Overview

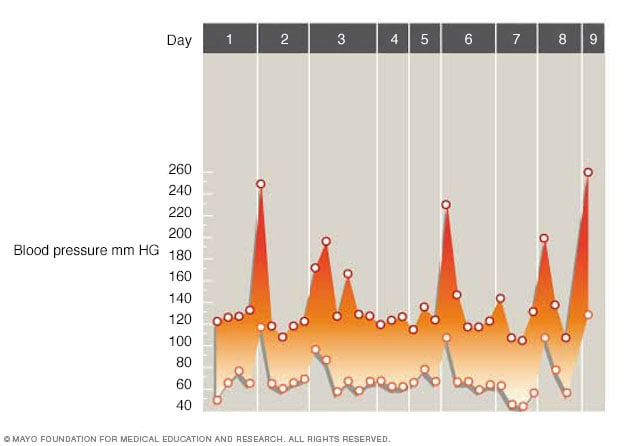

Pheochromocytoma and irregular blood pressure

Pheochromocytoma and irregular blood pressure

A pheochromocytoma can cause large changes in blood pressure. When that happens, it's called a spell. Blood pressure may return to a healthy range between spells. That can make it harder to diagnose a pheochromocytoma. The graph shows a nine-day period of short, irregular bursts in blood pressure due to a pheochromocytoma. The lower points show the bottom number of the reading, called diastolic pressure. The higher points show the top number of the reading, called systolic pressure. For example, the first burst in blood pressure is seen on day two with a reading of 250/110 millimeters of mercury.

A pheochromocytoma (fee-o-kroe-moe-sy-TOE-muh) is a rare tumor that grows in an adrenal gland. Most often, the tumor is not cancer. When a tumor isn't cancer, it's called benign.

You have two adrenal glands — one at the top of each kidney. The adrenal glands make hormones that help control key processes in the body, such as blood pressure. Usually, a pheochromocytoma forms in only one adrenal gland. But tumors can grow in both adrenal glands.

With a pheochromocytoma, the tumor releases hormones that can cause various symptoms. They include high blood pressure, headache, sweating and symptoms of a panic attack. If a pheochromocytoma isn't treated, serious or life-threatening damage to other body systems can happen.

Surgery to remove a pheochromocytoma often returns blood pressure to a healthy range.

Products & Services

Symptoms

A pheochromocytoma often causes the following symptoms:

- High blood pressure.

- Headache.

- Heavy sweating.

- Rapid heartbeat.

Some people with pheochromocytomas also have symptoms such as:

- Nervous shaking.

- Skin that turns a lighter color, also called pallor.

- Shortness of breath.

- Panic attack-type symptoms, which can include sudden intense fear.

- Anxiety or a sense of doom.

- Vision problems.

- Constipation.

- Weight loss.

Some people with pheochromocytomas have no symptoms. They don't realize they have the tumor until an imaging test happens to find it.

Symptom spells

Most often, the symptoms of pheochromocytoma come and go. When they start suddenly and keep coming back, they're known as spells or attacks. These spells may or may not have a trigger that can be found.

Certain activities or conditions can lead to a spell, such as:

- Physical hard work.

- Anxiety or stress.

- Changes in body position, such as bending over, or going from sitting or lying down to standing.

- Labor and delivery.

- Surgery and a medicine that causes you to be in a sleep-like state during surgery, called an anesthetic.

Foods high in tyramine, a substance that affects blood pressure, also can trigger spells. Tyramine is common in foods that are fermented, aged, pickled, cured, overripe or spoiled. These foods include:

- Some cheeses.

- Some beers and wines.

- Soybeans or products made with soy.

- Chocolate.

- Dried or smoked meats.

Certain medicines and drugs that can trigger spells include:

- Depression medicines called tricyclic antidepressants. Some examples of tricyclic antidepressants are amitriptyline and desipramine (Norpramin).

- Depression medicines called monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), such as phenelzine (Nardil), tranylcypromine (Parnate) and isocarboxazid (Marplan). The risk of spells is even higher if these medicines are taken with foods or drinks high in tyramine.

- Stimulants such as caffeine, amphetamines or cocaine.

When to see a doctor

High blood pressure is one of the main symptoms of a pheochromocytoma. But most people who have high blood pressure don't have an adrenal tumor. Talk to your healthcare professional if any of these factors apply to you:

- Spells of symptoms linked with pheochromocytoma, such as headaches, sweating and a fast, pounding heartbeat.

- Trouble controlling high blood pressure with your current treatment.

- High blood pressure that starts before the age of 20.

- Recurring large rises in blood pressure.

- A family history of pheochromocytoma.

- A family history of a related genetic condition. These include multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2 (MEN 2), von Hippel-Lindau disease, inherited paraganglioma syndromes and neurofibromatosis 1.

