer screening. It also might be used if you have prostate cancer symptoms. The results can give your healthcare professional clues about your diagnosis.

Prostate ultrasound

Ultrasound is an imaging test that uses sound waves to make pictures of the body. A prostate ultrasound makes pictures of the prostate. A healthcare professional might recommend this test if a digital rectal exam detects something concerning.

To get ultrasound pictures of the prostate, a healthcare professional puts a thin probe into the rectum. The probe uses sound waves to create a picture of the prostate gland. When an ultrasound is done this way, it's called a transrectal ultrasound.

Prostate MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging, also called MRI, uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create pictures of the inside of the body. A prostate MRI makes pictures of the prostate. It's often used to look for concerning areas in the prostate that could be cancer.

Prostate MRI images may help your healthcare team decide whether you should have a biopsy procedure to remove prostate tissue for testing. The prostate MRI images also might help with planning the biopsy. If the MRI detects concerning areas in the prostate, the biopsy can target those areas.

During a prostate MRI, you lie on a table that goes into an MRI machine. Most MRI machines are large, tube-shaped magnets. The magnetic field inside the machine works with radio waves and hydrogen atoms in your body to create cross-sectional images.

Healthcare professionals use different kinds of MRI tests for prostate cancer, including:

- Contrast-enhanced MRI. A contrast-enhanced MRI scan uses a dye to make the pictures clearer. A healthcare professional puts the dye into a vein in your arm before the MRI.

- MRI with endorectal coil. MRI with endorectal coil uses a device inserted in the rectum to get better pictures of the prostate. Before this kind of MRI, a healthcare professional inserts a thin wire into your rectum. This thin wire, called an endorectal coil, sends signals to the MRI machine.

- Multiparametric MRI. A multiparametric MRI, also called mpMRI, tells the healthcare team more about the prostate tissue. This kind of MRI can help show the difference between healthy prostate tissue and prostate cancer.

Prostate biopsy

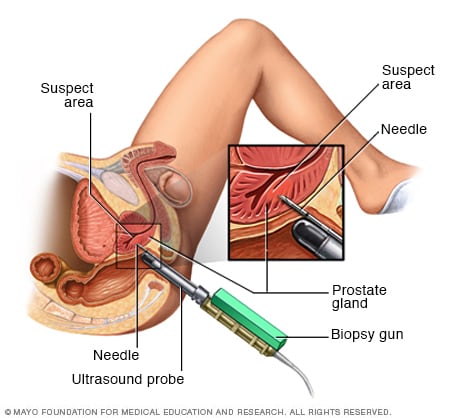

Transrectal biopsy of the prostate

Transrectal biopsy of the prostate

During a transrectal biopsy, a biopsy gun quickly projects a thin needle into suspect areas of the prostate gland, and small sections of tissue are removed for analysis.

A biopsy is a procedure to remove a sample of tissue for testing in a lab. A prostate biopsy involves removing tissue from the prostate. It's the only way to know for sure whether there is cancer in the prostate.

A prostate biopsy involves removing prostate tissue with a needle. The needle can go through the skin or through the rectum to get to the prostate. Your healthcare team chooses the kind of prostate biopsy that's best for you.

Types of prostate biopsy procedures include:

Transrectal prostate biopsy. A transrectal prostate biopsy is a procedure to get a sample of prostate tissue. It involves putting a needle through the wall of the rectum and into the prostate. This is the most common type of prostate biopsy.

During this procedure, a healthcare professional inserts a thin probe into the rectum. The probe makes ultrasound pictures of the rectum. The probe also holds a needle. A healthcare professional uses the ultrasound images to guide the needle. The needle goes through the rectum and into the prostate to remove tissue samples. Samples are removed from different parts of the prostate.

Perineal prostate biopsy. A perineal prostate biopsy is a procedure to get a sample of prostate tissue. It involves putting a needle through the perineum and into the prostate. The perineum is the area of skin between the scrotum and the anus. This kind of prostate biopsy is less common.

During this procedure, a healthcare professional uses an imaging test to help guide the needle. Often this imaging test is an ultrasound. The health professional uses the needle to remove tissue from different parts of the prostate.

Prostate tissue samples go to a lab for testing. In the lab, tests can show whether samples contain cancer.

