Overview

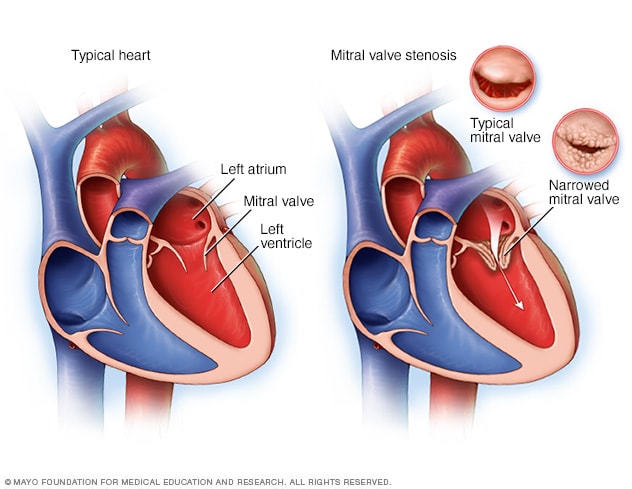

Typical heart and heart with mitral valve stenosis

Typical heart and heart with mitral valve stenosis

Mitral valve stenosis, shown in the heart on the right, is a condition in which the heart's mitral valve is narrowed. The valve doesn't open properly, blocking blood flow coming into the left ventricle, the main pumping chamber of the heart. A typical heart is shown on the left.

Mitral valve stenosis — sometimes called mitral stenosis — is a narrowing of the valve between the two left heart chambers. The narrowed valve reduces or blocks blood flow into the lower left heart chamber. The lower left heart chamber is the heart's main pumping chamber. It also is called the left ventricle.

Mitral valve stenosis can make you tired and short of breath. Other symptoms may include irregular heartbeats, dizziness, chest pain or coughing up blood. Some people don't notice symptoms.

Mitral valve stenosis can be caused by a complication of strep throat called rheumatic fever. Rheumatic fever is now rare in the United States.

Treatment for mitral valve stenosis may include medicine or mitral valve repair or replacement surgery. Some people only need regular health checkups. Treatment depends on how severe the valve disease is and whether it's getting worse. Untreated, mitral valve stenosis can lead to serious heart complications.

Symptoms

Mitral valve stenosis usually worsens slowly. You may not have any symptoms, or you may have mild ones for many years. Symptoms of mitral valve stenosis can occur at any age, even during childhood.

Symptoms of mitral valve stenosis include:

- Shortness of breath, especially with activity or when you lie down.

- Fatigue, especially during increased activity.

- Swollen feet or legs.

- Pounding, skipping or otherwise irregular heartbeats, called arrhythmias.

- Dizziness or fainting.

- Fluid buildup in the lungs.

- Chest discomfort or chest pain.

- Coughing up blood.

Mitral valve stenosis symptoms may appear or get worse when the heart rate increases, such as during exercise. Anything that puts stress on the body, including pregnancy or infections, may trigger symptoms.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your healthcare professional right away if you have chest pain, a fast, fluttering or pounding heartbeat, or shortness of breath during activity. Your healthcare professional may tell you to see a doctor trained in heart diseases, called a cardiologist.

If you have been diagnosed with mitral valve stenosis but haven't had symptoms, ask your healthcare team how often to have follow-up exams.

Causes

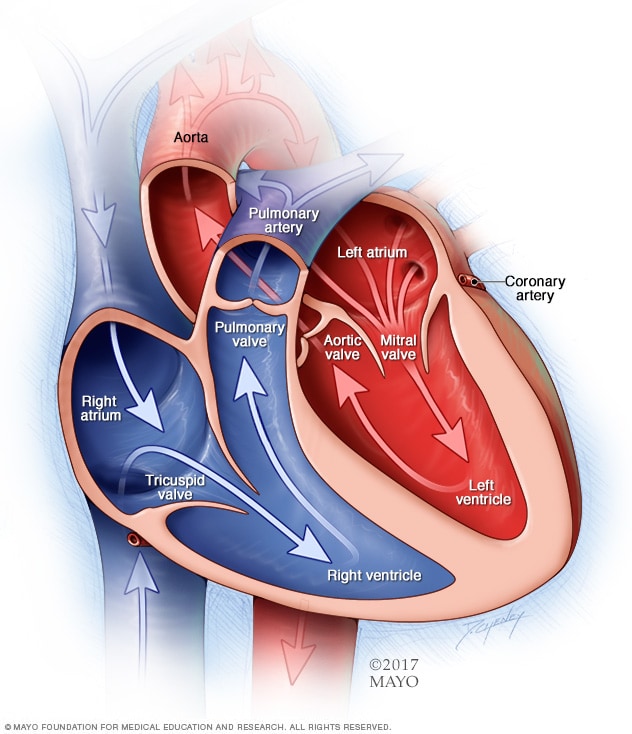

Chambers and valves of the heart

Chambers and valves of the heart

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of the heart. The heart valves are gates at the chamber openings. They keep blood flowing in the right direction.

