Diagnosis

Inflammatory bowel disease FAQs

Gastroenterologist William Faubion, M.D., answers the most frequently asked questions about inflammatory bowel disease.

{Music playing}

How much will IBD affect me?

William A. Faubion, Jr., M.D., Gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic: I think most simply, it depends on where in the bowel the disease is affecting and how severe your case is. Every practitioner will tell you that in an ideal world, it shouldn't affect your life at all. It's been well studied that actually inflammatory bowel disease does not significantly change the overall lifespan of the patients. But what we really care about is quality of life. I think for the vast majority of patients that we see, the appropriate medical plan can keep patients generally free of symptoms over the order of one to three years. So I think the biggest ways that the disease is going to affect your life is perhaps you may need to watch a bit what you eat. You'll need to keep in touch with your treatment team and you'll need to take medications as they've been prescribed. But if you do those three things, I think that most practitioners would tell you, we'd rather you not be thinking about your inflammatory bowel disease. Let us worry about that.

Why do people get IBD?

Most of us that are involved in the research of this condition would suggest that there's three major causes that we study for this condition. The first would be the environment. Most of us believe that there's some environmental insult that leads to the chronic inflammation in the intestine. That environmental insult may be dietary. It may be a particular bug that lives in the bowel, or may be a function of that bug, which is also a function of the diet. The second most important thing is having the right genes. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease is complicated and actually quite widespread. So most people have the right genetic makeup for this disease but don't actually develop the disease. And then the third component is these two things impact on the immune system. And the immune system is what is actually causing the chronic inflammation that's present in the intestine that we prescribe medications to treat.

Can IBD affect my lifespan?

The short answer is no, it will not. There's multiple lines of research that when patients with inflammatory bowel disease are controlled against patients their same age, with their same medical problems, without inflammatory bowel disease, achieve roughly the same lifespan.

Does my diet affect IBD?

If one has a narrowing in the small bowel related to Crohn's disease, something called a stricture, diet becomes very important because if certain patients eat foods that have too much roughage or fiber, then those types of foods can cause an impaction or block the narrowing in the small bowel, leading to signs and symptoms of something we call an obstruction: Belly pain, vomiting, loud noises in the bowel. Another way diet can impact the disease is if you have damage of the small bowel, that can impact your ability to do certain types of functions in the small bowel -- like absorbing dairy products, for example.

Is there any cancer risk from having IBD?

The main risk factor for cancer would be colorectal or cancer of the large bowel. And that comes, we believe, from the chronic inflammation of the colon. That's why it's a good idea to maintain close contact with your treatment team. And that's why we recommend routine colonoscopies, passing the scope up into the colon, looking for those early changes associated with cancer.

What's the risk of passing IBD to my children?

That's a very common and valid concern amongst parents that come for evaluation for their inflammatory bowel disease. Generally the risk is slightly higher for Crohn's disease than ulcerative colitis. But that being said, you're still far more likely to be the only member of your family with this condition, than have a familial what we call penetrance.

Are stool transplants real?

The short answer is yes. This science was actually developed for an infection rather than inflammatory bowel disease. The science has been developed over a period of about 15 years. And it really has come to age with an infection called clostridium difficile or C. diff. Stool transplants now are actually a very common tool to treat recurrent or refractory infection with this C. diff species. Because of the excitement in the infectious disease field or the C. diff field, there are numerous trials that are running in inflammatory bowel disease.

How can I be the best partner to my medical team?

So I think just showing up is the first thing that you can do. We always consider this as a partnership between the patient and the provider. There's a lot to consider when we talk about the medications for inflammatory bowel disease. Some of those medications have risk factors. So those discussions are important, can be complex and can be time-consuming. So showing up, being present, participating in those conversations, and being educated yourself. There are a lot of resources out there to investigate what the risks and benefits to a variety of different strategies might be. Communicating well with your team and again, just being there and showing up.

{Music playing}

To help confirm a diagnosis of IBD, a healthcare professional generally recommends a combination of tests and procedures:

Lab tests

-

Blood tests. Blood tests can check for signs of infection or anemia — a condition in which there aren't enough red blood cells to carry oxygen to the tissues.