Prostate biopsy carries a risk of bleeding. Other side effects include blood in the urine and blood in the semen. Sometimes a prostate biopsy causes difficulty urinating or an infection. Side effects may depend on the procedure you have. Ask your healthcare team what you can expect as you recover.

Gleason score and grade group

The Gleason score and grade group are numbers that tell your healthcare team whether your prostate cancer is growing slowly or quickly. How quickly a cancer grows also is called a cancer's grade.

To decide on the grade, doctors in the lab, called pathologists, look at the prostate cancer cells from a prostate biopsy. If the cancer cells look similar to healthy cells, then the cancer cells are low grade. Low-grade cancer grows slowly. If the cancer cells look very different from healthy cells, then the cancer cells are high grade. High-grade cancer grows quickly.

Prostate cancer grades range from 1 to 5. Grade 1 is very low grade and grade 5 is very high grade. To get the Gleason score, pathologists look at all the prostate biopsy samples to find the grade of each one. They figure out the most common grade found in the samples and the second most common grade. They add these two numbers together to get the Gleason score.

Gleason scores can range from 2 to 10. A score that's 5 or lower isn't considered cancer. Gleason scores from 6 to 10 are considered cancer. A Gleason score of 6 means the cancer is growing slowly. A Gleason score of 10 means the cancer is growing quickly.

Pathologists also report the prostate cancer grade as a group. The grade group is another way of stating how quickly the cancer cells are growing. The grade groups for prostate cancer are:

- Grade group 1. This means the Gleason score is 6 or less.

- Grade group 2. This means the Gleason score is 7. The most common grade in the prostate biopsy samples is 3. The second most common grade is 4.

- Grade group 3. This means the Gleason score is 7. The most common grade in the prostate biopsy samples is 4. The second most common grade is 3.

- Grade group 4. This means the Gleason score is 8.

- Grade group 5. This means the Gleason score is 9 or 10.

Your healthcare team uses your grade group to decide on your cancer's stage. The grade group also can help your care team plan your treatment.

Prostate cancer biomarker tests

Biomarkers are things that can be detected in the body. Results from biomarker tests tell healthcare professionals about what's going on inside the body. Biomarker testing for cancer looks for biomarkers in the cancer cells. The results help healthcare professionals learn more about what's going on inside the cancer cells.

Healthcare professionals use prostate cancer biomarker tests to:

- Decide whether to do a prostate biopsy. Some prostate cancer biomarker tests use blood and urine samples to detect signals made by prostate cancer cells. The tests can tell your healthcare team whether a prostate biopsy is likely or not likely to find prostate cancer.

- Decide on a treatment for early prostate cancer. Some prostate cancer biomarker tests involve testing the cancer cells to see if the cancer has a high risk or a low risk of spreading beyond the prostate. If the results of other tests haven't been clear, this kind of test might help your care team understand your risk. The results can help decide between starting treatment right away or watching the cancer closely to see if it grows.

- Decide on a treatment for advanced prostate cancer. Other prostate cancer biomarker tests help when the cancer is advanced. For prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, the results of these tests can tell your healthcare team whether certain treatments are likely to work on your cancer cells. For this kind of test, your healthcare team may test some of the cells that have spread. The cells might be removed with a biopsy procedure or collected from a blood sample.

Not everyone needs a prostate cancer biomarker test. These tests are new, and healthcare professionals are still deciding how best to use them.

Imaging tests to look for prostate cancer that has spread

Imaging tests can look for signs that the cancer has spread beyond the prostate. These tests might detect cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or to other parts of the body.

Most people with prostate cancer only have cancer in the prostate. They might not need these other imaging tests to look for signs of cancer spread. Ask your healthcare team whether you need these imaging tests.

When prostate cancer spreads beyond the prostate, it might be called metastatic prostate cancer, stage 4 prostate cancer or advanced prostate cancer. Imaging tests used to detect this kind of prostate cancer include:

- A bone scan. A bone scan uses nuclear imaging to make pictures. Nuclear imaging involves using small amounts of radioactive substances, called radioactive tracers. A special camera that can detect the radioactivity also is used along with a computer. The tracer is absorbed more by cells and tissues that are changing. Cancer cells are often growing and changing quickly. Bone scan images can detect places in the bones that absorb the tracer. These may be signs of prostate cancer in the bones.

