Overview

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a heart rhythm disorder that causes fast, chaotic heartbeats. The irregular heartbeats can be life-threatening. LQTS affects the electrical signals that travel through the heart and cause it to beat.

Some people are born with changes in DNA that cause long QT syndrome. This is known as congenital long QT syndrome. LQTS also can happen later in life due to some health conditions, certain medicines or changes in the levels of body minerals. This is called acquired long QT syndrome.

Long QT syndrome can cause sudden fainting and seizures. Young people with LQTS syndrome have a higher risk of sudden cardiac death.

Treatment for long QT syndrome includes lifestyle changes and medicines to prevent dangerous heartbeats. Sometimes a medical device or surgery is needed.

Products & Services

Symptoms

The most common symptom of long QT syndrome is fainting, also called syncope. A fainting spell from LQTS can happen with little to no warning.

Fainting happens when the heart beats in an irregular way for a short time. You might faint when you're excited, angry or scared, or during exercise. If you have LQTS, things that startle you can cause you to pass out, such as a loud ringtone or an alarm clock.

Before fainting happens, some people with long QT syndrome might have symptoms such as:

- Blurred vision.

- Lightheadedness.

- Pounding heartbeats called palpitations.

- Weakness.

Long QT syndrome also can cause seizures in some people.

Babies born with LQTS may have symptoms during the first weeks to months of life. Sometimes the symptoms start later in childhood. Most people born with LQTS have symptoms by age 40. Symptoms of long QT syndrome sometimes happen during sleep.

Some people with long QT syndrome (LQTS) do not notice any symptoms. The disorder may be found during a heart test called an electrocardiogram. Or it may be discovered when genetic tests are done for other reasons.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment for a health checkup if you faint or if you feel like you have a pounding or fast heartbeat.

Tell your healthcare team if you have a parent, brother, sister or child with long QT syndrome. Long QT syndrome can run in families, which means it can be inherited.

Causes

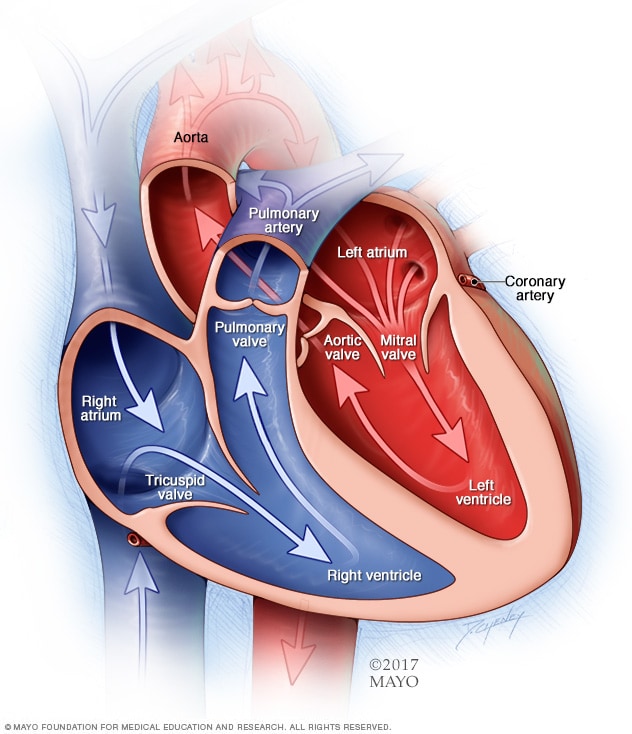

Chambers and valves of the heart

Chambers and valves of the heart

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of the heart. The heart valves are gates at the chamber openings. They keep blood flowing in the right direction.

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is caused by changes in the heart's electrical signaling system. It doesn't affect the shape or form of the heart.

To understand the causes of LQTS, it may help to know how the heart usually beats.

In a typical heart, the heart sends blood out to the body during each heartbeat. The heart's chambers squeeze and relax to pump the blood. The heart's electrical system controls this coordinated action. Electrical signals called impulses move from the top to the bottom of the heart. They tell the heart when to squeeze and beat. After each heartbeat, the system recharges to prepare for the next heartbeat.

But in long QT syndrome, the heart's electrical system takes longer than usual to recover between beats. This delay is called a prolonged QT interval.

Long QT syndrome usually falls into two groups.