These tests also may be used to check for levels of inflammation, liver function or the presence of infections that aren't active, such as tuberculosis. Blood also may be screened for the presence of immunity against infections.

- Stool studies. A stool sample may be used to test for blood or organisms, such as infection-causing bacteria or, rarely, parasites, in the stool. These can be causes of diarrhea and symptoms. Sometimes looking for stool markers of inflammation, such as calprotectin, can be helpful.

Endoscopic procedures

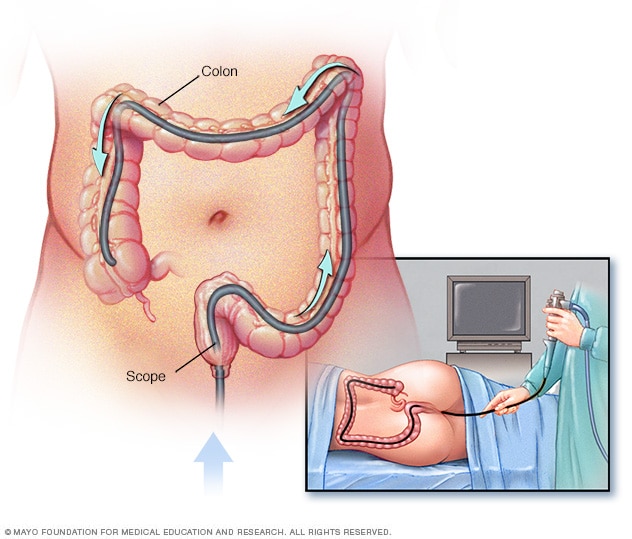

Colonoscopy exam

Colonoscopy exam

During a colonoscopy, a healthcare professional puts a colonoscope into the rectum to check the entire colon.

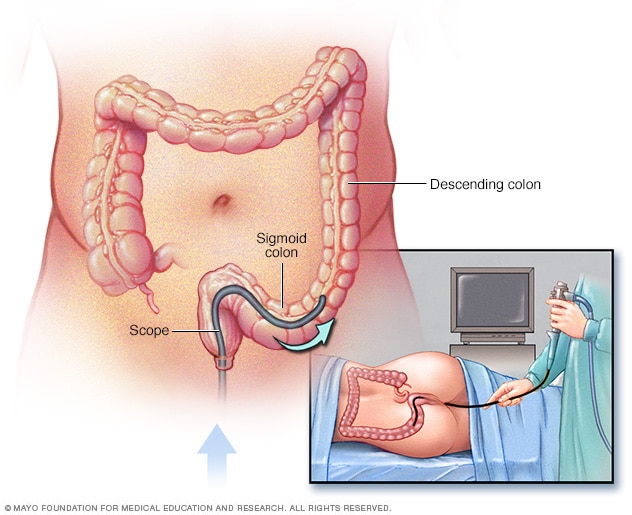

Sigmoidoscopy exam

Sigmoidoscopy exam

During a flexible sigmoidoscopy exam, the healthcare professional puts a sigmoidoscope into the rectum to check the lower colon.

- Colonoscopy. This exam allows a view of the entire colon and parts of the small intestine by using a thin, flexible, lighted tube with a camera at the end. During the procedure, a small sample of tissue called a biopsy may be taken for analysis. A biopsy is the way to make the diagnosis of IBD versus other forms of inflammation.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy. This exam uses a slender, flexible, lighted tube to examine the rectum and sigmoid, the last portion of the colon. If the colon is badly inflamed, this test may be done instead of a full colonoscopy.

- Upper endoscopy. In this procedure, a slender, flexible, lighted tube is used to examine the esophagus, stomach and first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum. While it is rare for these areas to be involved with Crohn's disease, this test may be recommended if you are having nausea and vomiting, difficulty eating, or upper abdominal pain.

- Capsule endoscopy. This test is sometimes used to help diagnose Crohn's disease involving the small intestine. You swallow a capsule that has a camera in it. The images are transmitted to a recorder you wear on your belt, after which the capsule exits your body painlessly in your stool. You may still need an endoscopy with a biopsy to confirm a diagnosis of Crohn's disease. Capsule endoscopy should not be done if a bowel obstruction is suspected.