- A computerized tomography scan. A computerized tomography scan, also called a CT scan, is a type of imaging that uses X-ray techniques to create detailed images of the body. It then uses a computer to create cross-sectional images, also called slices, of the bones, blood vessels and soft tissues inside the body. A CT scan can detect prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or other places in the body.

- Magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging, also called MRI, uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create pictures of the inside of the body. An MRI can detect prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or other places in the body.

- A positron emission tomography scan. A positron emission tomography scan, also called a PET scan, is a nuclear imaging test. It uses a radioactive tracer that's injected into a vein. The tracer contains a substance that helps it stick to fast-growing cells, such as cancer cells. The PET images show the places where the tracer builds up. A PET scan can detect prostate cancer that has spread to other places in the body.

- A prostate-specific membrane antigen PET scan. A prostate-specific membrane antigen PET scan also is called a PSMA PET scan. Like other PET scans, this test uses a radioactive tracer. The tracer contains a substance that helps the tracer stick to prostate cancer cells. The substance attaches to a protein that's found on the surface of prostate cancer cells. A PSMA PET scan can detect prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or other places in the body.

Prostate cancer stages

Your healthcare team uses the results of your tests and procedures to give your cancer a stage. The cancer's stage tells your healthcare team about the size of the cancer and how quickly it's growing.

To decide your prostate cancer stage, your healthcare team uses these factors:

- How much of the prostate contains cancer.

- Whether the cancer has grown beyond the prostate, such as into the rectum, bladder or other nearby areas.

- Whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

- Whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones.

- The level of PSA in the blood.

- The grade group.

Prostate cancer stages range from 1 to 4. A lower number means the cancer is small and only in the prostate. A lower number stage typically means the cancer is very likely to be cured. If the cancer grows larger or spreads, the stage goes up. A higher number stage may mean a cure is less likely. Your prognosis depends on many factors, so talk about this with your healthcare team.

The stages of prostate cancer are:

- Stage 1 prostate cancer. A stage 1 prostate cancer means the cancer is small and only in the prostate. The cancer only affects one side of the prostate gland. The PSA level is low and the grade group is 1.

- Stage 2A prostate cancer. A stage 2A prostate cancer may be a small cancer that only affects one side of the prostate, but the PSA level is intermediate. This stage also can mean that the cancer affects both sides of the prostate, but the PSA level is low. At this stage, the grade group is 1.

- Stage 2B prostate cancer. A stage 2B prostate cancer is only in the prostate. The cancer may have grown to involve both sides of the prostate gland. At this stage, the PSA level is intermediate. The grade group is 2.

- Stage 2C prostate cancer. A stage 2C prostate cancer is only in the prostate. The cancer may have grown to involve both sides of the prostate gland. The PSA level is intermediate. The grade group is 3 or 4.

- Stage 3A prostate cancer. A stage 3A prostate cancer is only in the prostate. The cancer may have grown to involve both sides of the prostate gland. The PSA level is high. This stage includes grade groups 1 to 4.

- Stage 3B prostate cancer. A stage 3B prostate cancer has grown beyond the prostate. The cancer might extend to the seminal vesicles, bladder, rectum or other nearby organs. The PSA level may be low, intermediate or high. This stage includes grade groups 1 to 4.

- Stage 3C prostate cancer. A stage 3C prostate cancer has a grade group of 5. It includes any size prostate cancer. The cancer may have grown beyond the prostate, but it hasn't spread yet.

- Stage 4A prostate cancer. A stage 4A prostate cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

- Stage 4B prostate cancer. A stage 4B prostate cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones.

Prostate cancer prognosis

The cancer prognosis tells you how likely it is that the cancer can be cured. Your healthcare team can get a general sense of your outlook using your prostate cancer stage. But the stage can't tell your future. Your personal prognosis may depend on:

- Your age.

- Your overall health.

- The cancer's stage.

- PSA test results.

- Prostate biopsy results.

- Grade group.

Talk with your healthcare team about your prognosis if you want to know what to expect. Your healthcare team can explain what they consider when thinking about your prognosis.