Causes

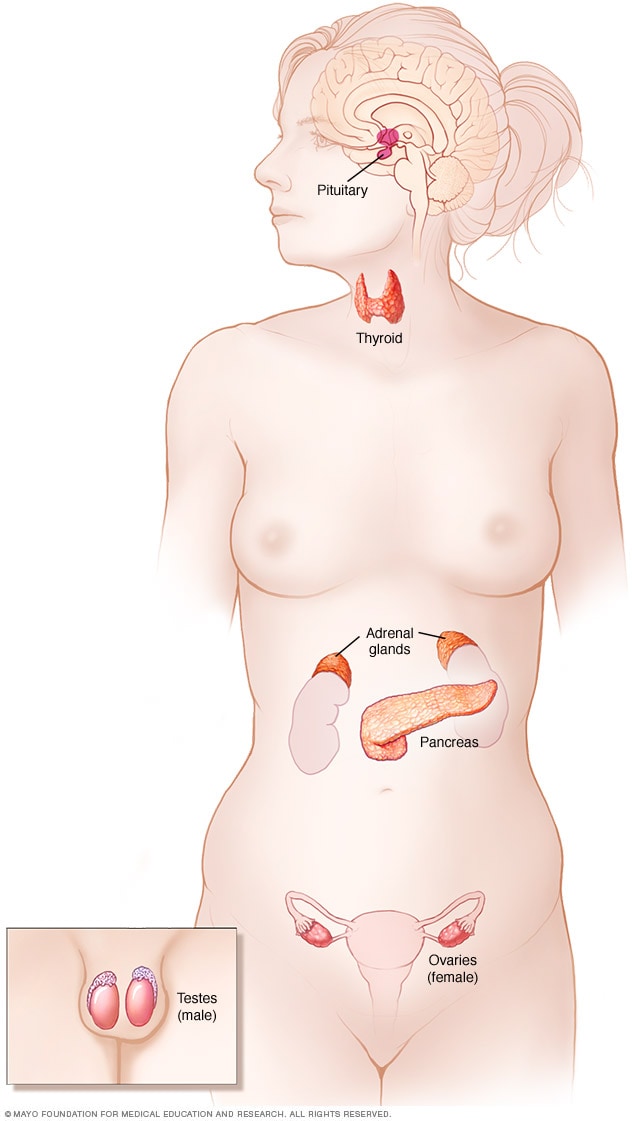

Endocrine system

Endocrine system

The endocrine system is made up of glands and organs that make hormones. The endocrine system includes the pituitary gland, thyroid gland, parathyroid glands, adrenal glands, pancreas, ovaries and testicles.

Researchers don't know exactly what causes a pheochromocytoma. The tumor forms in cells called chromaffin cells. These cells are located in the center of an adrenal gland. They release certain hormones, mainly adrenaline and noradrenaline. These hormones help control many body functions, such as heart rate, blood pressure and blood sugar.

Adrenaline and noradrenaline trigger the body's fight-or-flight response. That response happens when the body thinks there is a threat. The hormones cause blood pressure to rise and the heart to beat faster. They also prepare other body systems so you can react quickly. A pheochromocytoma causes more of these hormones to be released. And it causes them to be released when you're not in a threatening situation.

Most of the chromaffin cells are in the adrenal glands. But small clusters of these cells also are in the heart, head, neck, bladder, stomach area and along the spine. Chromaffin cell tumors located outside of the adrenal glands are called paragangliomas. They may cause the same effects on the body as a pheochromocytoma.

Risk factors

Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2B (MEN 2B)

Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2B (MEN 2B)

People with MEN 2B have tumors of nerves in the lips, mouth, eyes and digestive tract. They also may have a tumor on the adrenal gland, called pheochromocytoma, and medullary thyroid cancer.

A person's age and certain medical conditions can raise the risk of a pheochromocytoma.

Most pheochromocytomas are found in people between the ages of 20 and 50. But the tumor can form at any age.

People who have certain rare genetic conditions have a higher risk of pheochromocytomas. The tumors can be benign, meaning they are not cancer. Or they can be malignant, meaning they are cancer. Often, benign tumors related to these genetic conditions form in both adrenal glands. Genetic conditions linked with pheochromocytoma include:

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2 (MEN 2). This condition can cause tumors in more than one part of the body's hormone-making system, called the endocrine system. There are two types of MEN 2 — type 2A and type 2B. Both can involve pheochromocytomas. Other tumors linked with this condition can appear in other parts of the body. These body parts include the thyroid, parathyroid glands, lips, mouth and digestive system.

- Von Hippel-Lindau disease. This condition can cause tumors in many parts of the body. Possible sites include the brain and spinal cord, endocrine system, pancreas and kidneys.

- Neurofibromatosis 1. This condition causes tumors in the skin called neurofibromas. It also can cause tumors of the nerve at the back of the eye that connects to the brain, called the optic nerve.

- Hereditary paraganglioma syndromes. These conditions are passed down in families. They can result in pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas.

Complications

A pheochromocytoma can lead to other health problems. The high blood pressure linked with a pheochromocytoma can damage organs, especially tissues of the heart and blood vessel system, brain and kidneys. This damage can cause dangerous conditions, including:

- Heart disease.

- Stroke.

- Kidney failure.

- Vision loss.

Cancerous tumors

Rarely, a pheochromocytoma is cancerous, and the cancer cells spread to other parts of the body. Cancer cells from a pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma most often travel to the lymph system, bones, liver or lungs.