To understand the causes of mitral valve disease, it may be helpful to know how the heart works.

The mitral valve is one of four valves in the heart that keep blood flowing in the right direction. Each valve has flaps, called leaflets, that open and close once during each heartbeat. If a valve doesn't open or close properly, less blood may flow through the heart to the body.

In mitral valve stenosis, the valve opening narrows. The heart now must work harder to force blood through the smaller valve opening. Blood flow between the upper left and lower left heart chambers may decrease.

Causes of mitral valve stenosis include:

- Rheumatic fever. This complication of strep throat is the most common cause of mitral valve stenosis. When rheumatic fever damages the mitral valve, the condition is called rheumatic mitral valve disease. Symptoms may not be seen until years to decades after rheumatic fever.

- Calcium deposits. As you age, calcium deposits can build up around the mitral valve. This can cause narrowing of the structures that support the mitral valve flaps. The condition is called mitral annular calcification, or MAC for short. Severe MAC can cause mitral stenosis symptoms. It's difficult to treat even with surgery. People with calcium around the mitral valve often have similar problems with the heart's aortic valve.

- Radiation therapy. This is a treatment for certain types of cancer. Radiation to the chest area can sometimes cause the mitral valve to thicken and harden. The heart valve damage typically occurs 20 to 30 years after radiation therapy.

- Heart condition present at birth, called a congenital heart defect. Rarely, some babies are born with a narrowed mitral valve.

- Other health conditions. Lupus and other autoimmune conditions may rarely cause mitral valve stenosis.

Risk factors

Risk factors for mitral valve stenosis include:

- Untreated strep infections. A history of untreated strep throat or rheumatic fever increases the risk of mitral valve stenosis. However, rheumatic fever is rare in the United States. But it's still a problem in developing nations.

- Aging. Older adults are at increased risk of calcium buildup around the mitral valve.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation causes changes in the mitral valve shape and structure. Rarely, people who receive radiation therapy to the chest area for certain types of cancer may develop mitral valve stenosis.

- Illicit drug use. MDMA, short for methylenedioxymethamphetamine and commonly called molly or ecstasy, increases the risk of mitral valve disease.

- Use of certain medicines. Some migraine medicines have an ingredient called ergot alkaloids. Ergotamine (Ergomar) is an example. Ergot alkaloids may rarely cause heart valve scarring that leads to mitral stenosis. Older weight-loss medicines that contained fenfluramine or dexfenfluramine also are linked to heart valve disease and other heart problems. Fen-phen is an example. It's no longer sold in the United States.

Complications

Mitral valve stenosis that is not treated can lead to complications such as:

- Irregular heartbeats. Irregular heartbeats are called arrhythmias. Mitral valve stenosis may cause an irregular and chaotic heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation. It's commonly known as AFib. AFib is a common complication of mitral stenosis. The risk increases with age and more-severe stenosis.

- Blood clots. Irregular heartbeats linked to mitral valve stenosis can cause blood clots to form in the heart. If a blood clot from the heart travels to the brain, a stroke can occur.

- High blood pressure in the lung arteries. The medical name for this condition is pulmonary hypertension. It can happen if a narrowed mitral valve slows or blocks blood flow. Decreased blood flow raises pressure in the lung arteries. The heart must work harder to pump blood through the lungs.

- Right-sided heart failure. Changes in blood flow and high pressure in the lung arteries put a strain on the heart. The heart must work harder to pump blood to the chambers on the right side of the heart. The extra effort eventually causes the heart muscle to become weak and fail.

Prevention

Rheumatic fever is the most common cause of mitral valve stenosis. So the best way to prevent mitral valve stenosis is to prevent rheumatic fever. You can do this by making sure you and your children see a healthcare professional for sore throats. Untreated strep throat infections can develop into rheumatic fever. Strep throat is usually easily treated with antibiotics.

Sept. 04, 2024