Prostate cancer survival rates

The chance of surviving prostate cancer is quite good for most people. To understand prostate cancer survival rates, experts study many people with prostate cancer to see how many are living five years after their diagnosis.

When the cancer is only in the prostate, the chance of surviving at least five years is 100%. As the cancer spreads beyond the prostate, the chances get lower. When prostate cancer has spread to other parts of the body, called metastatic prostate cancer, the chances of surviving at least five years is about 37%.

Keep in mind that survival statistics take five years to collect. The most recent survival rates include people who had prostate cancer treatment more than five years ago. These people may not have had access to the latest treatments. Over the last few decades, prostate cancer death rates have been falling and survival rates have been increasing.

More Information

Treatment

Prostate cancer treatments include surgery, radiation therapy and medicines. Medicines for prostate cancer include hormone therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Sometimes other treatments are used to treat prostate cancer. These might include having ablation therapy with heat or cold to hurt the cancer cells and receiving medicine that gives radiation directly to the cancer cells.

Your healthcare team considers many things when creating your prostate cancer treatment plan. They consider the size of your cancer, whether it has spread and how quickly it's growing. They also consider your overall health and your preferences. Talk with your healthcare team about your options.

Active surveillance for prostate cancer

Prostate cancer treatment isn't always needed right away. Instead, the healthcare team may watch the cancer closely. Healthcare professionals call this active surveillance. It often involves regular follow-up blood tests, imaging tests and prostate biopsies. If tests show that the cancer is growing, you may choose to start treatment. For some prostate cancers, treatment may never be needed.

Active surveillance may be an option for prostate cancer that doesn't cause symptoms and is expected to grow very slowly. Active surveillance may be right for someone who has another serious health condition that makes cancer treatment more difficult.

Surgery for prostate cancer

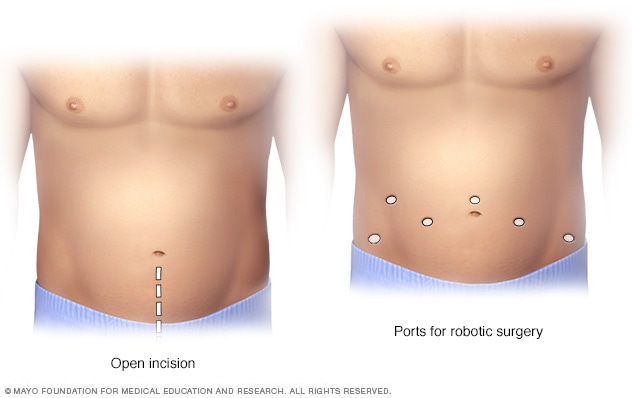

Prostatectomy incisions

Prostatectomy incisions

During an open prostatectomy, one large incision is made in the lower stomach area (left). During a robotic prostatectomy, several smaller incisions are made in the stomach area (right).

Surgery for prostate cancer most often involves removing the prostate. Surgery to remove the prostate is called prostatectomy. It's often used when the cancer is only in the prostate. Sometimes it can treat a cancer that grows larger or spreads to the lymph nodes.

There are many ways of doing a prostatectomy for prostate cancer, including:

- Laparoscopic prostatectomy. During a laparoscopic prostatectomy for prostate cancer, a surgeon makes several small cuts in the belly. The surgeon puts surgical tools through the cuts. The surgeon uses the tools to remove the prostate.

- Robotic prostatectomy. During a robotic prostatectomy for prostate cancer, a surgeon uses hand controls to guide robotic arms. The arms hold the surgical tools. The surgeon sits at a console to use the hand controls that move the robotic arms. Just like in a laparoscopic prostatectomy, the surgeon makes several small cuts in the belly. The surgeon guides the robotic arms to put surgical tools through the cuts in the belly to remove the prostate. Most prostate cancer operations use robotic prostatectomy.

- Open prostatectomy. During open prostatectomy for prostate cancer, a surgeon makes one large cut in the lower belly. The surgeon removes the prostate through this large cut. This procedure also is called retropubic prostatectomy. This way of doing prostate cancer surgery is not very common. But it might be the right choice in some situations.