- Balloon-assisted enteroscopy. For this test, a scope is used in conjunction with a device called an overtube. This lets the technician look further into the small bowel where standard endoscopes don't reach. This technique is useful when results of a capsule endoscopy aren't as expected but the diagnosis is still in question.

Imaging tests

- X-ray. If you have severe symptoms, your provider may use a standard X-ray of your abdominal area to rule out serious complications, such as toxic megacolon or a perforated colon.

- Computerized tomography, also called CT. You may have a CT scan — a special X-ray technique that provides more detail than a standard X-ray does. This test looks at the entire bowel as well as tissues outside the bowel. CT enterography is a special CT scan that provides better images of the small bowel. This test has replaced barium X-rays in most medical centers.

- Magnetic resonance imaging, also called MRI. An MRI scanner uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create detailed images of organs and tissues. An MRI is particularly useful for evaluating a fistula around the anal area or the small intestine, a test called MR enterography. Unlike with CT, there is no radiation exposure with MRI.

More Information

Treatment

The goal of inflammatory bowel disease treatment is to reduce the inflammation that triggers symptoms. In the best cases, this may lead not only to symptom relief but also to long-term remission and reduced risk of complications. IBD treatment usually involves either medicines or surgery.

Anti-inflammatory medicines

Anti-inflammatory medicines are often the first step in the treatment of ulcerative colitis, typically for mild to moderate disease. Anti-inflammatories include aminosalicylates, such as mesalamine (Delzicol, Rowasa, others), balsalazide (Colazal) and olsalazine (Dipentum).

Time-limited courses of corticosteroids also are used to induce remission. In addition to being anti-inflammatory, steroids are immunosuppressing. The type of medicine recommended depends on the area of the colon that's affected.

Immunomodulators

These drugs work in a variety of ways to suppress the immune response that releases inflammation-inducing chemicals into the body. When released, these chemicals can damage the lining of the digestive tract.

Some examples of immunosuppressant drugs include azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran), mercaptopurine (Purinethol, Purixan) and methotrexate (Trexall).

Small molecules

More recently, medicines given by mouth that are known as small molecules have become available for IBD treatment. Janus kinase inhibitors, also called JAK inhibitors, are a type of small molecule medicine that helps reduce inflammation by targeting parts of the immune system that cause inflammation in the intestines. Some JAK inhibitors for IBD include tofacitinib (Xeljanz) and upadacitinib (Rinvoq).

Ozanimod (Zeposia) is another type of small molecule medicine available for IBD. Ozanimod is a medicine known as a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator, also called an S1P receptor modulator.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, also called the FDA, recently issued a warning about tofacitinib, stating that preliminary studies show an increased risk of serious heart-related conditions and cancer from taking this medicine. If you're taking tofacitinib for ulcerative colitis, don't stop taking the medicine without first talking with a healthcare professional.

Biologics

Biologics are a newer category of therapy in which treatment is directed toward neutralizing proteins in the body that are causing inflammation. Some of these medicines are administered via intravenous, also called IV, infusions and others are injections you give yourself. Examples include infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), golimumab (Simponi), certolizumab (Cimzia), vedolizumab (Entyvio), ustekinumab (Stelara) and risankizumab (Skyrizi).

Antibiotics

Antibiotics may be used with other medications or when infection is a concern — if there is perianal Crohn's disease, for example. Often-prescribed antibiotics include ciprofloxacin (Cipro) and metronidazole (Flagyl).

Other medicines and supplements

In addition to managing inflammation, some medicines may help relieve symptoms. But always talk to a healthcare professional before taking any nonprescription medicines. Depending on how bad your IBD is, one or more of the following may be recommended:

-

Antidiarrheals. A fiber supplement — such as psyllium (Metamucil) or methylcellulose (Citrucel) — can help relieve mild to moderate diarrhea by adding bulk to the stool. For more-severe diarrhea, loperamide (Imodium A-D) may be effective.