- Congenital long QT syndrome. You're born with this type of LQTS. It's caused by changes in DNA that are passed down through families. That means it is inherited.

- Acquired long QT syndrome. This type of LQTS is caused by another health condition or medicine. It usually can be reversed when the specific cause is found and treated.

Causes of congenital long QT syndrome

Many genes and gene changes have been linked to long QT syndrome (LQTS).

There are two types of congenital long QT syndrome:

- Romano-Ward syndrome. This more common type happens in people who get only a single gene change from one parent. Receiving a changed gene from one parent is known as an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.

- Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. This rare form of LQTS usually happens very early in life and is severe. Children with this type of LQTS also are deaf. In this syndrome, children get the gene change from both parents. This is called an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern.

Causes of acquired long QT syndrome

A medicine or other health condition can cause acquired long QT syndrome.

If a medicine causes acquired long QT syndrome, the disorder may be called drug-induced long QT syndrome. More than 100 medicines can cause prolonged QT intervals in otherwise healthy people. Medicines that can cause LQTS include:

- Some antibiotics, such as erythromycin (Eryc, Erythrocin, others), azithromycin (Zithromax) and others.

- Some antifungal medicines used to treat yeast infections.

- Water pills, also called diuretics, that cause the body to remove too much potassium or other minerals.

- Heart rhythm medicines called anti-arrhythmics, which can make the QT interval longer.

- Some medicines used to treat mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression.

- Some medicines used to treat upset stomach.

Always tell your healthcare professional about all the medicines you take, including those you buy without a prescription.

Health conditions that can cause acquired long QT syndrome include:

- Body temperature below 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35 degrees Celsius), a condition called hypothermia.

- Low calcium, also called hypocalcemia.

- Low magnesium, also called hypomagnesemia.

- Low potassium, also called hypokalemia.

- A tumor of the adrenal gland that usually is not cancer, called pheochromocytoma.

- Stroke or brain bleed.

- Underactive thyroid, also called hypothyroidism.

Risk factors

Things that may raise the risk of long QT syndrome (LQTS) include:

- A history of cardiac arrest.

- Having a parent, brother, sister or child with long QT syndrome.

- Using medicines known to cause prolonged QT intervals.

- People who are assigned female at birth who take certain heart medicines.

- A lot of vomiting or diarrhea, which can cause changes in body minerals such as potassium.

- Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, which also cause changes in the levels of body minerals.

If you have long QT syndrome and want to become pregnant, tell your healthcare professional. Your care team carefully checks you during pregnancy to help prevent things that can trigger LQTS symptoms.

Complications

Usually after an episode of long QT syndrome (LQTS), the heart goes back to a regular rhythm. But sudden cardiac death can happen if the heart rhythm isn't quickly corrected. The heart rhythm may reset on its own. Sometimes, treatment is needed to reset the heart rhythm.

Complications of long QT syndrome may include:

-

Torsades de pointes ("twisting of the points"). This is a life-threatening fast heartbeat. The heart's two lower chambers beat fast and out of rhythm. The heart pumps out less blood. The lack of blood to the brain causes sudden fainting, often without warning.

If a long QT interval lasts for a long time, fainting can be followed by a full-body seizure. If the dangerous rhythm does not correct itself, then a life-threatening arrhythmia called ventricular fibrillation follows.

- Ventricular fibrillation. This type of irregular heartbeat causes the lower heart chambers to beat so fast that the heart trembles and stops pumping blood. Unless a device called a defibrillator is quickly used to correct the heart's rhythm, brain damage and death can happen.

- Sudden cardiac death. This is the swift and not expected ending of all heart activity. Long QT syndrome has been linked to sudden cardiac death in young people who otherwise appear healthy. LQTS might be responsible for some unexplained events in children and young adults, such as unexplained fainting, drownings or seizures.

Proper medical treatment and lifestyle changes can help prevent complications of long QT syndrome.

Prevention

There is no known way to prevent congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS). If someone in your family has LQTS, ask a health professional if genetic screening is right for you. With proper treatment, you can manage and prevent the dangerous heartbeats that can lead to LQTS complications.

Regular health checkups and good communication with your healthcare professional also may help prevent causes of some types of acquired long QT syndrome. It's especially important not to take medicines that can affect the heart rhythm and cause a prolonged QT interval.