Prostate cancer surgery carries a risk of bleeding, infection, pain and blood clots. If they happen, these complications tend to occur soon after surgery. Laparoscopic prostatectomy and robotic prostatectomy tend to have a lower risk of these side effects.

Long term, prostate cancer surgery can cause leaking urine, called urinary incontinence. It also can cause difficulty getting an erection, called erectile dysfunction. These side effects usually get better over time.

External beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer

External beam radiation for prostate cancer

External beam radiation for prostate cancer

During external beam radiation treatment for prostate cancer, you lie on a table while a linear accelerator moves around you to deliver radiation from many angles. The linear accelerator delivers the precise dose of radiation planned by your treatment team.

Radiation therapy treats cancer with powerful energy beams. External beam radiation is one type of radiation therapy used for prostate cancer. It involves using a machine to aim beams of radiation at the body.

During external beam radiation therapy, you lie on a table while a machine moves around your body. The machine directs powerful energy beams to the prostate cancer. The beams can be made of X-rays, protons or other types of energy.

You typically have external beam radiation treatments five days a week for several weeks. Some medical centers offer shorter radiation therapy treatment schedules. This approach uses a similar dose of radiation but spreads the dose over fewer days. Some radiation therapy treatments happen over a few days.

Healthcare professionals use external beam radiation to treat cancer that's only in the prostate. For a small prostate cancer, it might be the only treatment needed.

Sometimes healthcare professionals recommend external beam radiation after surgery. The radiation can help kill any cancer cells that might remain. It can lower the risk that the cancer could spread or come back.

External beam radiation also helps with advanced prostate cancer. When the cancer spreads to other parts of the body, such as the bones, the radiation can slow the cancer's growth. Radiation also can help with symptoms, such as pain.

External beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer can cause side effects such as irritation of the intestines. This can cause diarrhea, bloody stool and a feeling that the bowel can't be emptied completely. Other side effects include frequent urination, painful urination and difficulty starting urination. After treatment, there also can be difficulty getting an erection.

Brachytherapy for prostate cancer

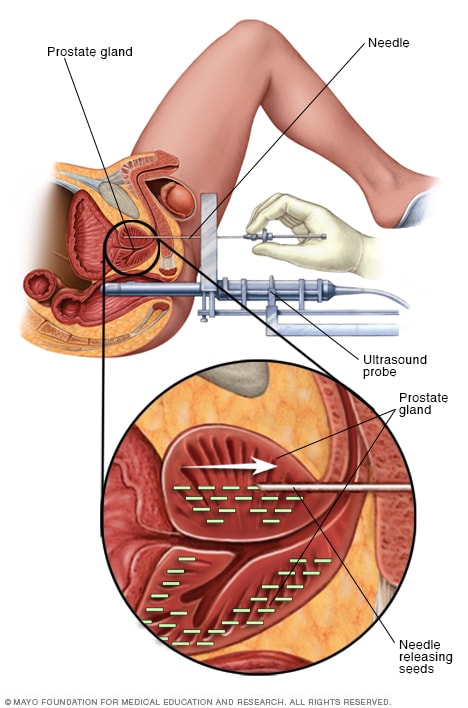

Permanent prostate brachytherapy

Permanent prostate brachytherapy

Permanent prostate brachytherapy involves placing many radioactive seeds within the prostate to treat prostate cancer. During the procedure, an ultrasound probe is placed in the rectum to help guide the placement of seeds. The seeds emit radiation that dissipates over a few months.

Brachytherapy involves placing radiation inside the body. Brachytherapy is one type of radiation therapy used to treat prostate cancer.

Most prostate cancer brachytherapy treatments are permanent. Permanent brachytherapy is sometimes called low dose rate brachytherapy. This treatment uses rice-sized seeds that contain radioactive material. A healthcare professional uses a device to insert the seeds into the prostate gland. The seeds slowly give off a low dose of radiation over time.

Sometimes prostate cancer brachytherapy treatments are temporary. Temporary brachytherapy is sometimes called high dose rate brachytherapy. This treatment involves placing radioactive material in the prostate for a short period. Then the radioactive material is removed. The treatment might repeat over multiple days.

Healthcare professionals use brachytherapy to treat prostate cancer that's only in the prostate. Brachytherapy doesn't treat cancer that has spread to other parts of the body.