These medicines and supplements could be harmful or not effective in some people with strictures or certain infections. Consult your healthcare team before starting these treatments.

- Pain relievers. For mild pain, acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) may be recommended. However, medicines called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve) and diclofenac sodium, likely will make symptoms worse and can make the disease worse as well.

- Vitamins and supplements. If you're not absorbing enough nutrients, vitamins and nutritional supplements may be recommended.

Nutritional support

If weight loss is significant, a healthcare professional may recommend a special diet given via a feeding tube, called enteral nutrition, or nutrients injected into a vein, called parenteral nutrition. Nutritional support can improve your overall nutrition and allow the bowel to rest. Bowel rest can reduce inflammation in the short term.

If you have stenosis or stricture in the bowel, your care team may recommend a low-residue diet. This diet can help minimize the chance that undigested food will get stuck in the narrowed part of the bowel and lead to a blockage.

Surgery

If diet and lifestyle changes, drug therapy, or other treatments don't relieve your IBD symptoms, surgery may be recommended.

-

Surgery for ulcerative colitis. Surgery involves removal of the entire colon and rectum. An internal pouch is then made and attached to the anus. This allows the passing of stool without having a bag for stool on the outside of the body.

In some people, creating an internal pouch is not possible. Instead, surgeons create a permanent opening in the abdomen, called an ileal stoma, through which stool passes for collection in an attached bag.

-

Surgery for Crohn's disease. Up to two-thirds of people with Crohn's disease require at least one surgery in their lifetimes. However, surgery does not cure Crohn's disease.

During surgery, the surgeon removes a damaged part of the digestive tract and then reconnects the healthy sections. Surgery also may be used to close fistulas and drain abscesses.

The benefits of surgery for Crohn's disease are usually temporary. The disease recurs in many people, often near the reconnected tissue. The best approach is to follow surgery with medicine to lessen the risk of recurrence.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Sometimes you may feel helpless when facing inflammatory bowel disease. But changes in your diet and lifestyle may help manage your symptoms and lengthen the time between flare-ups.

Diet

There's no firm evidence that what you eat causes inflammatory bowel disease. But some foods and beverages can make symptoms worse, especially during a flare-up.

You might find it helpful to keep a food diary to track what you're eating, as well as how you feel. If you discover that some foods are causing your symptoms to flare, you can try eliminating those foods.

Here are some general dietary suggestions that may help you manage your condition:

- Limit dairy products. Many people with inflammatory bowel disease find that problems such as diarrhea, belly pain and gas improve by limiting or not using dairy products. You may be lactose intolerant — that is, your body can't digest the milk sugar, called lactose, in dairy foods. Using an enzyme product such as Lactaid may help as well.

- Eat small meals. You may find that you feel better eating five or six small meals a day rather than two or three larger ones.

- Drink plenty of liquids. Try to drink plenty of liquids daily. Water is best. Alcohol and beverages that contain caffeine stimulate your intestines and can make diarrhea worse, while carbonated drinks frequently produce gas.

- Consider multivitamins. Because Crohn's disease can interfere with your ability to absorb nutrients and because your diet may be limited, multivitamin and mineral supplements are often helpful. Check with your healthcare team before taking any vitamins or supplements.

- Talk with a dietitian. If you begin to lose weight or your diet has become very limited, talk with a registered dietitian.

Smoking

Smoking increases your risk of having Crohn's disease, and once you have it, smoking can make it worse. People with Crohn's disease who smoke are more likely to have relapses and need medicines and repeat surgeries.

Smoking may help prevent ulcerative colitis. However, its harm to overall health outweighs any benefit, and quitting smoking can improve the general health of your digestive tract, as well as provide many other health benefits.

Stress

The association of stress with Crohn's disease is controversial, but many people who have the disease report symptom flares during high-stress periods. If you have trouble managing stress, try one of these strategies:

- Exercise. Even mild exercise can help reduce stress, relieve depression and adjust bowel function . Talk with your doctor or other healthcare professional about an exercise plan that's right for you.

