Overview

Interstitial (in-tur-STISH-ul) lung disease, also called ILD, describes a large group of conditions. Most of these conditions cause inflammation and progressive scarring of lung tissue. As part of this process, lung tissue thickens and stiffens, making it hard for the lungs to expand and fill with air.

At some point, the scarring from interstitial lung disease makes it harder to breathe and get enough oxygen into the bloodstream. Many people with ILD are short of breath with activity and may have a bothersome dry cough.

Interstitial lung disease can have many causes, including long-term exposure to hazardous materials such as asbestos. Some types of autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, also can cause interstitial lung disease. But the cause isn't known sometimes. ILD can have many causes, so treatment varies.

The disease may get worse slowly or rapidly at a pace that often can't be predicted. Once lung scarring occurs, it generally isn't reversible. Treatment focuses on keeping more scarring from occurring, managing symptoms and making quality of life better. Medicines may slow the damage of interstitial lung disease, but many people never fully use their lungs again. Lung transplant is an option for some people who have ILD.

Products & Services

Symptoms

The main symptoms of interstitial lung disease are:

- Shortness of breath at rest or shortness of breath that worsens with physical activity.

- Dry cough.

When to see a doctor

By the time symptoms appear in certain types of interstitial lung disease, lasting lung damage has already occurred. That's why it's important to see your healthcare professional at the first sign of breathing problems. Many conditions other than ILD can affect your lungs. Getting an early and correct diagnosis is important for proper treatment.

Causes

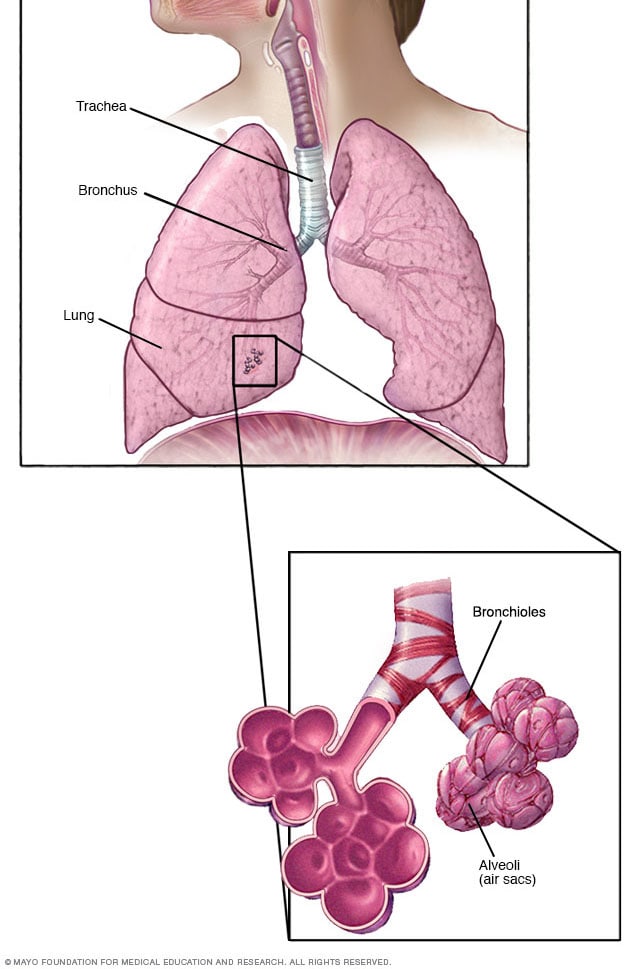

Bronchioles and alveoli in the lungs

Bronchioles and alveoli in the lungs

In your lungs, the main airways, called bronchi, branch off into smaller and smaller passageways. The smallest airways, called bronchioles, lead to tiny air sacs called alveoli.

Interstitial lung disease seems to occur when an injury to your lungs causes a healing response that isn't proper. Ordinarily, your body creates just the right amount of tissue to repair damage. But in ILD, the repair process doesn't work properly. Tissue in and around the lungs' air sacs, called alveoli, becomes inflamed, scarred and thickened. This makes it harder for oxygen to pass into your bloodstream.

There are many types of interstitial lung disease. They're generally grouped by known or unknown causes:

- Your work or the environment.

- An underlying systemic condition.

- Certain types of medicines, or radiation.

- No known cause.

Some interstitial lung diseases can be related to smoking.

Your work or the environment

Long-term exposure to some toxins and pollutants can damage your lungs. For example:

- Pneumoconiosis. Pneumoconiosis (noo-moe-koh-nee-O-sis) refers to a type of interstitial lung disease caused by breathing in certain kinds of dust from work or another environment over a long time. Diseases in this group can cause lung scarring and injury over time, leading to shortness of breath and poor ability to take in oxygen. These symptoms can't be reversed. The disease is often named after the exposure type or work role itself. They include such diseases as coal miner's lung, caused by breathing in coal dust, and asbestosis, caused by breathing in asbestos particles. These diseases also include silicosis, caused by breathing in silica dust.

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. This lung inflammation is caused by breathing in airborne irritants, often involving the proteins of living things. The most common of these airborne irritants are bird protein, mold or bacteria. Conditions of this type also are often named after the type or source of exposure. For example, pigeon-breeder's or bird-lover's disease involves being exposed to bird protein, and farmer's lung involves being exposed to moldy hay. People with this type of lung inflammation can get better by staying away from the irritant. But this type of lung inflammation also can get worse and lead to more-lasting damage if people continue to breathe in the irritant.