Side effects of brachytherapy for prostate cancer include frequent urination, painful urination and blood in the urine. There may be diarrhea, constipation and a feeling that the bowel can't be emptied completely. There also can be difficulty getting an erection.

Ablation therapy for prostate cancer

Ablation is a procedure that applies treatment directly to the cancer cells in order to hurt them. It's not a standard treatment for prostate cancer but is used in some situations. Types of ablation therapy used for prostate cancer include:

- Cryoablation for prostate cancer. Cryoablation uses cold to hurt cancer cells. It's also called cryotherapy. To treat prostate cancer, a healthcare professional inserts thin needles through the skin of the perineum. The needles go through the skin and into the prostate. The health professional uses a machine to cool down the needles. This causes the tissue around the needles to freeze. The health professional carefully controls how much of the prostate gets the freezing treatment. Then the health professional allows the tissue to thaw. The freezing and thawing hurts the cancer cells.

- High-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer. High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment, also called HIFU, uses heat to hurt the cancer cells. The heat comes from high-intensity sound waves, called ultrasound waves. To treat the prostate, a healthcare professional inserts a thin probe into the rectum. The probe sends out ultrasound waves to the prostate. This causes the tissue to heat up to a temperature that hurts the cancer cells.

Healthcare professionals sometimes use ablation therapy to treat very small prostate cancers. It might be used when surgery isn't possible. For example, ablation may be the best choice if other health conditions make surgery and other treatments risky.

Healthcare professionals sometimes use ablation therapy if the cancer comes back. It might help treat prostate cancer that comes back after radiation therapy.

Ablation therapy side effects include pain and swelling in the treatment area and difficulty getting an erection. Sometimes the treatment can hurt the bladder or the tube that carries urine out of the bladder, called the urethra. This may lead to using urinary catheters to help with urination.

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer is a treatment that stops the hormone testosterone either from being made or from reaching prostate cancer cells. Prostate cancer cells rely on testosterone to help them grow. Cutting off the supply of testosterone may cause cancer cells to die or to grow more slowly.

Hormone therapy treatments for prostate cancer include:

- Medicines that stop the testicles from making testosterone. Some medicines stop cells from getting the signals that tell them to make testosterone. These medicines are called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists. Another name for these medicines is LHRH agonists and antagonists. Medicines that work in this way include goserelin (Zoladex) and degarelix (Firmagon), among many others.

- Medicines that stop testosterone from acting on cancer cells. These medicines, known as antiandrogens, are often used with LHRH agonists. That's because LHRH agonists can cause a brief rise in testosterone levels before testosterone levels go down. Medicines that work in this way include bicalutamide (Casodex) and nilutamide (Nilandron), among many others.

- Surgery to remove the testicles, called orchiectomy. Surgery to remove both testicles lowers testosterone levels in the body quickly.

Hormone therapy is often used to treat prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or to other parts of the body. Hormone therapy can shrink the cancer and slow its growth.

Hormone therapy is sometimes used with radiation therapy to treat cancer that hasn't spread beyond the prostate. It helps make the radiation therapy more effective.

Side effects of prostate cancer hormone therapy include hot flashes, trouble sleeping, loss of muscle and increase in body fat. There may be a loss of sex drive, and it can be more difficult to get an erection. Other hormone therapy risks include an increased chance of getting diabetes and heart disease.

Chemotherapy for prostate cancer

Chemotherapy treats cancer with strong medicines. Chemotherapy medicines are sometimes used with hormone therapy medicines for prostate cancer. Healthcare professionals sometimes use these medicines together for advanced prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or to other parts of the body. Chemotherapy also helps treat advanced prostate cancer when hormone therapy isn't working.

Chemotherapy medicines commonly used for prostate cancer include docetaxel (Beizray, Docivyx, Taxotere) and cabazitaxel (Jevtana). A healthcare professional gives these medicines through a vein. The treatments typically happen once every three weeks. Side effects of these medicines include feeling very tired, easy bruising and more-frequent infections. They also can damage the nerves in the fingers and toes, called peripheral neuropathy. This can cause numbness and tingling in the fingers and toes.