- Biofeedback. This stress-reduction technique may train you to reduce muscle tension and slow your heart rate with the help of a feedback machine. The goal is to help you enter a relaxed state so that you can cope more easily with stress.

- Regular relaxation and breathing exercises. One way to cope with stress is to regularly relax and use techniques such as deep, slow breathing to help you feel calm.

Alternative medicine

Many people with digestive disorders have used some form of complementary and alternative medicine. However, there are few well-designed studies of the safety and effectiveness of these treatments.

Researchers suspect that adding more of the beneficial bacteria that are typically found in the digestive tract might help combat IBD. These bacteria are called probiotics. Although research is limited, there is some evidence that adding probiotics along with taking medicines may be helpful.

Coping and support

IBD doesn't just affect you physically — it takes an emotional toll as well. If signs and symptoms are severe, your life may revolve around a constant need to run to the toilet. Even if your symptoms are mild, you may find it difficult to be out in public. All of these factors can alter your life and may lead to depression. Here are some things you can do:

- Be informed. One of the best ways to better manage your IBD is to find out as much as possible about inflammatory bowel disease. Look for information from reputable sources such as the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation.

- Join a support group. Although support groups aren't for everyone, they can provide valuable information about your condition as well as emotional support. Group members frequently know about the latest medical treatments or integrative therapies. You may also find it reassuring to be among others with IBD.

- Talk with a therapist. Some people find it helpful to consult a mental health professional who's familiar with inflammatory bowel disease and the emotional difficulties it can cause.

Although you may feel discouraged about living with IBD, research is ongoing, and the outlook is improving.

Preparing for your appointment

Symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease may first prompt a visit to your main healthcare team. However, you may then be referred to a professional who specializes in treating digestive disorders, called a gastroenterologist.

Because appointments can be brief, and there's often a lot of information to discuss, it's a good idea to be well prepared. Here's some information to help you get ready and what to expect at your visit.

What you can do

- Find out how to prepare for your appointment. At the time you make the appointment, be sure to ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet.

- Write down any symptoms you're experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you made the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medications, including nonprescription medicines and any vitamins or supplements that you're taking.

- Take a family member or friend along. Sometimes it can be difficult to remember everything during an appointment. Someone who goes with you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask during your appointment.

Preparing a list of questions beforehand may help you make the most of your visit. List your questions from most important to least important in case time runs out. For inflammatory bowel disease, some basic questions to ask include:

- What's causing these symptoms?

- Are there other possible causes for my symptoms?

- What kinds of tests do I need? Do these tests require any special preparation?

- Is this condition temporary or long lasting?

- What treatments are available, and which do you recommend?

- Are there any medicines that I should avoid?

- What types of side effects can I expect from treatment?

- What sort of follow-up care do I need? How often do I need a colonoscopy?

- Are there any alternatives to the primary approach that you're suggesting?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Do I need to change my diet?

- Is there a generic alternative to the medicine you're prescribing?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

- Is there a risk to me or my child if I become pregnant?

- Is there a risk of complications in my partner's pregnancy if I have IBD and start the pregnancy?

- What is the risk of my child having IBD if I have it?

- Are there support groups for people with IBD and their families?

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare team is likely to ask you a number of questions. Being ready to answer them may reserve time to go over points you want to spend more time on. You may be asked:

- When did you first begin experiencing symptoms?

- Have you have symptoms all the time or do they come and go?

- How bad are your symptoms?

- Do you have belly pain?

- Have you had diarrhea? How often?

- Do you awaken from sleep during the night because of diarrhea?

- Is anyone else in your home sick with diarrhea?

- Have you lost weight without trying to?

- Have you ever had liver problems, hepatitis or jaundice?

- Have you had problems with your joints, eyes or skin — including rashes and sores — or had sores in your mouth?

- Do you have a family history of inflammatory bowel disease?

- Do your symptoms affect your ability to work or do other activities?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- Is there anything that you've noticed that makes your symptoms worse?

- Do you smoke?

- Do you take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines, for example, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve) or diclofenac sodium? These medicines also are called NSAIDs.

- Have you recently taken antibiotics?

- Have you recently traveled? If so, where?

Dec. 18, 2024