Underlying systemic condition

Certain diseases or conditions may lead to interstitial lung disease. For example:

- Connective tissue diseases. These include autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma and mixed connective tissue disease. These diseases result in an immune response that isn't proper and may cause tissue inflammation and scarring in the body, including in the lungs.

- Sarcoidosis. This is a disease that includes the growth of tiny collections of inflammatory cells called granulomas in any part of your body — most commonly the lungs and lymph nodes. Other commonly affected organs include the eyes, skin, heart, spleen and liver.

Medications, radiation

Certain types of medicines can cause interstitial lung disease in some people. This may or may not be reversible based on the type and length of exposure.

Medicines more commonly associated with ILD are:

- Chemotherapy drugs. Drugs designed to kill cancer cells, such as bleomycin, gemcitabine and immune checkpoint inhibitors, can damage lung tissue.

- Heart medicines. Some drugs used to treat irregular heartbeats, such as amiodarone (Nexterone, Pacerone), may harm lung tissue.

- Some antibiotics. Nitrofurantoin (Macrobid, Macrodantin, others) and daptomycin can cause lung damage.

- Anti-inflammatory drugs. Certain anti-inflammatory drugs, such as methotrexate (Trexall, Xatmep, others) or sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), can damage the lungs.

Radiation directed at the chest during treatments for certain types of cancers — breast and lung cancers, for example — may lead to injury or long-term scarring in some people. How severe the damage is may depend on:

- How much of the lung was exposed to radiation.

- The total amount of radiation given.

- Whether chemotherapy also was used.

- Whether there is underlying lung disease.

No known cause

The list of substances and conditions that can lead to interstitial lung disease is long. Even so, in some people, the cause is never found. Conditions without a known cause are grouped together under the label of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. For example:

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, also called IPF. IPF is a typically progressive lung disease that occurs when lung tissue becomes damaged and scarred — what's known as fibrosis. Idiopathic means the cause isn't known. IPF can be seen on imaging and biopsy if a lung biopsy is taken. This thickened, stiff tissue makes it harder for your lungs to work properly. The most common type of ILD, IPF often gets worse and can't be reversed.

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, also called COP. COP is a rare lung condition in which the small airways, called bronchioles, and tiny air-exchange sacs, called alveoli, get inflamed. This inflammation makes it hard to breathe. Imaging tests show pneumonia, but COP is not an infection, and the cause is not known. Scarring or fibrosis is rare, but it can happen in some patients if the condition comes back.

- Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. This type of interstitial lung disease causes cells to be inflamed or scar tissue to build up in the spaces between the air sacs in the lungs. It's more likely to happen in people with connective tissue diseases, but it also can be linked to other conditions.

Risk factors

Factors that may make you more likely to get interstitial lung disease include:

- Age. ILD is much more likely to affect adults, although babies and children sometimes get the disease.

- Exposure to toxins at work or in the environment. Working in mining, farming or construction, or for any reason getting exposed to pollutants known to damage lungs, raises your risk of getting ILD.

- Smoking. Some forms of ILD are more likely to occur in people with a history of smoking. Active smoking may make the condition worse, especially if you also have emphysema.

- Radiation and chemotherapy. Having radiation treatments to your chest or using certain chemotherapy drugs raises your risk of lung disease.

- Connective tissue disease. This includes autoimmune diseases that can raise your risk of ILD.

Complications

Interstitial lung disease can lead to a series of life-threatening complications, including:

- High blood pressure in your lungs, also known as pulmonary hypertension. Unlike systemic high blood pressure, this condition affects only the arteries in your lungs. Scar tissue or low oxygen levels restrict the smallest blood vessels, limiting blood flow in your lungs. This raises pressure within the pulmonary arteries and can worsen oxygen exchange, lowering oxygen levels in your blood. Pulmonary hypertension is a serious illness that may get worse over time, causing the right side of your heart to fail.

- Right-sided heart failure, also known as cor pulmonale. This serious condition occurs when your heart's lower right chamber, also known as the right ventricle, must pump harder than usual to move blood through blocked pulmonary arteries. Eventually, the right ventricle fails from the extra strain. This is often due to pulmonary hypertension.

- Respiratory failure. In the end stage of chronic ILD, respiratory failure occurs when severely low blood oxygen levels, along with rising pressures in the pulmonary arteries and the right ventricle, cause the heart to fail.

Prevention

To prevent interstitial lung disease, avoid exposure to toxins at work, such as asbestos, coal dust and silica dust. Also, avoid exposure to toxins in the environment, such as bird protein, mold and bacteria. If you must be around these toxins, protect yourself by wearing a respirator. Other ways to prevent ILD include not smoking and avoiding secondhand smoke.

If you have an autoimmune disease or are taking medicines that raise your risk of getting ILD, talk with your healthcare professional about steps you can take to prevent ILD. Also, get vaccinated because respiratory infections can make symptoms of ILD worse. Be sure you get the pneumonia vaccine and a flu shot each year. Also, ask your healthcare professional about getting vaccinated for pertussis, COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus, also called RSV.

Nov. 23, 2024