Other chemotherapy medicines exist. Your healthcare team picks the best medicines for your cancer.

Targeted therapy for prostate cancer

Targeted therapy for cancer is a treatment that uses medicines that attack specific chemicals in the cancer cells. By blocking these chemicals, targeted treatments can cause cancer cells to die.

For prostate cancer, targeted therapy medicines can help treat cancer that spreads or that comes back after other treatments. Healthcare teams often give targeted therapy medicines with hormone therapy medicines. Sometimes targeted therapy medicines are used alone.

Many targeted therapy medicines exist. Targeted therapy medicines sometimes used for prostate cancer include:

- Niraparib (Zejula).

- Olaparib (Lynparza).

- Rucaparib (Rubraca).

- Talazoparib (Talzenna).

These targeted therapy medicines come as a pill or capsule you swallow. The medicines block the action of enzymes in the cancer cells that help repair breaks in the DNA. These targeted therapy medicines only work in people with certain DNA changes in their cells. To find out if these changes are present in your cells, your healthcare team may test your blood or some of your cancer cells.

Side effects of targeted therapy medicines for prostate cancer include feeling very tired, nausea and loss of appetite. Other side effects include diarrhea, cough, easy bruising and more-frequent infections.

Immunotherapy for prostate cancer

Immunotherapy for cancer is a treatment with medicine that helps the body's immune system kill cancer cells. The immune system fights off diseases by attacking germs and other cells that shouldn't be in the body. Cancer cells survive by hiding from the immune system. Immunotherapy helps the immune system cells find and kill the cancer cells.

Prostate cancer immunotherapy can involve:

- Cell therapy for prostate cancer. Cell therapy is a treatment that trains immune system cells to find and stop cancer cells. It involves taking some of your immune system cells from your blood. The cells go to a lab where they get treatment that helps them find prostate cancer cells. The treated cells are put back in your body where they can fight the cancer. One treatment that works in this way is sipuleucel-T (Provenge). It can cause flu-like side effects, such as fever, chills and headache.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors for prostate cancer. Immunotherapy medicines called immune checkpoint inhibitors help immune system cells find cancer cells. Some cells can send signals called immune checkpoints to the immune system. Immune checkpoints tell the immune system cells not to attack. Usually, immune checkpoints help keep the immune system from hurting healthy cells. But some cancer cells also send these signals. Immune checkpoint inhibitor medicines stop cancer cells from sending the signals to not attack.

These medicines only work in people with cancer cells that have certain DNA changes. Most prostate cancers don't respond to this treatment. One example of an immune checkpoint inhibitor used for prostate cancer is pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Side effects can include feeling very tired, itchy skin, diarrhea, loss of appetite and rash. Sometimes this treatment causes the immune system to attack the organs, leading to serious complications.

Healthcare professionals sometimes use prostate cancer immunotherapy treatments for cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, called metastatic prostate cancer.

Radiopharmaceutical treatments for prostate cancer

Radiopharmaceutical treatments are medicines that contain a radioactive substance. Radiopharmaceutical treatments used for cancer can deliver radiation to cancer cells.

For prostate cancer, radiopharmaceutical treatments are typically used when the cancer is advanced. People with stage 4 prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, also called metastatic prostate cancer, might consider radiopharmaceutical treatments.

Radiopharmaceuticals used for prostate cancer include:

- Treatments that target PSMA. Radiopharmaceutical treatments can target a protein that's common on prostate cancer cells called prostate-specific membrane antigen. It's also called PSMA. One radiopharmaceutical medicine that works in this way is lutetium Lu-177 vipivotide tetraxetan (Pluvicto). This medicine contains a molecule that finds and sticks to the PSMA on prostate cancer cells. The medicine also contains a radioactive substance. A healthcare professional gives this medicine through a vein. The medicine finds the prostate cancer cells and releases the radiation directly into the cells. PSMA therapy can treat prostate cancer anywhere in the body. This treatment only works if the prostate cancer cells make the PSMA protein. Side effects include dry mouth, nausea and feeling very tired.

- Treatments that target the bones. Some radiopharmaceutical medicines contain a radioactive substance that is attracted to bones. When a healthcare professional puts this medicine into a vein, it travels to the bones and releases the radiation. One medicine that works in this way is radium Ra-223 (Xofigo). Healthcare professionals sometimes use it when prostate cancer spreads to the bones but not to other parts of the body. This treatment can help with bone pain and other symptoms. Side effects include diarrhea and feeling very tired.

More Information

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Alternative medicine

No complementary or alternative treatments will cure prostate cancer. However, complementary and alternative prostate cancer treatments may help you cope with the side effects of cancer and its treatment.

Many people with cancer experience distress at some point. If you're distressed, you may feel sad, angry or anxious. You may have difficulty sleeping or find yourself constantly thinking about your cancer.

Several complementary medicine techniques may help you cope with distress, including:

- Art therapy.

- Dance or movement therapy.

- Exercise.

- Meditation.

- Music therapy.

- Relaxation techniques.

- Spiritual practices.

Talk with your healthcare team if you're feeling distress. Some things that cause distress are treated with medicines and other treatments. If you're interested in trying complementary treatments, talk about them with your healthcare team to make sure they are safe for you.

Coping and support

When you receive a diagnosis of prostate cancer, you may experience a range of feelings. People with prostate cancer sometimes describe feeling disbelief, fear, anger and sadness. With time, each person figures out a way to cope with a prostate cancer diagnosis. Until you find what works for you, here are some ways of coping that you can try.

- Learn enough to feel comfortable making treatment decisions. Learn as much as you need to know about your prostate cancer and its treatment to understand what to expect from treatment and life after treatment. Ask your doctor, nurse or other healthcare professional to recommend some good sources of information to get you started.

- Find a good listener. Finding someone who is willing to listen to you talk about your hopes and fears can be helpful as you manage a cancer diagnosis. This could be a friend or family member. A counselor, medical social worker or clergy member also may offer helpful guidance and care.

- Connect with other cancer survivors. Other people with prostate cancer sometimes are best at knowing what you're going through. They can provide a unique network of support. Ask your healthcare team about support groups or community organizations that can connect you with other people with cancer. In the United States, contact the American Cancer Society for information about support groups.

- Take care of yourself. Take care of yourself during cancer treatment by eating a diet full of fruits and vegetables. Try to exercise most days of the week. Get enough sleep each night so that you wake feeling rested.

- Continue sexual expression. If you experience erectile dysfunction, continue to stay close with your partner in other ways. For some people with erectile dysfunction, a natural reaction may be to avoid all sexual contact. But consider touching, holding, hugging and caressing as ways to continue sharing sexuality with your partner.

Preparing for your appointment

If you have symptoms that worry you, start by making an appointment with a doctor or other healthcare professional.

If your doctor suspects that you may have a prostate condition, you may be referred to a doctor who treats urinary tract conditions. This doctor is called a urologist. If you're diagnosed with prostate cancer, you may be referred to a cancer doctor, called an oncologist. You also might meet with a doctor who uses radiation therapy to treat cancer. This doctor is called a radiation oncologist.

Because appointments can be brief, it's a good idea to be prepared. Here's some information to help you get ready.

What you can do

- Be aware of any restrictions. At the time you make the appointment, be sure to ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet.

- Write down any symptoms, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins and supplements that you're taking.

- Consider taking a family member or friend along. Sometimes it can be difficult to remember all the information you get during an appointment. Someone who goes with you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your healthcare professional.

Some questions to ask about prostate cancer include:

- Do I have prostate cancer?

- How large is my prostate cancer?

- Has my prostate cancer spread beyond my prostate?

- What's my Gleason score?

- What's my prostate-specific antigen level?

- Will I need more tests?

- What are my treatment options?

- Is there one treatment option you think is best for me?

- Do I need cancer treatment right away, or is it possible to wait and see if the cancer grows?

- What are the potential side effects of each treatment?

- What is the chance that my prostate cancer will be cured with treatment?

- If you had a friend or family member in my situation, what would you recommend?

- Should I see a specialist? What will that cost, and will my insurance cover it?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared, don't hesitate to ask other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare team may ask questions about your symptoms and your health history. Be ready to answer questions such as:

- When did you first begin having symptoms?

- Have your symptoms stayed or do they come and go?

- How bad are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to make your symptoms better?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

Feb. 20, 2025